| Van de Veldt is a jewish name ,,,,,Jewess Author

|

|

|

Theodor Hendrik van de Velde - Dutch Jew (1873-1937) A Dutch physician. He is the author of the revolutionary sex manual Perfect Marriage. Velde broke away from the moralizing duscussion of the standard missionary position and sexual behavior in general. He described 10 different positions for intercourse and dared to advocate the 'genital kiss' as an acceptable part of foreplay. |

|

|

|

|

|

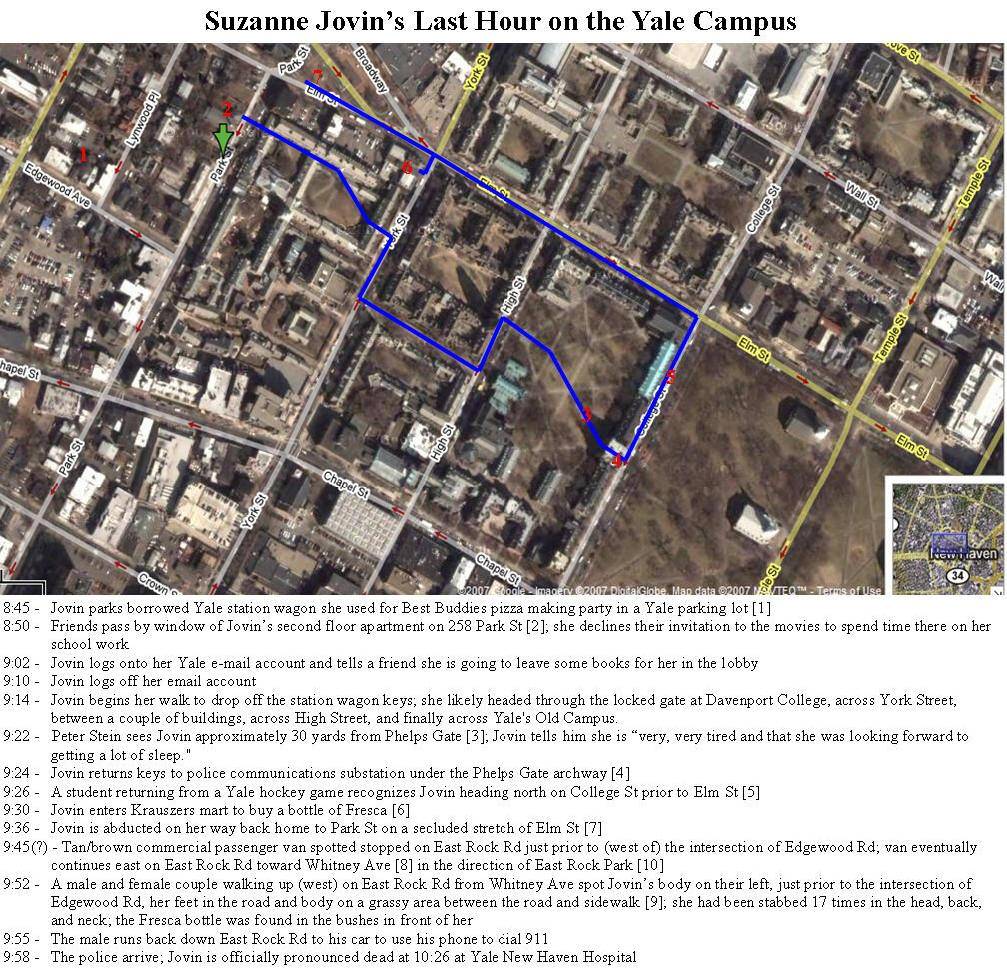

In his August 2007 letter to Chief State’s Attorney Kevin Kane,

Van de Velde attached the following list of suggestions for investigators

to consider:

AVENUES TO INVESTIGATE IN THE

SUZANNE JOVIN COLD CASE HOMICIDE

Crime Date: December 4, 1998, approximately 9:45 pm

Jovin found at the corner of East Rock and Edgehill Roads,

New Haven, Connecticut bleeding from multiple stab wounds

1) The Fresca soda bottle found at the

crime scene had on it two fingerprints: Jovin’s and that of a

not-yet-identified person. If the bottle is still available (i.e., if the New

Haven police did not destroy the evidence or allow the fingerprint to degrade),

the DNA of the second

print should be discerned and compared to the DNA found under the victim’s

fingernails. If there is a match, the likelihood that this is the killer’s DNA

is enormous. The only chance of innocent contact would be if the convenience

store clerk who stocked the Fresca also happened to be at the cashier’s station

when Jovin visited and somehow had his palm scratched by Jovin when retrieving

change. Other than that extremely unlikely scenario, if the DNA under the

fingernails and on the soda bottle match, the DNA belongs to the perpetrator.

2) Since several witnesses report seeing a suspicious van parked at the crime

scene at the time of the crime, investigators should compare the circumstances

of Jovin’s death to deadly or potentially deadly abductions known to have been

carried out in by Connecticut men driving vans. Notice should be taken of John

F. Regan and William Devlin Howell, both of whom used vans in their abductions.

If the Jovin crime scene DNA (bottle and/or fingernail) has not been compared to

the DNA of each of these criminals, it should be. Regan, of course, is the

Waterbury family man who was much in the news in 2005-6 because of the latest of

his sexual assaults: using his van in a failed attempt in Saratoga Springs, NY

to abduct a 17-year-old high school female athlete. Regan subsequently pled

guilty and was sentenced in July 2006 to 12 years in New York prisons for the

attempted kidnapping. Earlier, at Governor Rell’s November 21, 2005, press

conference trumpeting the value of Connecticut’s DNA

Data Base, Henry Lee described how DNA evidence had broken open an

11-year-old case about a woman kidnapped and raped by John Regan in 1993. Howell

is the Connecticut man now at the top of the Cold Case Unit’s website listing of

solved cases. On January 30, 2006, he pled guilty to the July 2003 abduction and

murder of Nilsa Arizmendi of Wethersfield. It was the victim’s blood found in

his van—by North Carolina police on a Connecticut warrant—that led to his

arrest. Additional blood was discovered in his van and was never identified, as

the Connecticut Cold Case Unit’s very own website makes clear. The State, in

fact, appealed to the public for help to discover whose blood was in Howell’s

van.

3) The crime-scene DNA and the DNA for Regan and Howell should be compared to

all possible CODIS names in Connecticut and elsewhere.

4) The tip of the knife used in the

Jovin attack was broken off and lodged inside Jovin’s head. The metallurgy of

the knife tip should be discerned and traced to a manufacturer. If a

manufacturer can be identified, perhaps the type of knife can be too.

5) A microscopic forensic analysis should be conducted on Jovin's

sweatshirt--reported covered with blood—to determine molecular trace elements

deposited on Jovin's clothing. Such an analysis could identify dirt and tire

molecules, among other unique substances, which can be traced to a specific

region or vehicle. A microscopic forensic test might show whether Jovin's

clothing was in contact with the floor of a Dodge B250 van, the type the New

Haven police said was seen at the crime scene, or of some other van.

6) The DNA found under Jovin’s fingernail and the DNA discerned from the

fingerprint on the soda bottle found at the crime scene should be entered into

the Connecticut and Combined DNA Index System (CODIS) and periodically compared

with the samples entered not only in CT but in the other states.

7) The DNA in the blood under Jovin’s fingernails had a rare or unusual marker.

That might allow the DNA to be compared more easily than would otherwise be the

case, by limiting the comparison to samples that have that marker. Furthermore,

that unusual marker should be made public, in the hopes that the public could

help identify suspects.

8) Determine the age of the individual through testing the hormones left within

the fingerprints found on the Fresca soda bottle found at the crime scene. (The

State’s forensics lab could perform this test.)

9) Conduct a sweat print analysis on the clothing. Dale Perry of the Lawrence

Berkeley National Laboratory in California can do one as small as 10 micrometers

across - smaller than a single fingerprint ridge. He uses a synchrotron, a

particle accelerator to produce intense light that, when shone at the sample, is

absorbed and reveals a chemical makeup that may be unique. If not unique to a

person, it can at least segregate age and sex. This technique requires very

little sample.

10) Determine the ethnicity of the individual through analysis of the DNA found

under the fingernails of Jovin. Any result could be potentially helpful.

Consider the possibility that the individual is Indo-European, Asian or African.

Then match the ethnicity with the age of the individual, and one has a new lead.

11) Perform a microscopic forensic analysis to determine molecular trace

elements deposited on Jovin's clothing, which could identify dirt and tire

molecules, among other unique substances, which can be traced to a specific

region or vehicle. A microscopic forensic test might show whether Jovin's

clothing was in contact with the floor of a Dodge B250 van, the type police said

was seen at the crime scene, or of some other van. Skip Palenik in Chicago, for

instance, could perform such analysis (see: www.microtracescientific.com/).

12) The NHPD failed to investigate or even interview some of the more likely

individuals associated with the last event Jovin attended: the party at the Best

Buddies (Special Adult) program in New Haven the very evening of her death. The

director of that Program, Ms. Dawn DeFeo, claims only a few individuals from her

organization were interviewed regarding the crime and none, as far as she knows,

was asked to provide a DNA sample. Yet one of the individuals of the program was

no longer included in the program in part because of a complaint filed by Jovin

concerning his treatment of a Program member. That individual had an ‘anger

management’ problem and perhaps had access to Marrakech Program vans which were

used to transport program members. Some relevant facts, according to DeFeo:

• Jovin was upset with the Program (named Marrakech; she had complained about

the staff assistant in particular).

• There was a fire in her buddy’s apartment that she believed was caused by the

assistant's negligence. The assistant allowed her Buddy to operate the stove in

the apartment, which he wasn't supposed to do, and the result was a fire.

• The staff assistant did other things she thought inappropriate.

• He was subsequently moved to a position that could be regarded as a demotion.

• He had an "anger management issue" problem.

• The individual has not been asked for a fingerprint or DNA sample.

In addition, regardless of how many of these suggestions are explored, the

unsolved Jovin slaying should be posted--as soon as possible--as a current cold

case (with the exceptional $150,000 reward noted) on the Chief State's

Attorney's website.

Respectfully,

James Van de Velde, August 7, 2007

Re: 4/1/01 - Hartford Courant: Are You Wrong About James Van de Velde? (Part 1

of 4)

Are You Wrong About James Van de Velde?

Story by LES GURA

The Hartford Courant

April 1, 2001

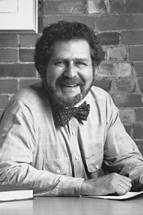

[picture]

James Van de Velde believes the police never properly investigated the Suzanne

Jovin slaying, that Yale University improperly removed him from teaching and

that the media perpetuated the image of guilt the police and Yale created. Now

working for the Department of Defense, Van de Velde was photographed by Tom

Brown in Washington, D.C.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The bright red type signifying a new Lotus Notes message popped up late in the

morning on Sept. 19, 2000.

"James Van de Velde."

I stared at it. Why would the former Yale University lecturer and only named

suspect in New Haven's most notorious

unsolved murder, the Dec. 4, 1998, stabbing death of 21-year-old Yale

senior Suzanne Jovin, be e-mailing me?

True, I had a connection with Van de Velde; he had been a student in the

graduate journalism course I'd taught at Quinnipiac College that fall. But I

hadn't seen or spoken to him since Dec. 7, 1998, 36 hours before his name was to

become publicly linked with Jovin's. When The Courant, where I am city editor,

sought insight into the case in early 1999 and asked me to reach out to Van de

Velde, he never answered my message. So why now?

I showed a couple of colleagues the e-mail message with the infamous name, still

unopened in my message folder. Eyebrows were raised, smart-aleck remarks ("So,

the killer wants to talk with you, huh?") prevailed. Van de Velde's messaging me

had good titillation value in a cynical newsroom whose collective gavel had long

ago, like that of most people who had ever heard about the case, banged down on

the guilty side.

The e-mail got me to thinking about Van de Velde and the other seven students

who comprised MC 504A, Newsroom Clinical. They were curious, intelligent and

driven by a desire to succeed. Everyone had done well in the class, with three

going on in newspapers. There was the doctor who loved to write op-ed pieces

about our problem-plagued health-care system but who longed to improve his

prose. There was a television producer, and two people in public relations; they

would each go on to find new jobs in the two years that came and went. And there

was Van de Velde, whose future would change so dramatically the day after our

final session, our goodbye dinner the night of Monday, Dec. 7.

I had started the class that night in the regular setting, the computer room

inside Quinnipiac's communications building, set in the shadow of Sleeping Giant

State Park in Hamden. One last time we sat around the oval desk, and I gave them

my final speech, to strive always for the best, to work hard and to remember the

three questions they should ask themselves before writing: What's the story,

what's the significance of the story, and what's my point? The latter question

deals not with personal viewpoint so much as the ability to understand the

motivation for writing a story. In short, it is an admonition to think.

After class, we departed in separate cars for Dickerman's, a quiet restaurant

and bar five minutes away. There, we reassembled around a long, rectangular

table. At one end was Van de

Velde,

flanked by me and Zoe

Stetson, Carla Yarbrough on Stetson's other side. That was how the

conversation divided that night: the four of us, and everyone else.

Yarbrough, then a producer at WTNH, Channel 8, asked Van de Velde if he knew the

student who had been slain the previous Friday night. Yes, he told her. In fact,

she was in one of his seminars, and he had been her senior essay advisor. She

was an excellent student, he said. In class, I had found Van de Velde a calm

man, who spoke quietly but with authority when he chose to. That night, he kept

his voice under control, but words came haltingly, his face betraying emotions

he was struggling to control. He said that earlier that day had been the last

meeting of his class, and it had been tearful and difficult for his students.

Later, I would review over and over the words and meaning of that night at

Dickerman's. I always came away thinking Van de Velde's was exactly the reaction

I would have had, if something similar had happened to one of my students.

The Sept. 19 e-mail from Van de Velde cut right to the chase. "The Jovin case

has been an intelligence test for the Connecticut media, which it has profoundly

failed: can the New Haven Police and Yale name `anyone' a suspect in a crime and

the media obligingly massacre the person in public with no regard to the facts,

accountability or ethics. The answer to date is a resounding yes."

So began my more than two-month e-mail dance with Van de Velde, he lobbing

brickbats even as he enlisted my help in writing about the Jovin case and his

status as one in a "pool of suspects" cited by police and Yale University.

Sept. 21: "Frankly, I am checking you out, not the other way around. ... I have

never had anything to fear except shoddy journalism and corrupt cops. Once you

hear the story, you will have many phone calls to make to certain people to

corroborate the facts. If you are smart, you will understand why certain people

will refuse to talk with you. And then you will be faced with your true test:

will you have the personal strength to write what you believe based on my story

and your intuition, or will you fall apart and degenerate into rumor repeating

and `It's still possible he did it since he says he was home watching television

alone.'"

Oct. 5: "The way I see it is this: my life is destroyed yet there is nothing I

have ever done that I feel ashamed of. You can't take away my dignity. Yet yours

is gone; you just don't see it. The fact that you tolerate the state `naming'

and destroying people based on speculation is an embarrassment for you, not me.

"Why does the moronic media ask the New Haven Police blandly `So what is new in

the Jovin case?' (As if they would explain.) And then accept the banal,

`Nothing.' And then never bother to follow up, `well, what exactly are you

doing? Are you checking other crimes involving knives? Are you checking with

other municipalities? Are you checking the floors of impounded cars for trace

evidence? Are you soliciting information from arrested felons?' No one asks. As

I see it, the Connecticut media is no better than the Germans in the '30s and

'40s who sat by blindly and questioned nothing as a group of political criminals

took over the country and led it into murderous ruin."

Oct. 31: "There is a reason why the constitution protects privacy and insists on

equal protection - it's not to protect the victim, but to protect society from

capricious investigation. By definition, I AM INNOCENT! I have not even been

arrested, yet many have condemned me. This should alarm and concern you

tremendously. Yale University and the State ended my political career, my

broadcasting career, my academic career, many friendships and relationships and

drained my life savings - merely by purposefully whipping up hysteria and naming

me within days of the crime, before investigating the crime. It's a form of

character destruction which the Courant participated in. It is an utterly

frightening and disgusting aspect of our current society. All journalists and

editors first and foremost, like doctors, should pledge to do no harm. Yet in

this case, CT journalists were willing partners of the State and may have kept a

murderer free by participating in capricious State activity. The case is clearly

an absolute joke. It's a joke of an investigation, an insult to our careful

judicial system, an insult to the Edgehill and Yale communities and left the New

Haven community weaker.

"My goal, since no one in the Connecticut media seems interested, is to bring

some critical thinking to the investigation."

Van de Velde's cutting words hit home in a couple of ways. First, critical

thinking is the key to my profession, and the point I stress above all others

when I teach. Second, what became crystal clear, not just in those e-mails but

in five months of investigation, is despite all his outrage, Van de Velde is

desperate for help from the same media he blames so much for his situation.

James Van de Velde loathes us.

James Van de Velde needs us.

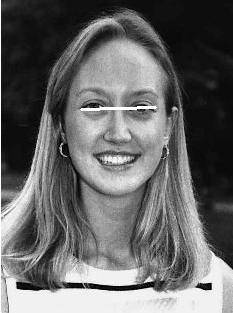

[picture]

Suzanne Jovin was a political science major at Yale University completing her

senior year when she was murdered Dec. 4, 1998. (Photo courtesy New Haven

police)

Inevitably, the two adjectives used in newspaper and magazine articles and in

television interviews to describe Suzanne Jovin are "brainy" and "beautiful."

The daughter of American scientists, Thomas and Donna Jovin, she lived in

Gottingen, Germany, where they worked, before entering Yale in September 1995.

Jovin was an excellent student with broad interests. As her senior year began,

the political science major was accepted into one of the two seminars being

taught that fall, 1998, by Van de Velde, "Strategy and Policy in the Conduct of

War." She also asked Van de Velde to be her senior essay advisor; she would be

one of six students he advised that term on essays. Unlike many upwardly mobile

Yale students who ask high-profile professors to be their senior essay advisors

- the better to use for future reference as they head out into the world - Jovin

stuck with a lecturer whose specialty was the field she wanted to pursue.

Friends, Yale officials and those who knew her can't always put into words what

made Jovin special. "Suzanne was just one of those people who are absolutely

incredible, just warm and brilliant," said Bailey Hand, a friend in the Strategy

and Policy seminar. "I remember thinking Wednesday of that week (two days before

Jovin was slain), I looked at her while she was saying something in class,

thinking how wonderful that someone like that is alive in this world, 'cause

she's going to make such a difference." Susan Hauser, the former director of

Yale's undergraduate career services office where Jovin worked, described her as

"extremely bright, interested, generous, considerate, warm, fun." In her senior

year, Jovin became president of Yale's campus chapter of Best Buddies, an

international program that pairs people with mental retardation with college

students for social get-togethers. Dawn DeFeo was the host site coordinator for

Marrakech Inc., the New Haven-based agency that matched the adults with the

students. She called Jovin, who had been with Best Buddies all four of her Yale

years, "inspirational in everything she did. She was very bubbly, and the type

of person everyone would admire because of the energy level she had and the

enthusiasm."

Jovin began the last night of her life, Friday, Dec. 4, with a pizza party for

Best Buddies at Trinity Lutheran Church on Orange Street in New Haven, a few

blocks from her university-owned apartment on Park Street. It was the end of the

semester, and Jovin told friends she was looking forward to a chance to return

to Germany. She also had been through some turmoil with her senior essay, on the

international terrorist Osama bin Laden, sweating out until Wednesday, Dec. 2,

until she could review her first draft with Van de Velde, who had been tardy in

reading it and giving her feedback. Still, on Friday afternoon, she swung by

Brewster Hall, the white-pillared political science building on Prospect Street,

and dropped off a second draft, asking Van de Velde in a breezy, handwritten

note to peer at some of the revisions she had made. Her final draft was due the

following Wednesday. Sean Glass, a sophomore in the Best Buddies program,

recalls Jovin being "very happy" at the party that night, talking about seeing

her family again. "I don't remember her seeming to be upset about anything."

The sequence of events once the party ended, about 8:30 p.m., has been pieced

together from various sources - some from the police, others from witnesses.

Jovin, after helping clean up, left the party in a university-owned car

available to students for such events, dropping off at least one person, then

parking the car at a lot at Edgewood and Howe streets, and walking a couple of

short blocks back to her apartment. There, she e-mailed a friend just after 9

p.m., promising to leave some books for her in her building's lobby.

|

|

Half an hour later, at 9:58 p.m.,

Jovin's

body was found face down, feet touching the street and body stretched across a

grassy part of sidewalk, nearly two miles away, at

Edgehill

and East Rock roads, an upscale residential section. A soda bottle was found in

bushes nearby; it bore only

Jovin's fingerprints. Police

reported that witnesses heard a man and woman arguing loudly about 9:45 p.m.

Jovin

had been stabbed 17 times in the back, neck and back of the head. The tip of the

weapon used was later recovered from her head. Although police in the early

stages confirmed certain information, such as the number of wounds and the fact

that they believe the crime was committed by someone who knew the victim, they

have never discussed many logical questions, even the simplest ones. What was

the substance of the argument reported? What about the question overheard by

some witnesses: "Why are you doing this to me?" Is it known whether anything

overheard that night was, in fact, connected to

Jovin's

death?

[picture]

Van de Velde was an altar boy at Holy Infant Church in Orange, Conn. Here is

pictured with the Rev. Howard Nash (Photo courtesy James Van de Velde).

Inevitably, the two adjectives used by

reporters to describe Van de

Velde are "cool" and "mysterious."

But that appears to be an outgrowth of his professional background. Ironically,

his training is rooted in honor and trust, traits Van de Velde's family and

friends say were evident from his earliest days; they say he didn't get into

fights or adolescent hijinks. He grew up in Orange and was a top student and

athlete at Amity Regional High School in Woodbridge before going on to

graduate from Yale in 1982. His higher training - he holds a doctorate in

international security studies from Tufts University's Fletcher School of Law

and Diplomacy and has a top secret government security clearance as a lieutenant

commander in the U.S. Naval Reserve - led him through a series of government and

education positions in the U.S. and abroad for the State Department during the

administration of President George Bush.

Van de

Velde

left government service to rejoin his alma mater as dean of

Saybrook

College, one of Yale's residential dormitories, in the fall of 1993. He

held the position, which included

supervising Saybrook's

475 students, for four years, and during that time taught some unusual

policy courses within the political science department, classes he designed

himself. Evaluations of Van de Velde by students were glowing; he studiously

prepared and handed out class notes for each session. His "International Drug

Trafficking: National Security Dimensions and Drug Control Strategies" class was

named by Spin magazine as one of the most interesting college courses in the

country. Van de Velde brought crisis management games to Yale, working with

friends from the Naval War College, where he did his work in the Navy Reserve.

In the spring of 1997, he took a leave from Yale on a Navy assignment to help

monitor the status of peace in Bosnia from a base in Italy. After returning to

finish out the term, he left Yale to become

deputy director of the Asia/Pacific

Research Center, part of Stanford University's Institute for International

Studies. But the position on the West Coast didn't work out. Henry Rowen,

Asia/Pacific's co-director, said after just a few months, several faculty

members had come to him to discuss problems with Van de Velde, who he indicated

was "a little stiff" in handling administrative matters. Rowen and Van de Velde

talked largely about the job's focus on administration rather than policy. The

result was an agreement that the job wasn't best for Van de Velde, who was far

more interested in policy, Rowen said. Van de Velde decided to come back home.

Professor David Cameron, then chairman of Yale's political science department,

hired him as a lecturer of two fall seminars: the Strategy and Policy course,

and "The Art of Diplomacy: Negotiating, Crisis Management and the Role of Force

in International Politics."

[picture]

Van de Velde as an officer in the U.S. Naval Reserve.

With his training and combined government and education backgrounds, Van de

Velde was beginning to figure out his life's goal. What he really wanted was to

be a television commentator on foreign affairs who also could find time to be a

college lecturer. Toward that end, he enrolled in Quinnipiac's master's program,

which he hoped would give him the basics in journalism. And he sought to obtain

an internship at one of the state's local television stations. Months later, the

story of how Van de Velde moved from one television station to another became an

eyebrow-raising issue among the media. Yet the story is quite simple, and

confirmed by the parties involved. Van de Velde had sent out queries to all of

the stations, and was initially accepted as an intern by WTNH Channel 8 in New

Haven. He started there in early September. That week, however, were the first

sessions of his seminar and the start of his news reporting class at Quinnipiac.

He had more than 80 students enroll in each of his two Yale seminars, and he had

to whittle that down to about 20 in a week. Faced with that task and his other

demands, he told WTNH he wouldn't be able to do the internship, and the two

sides parted company amicably. Meanwhile, Van de Velde began settling into his

routine at Yale and Quinnipiac. Two weeks later, he suddenly heard from a news

official at WVIT, Channel 30, in West Hartford who had been away on vacation.

Feeling more in command of his time, Van de Velde agreed to begin work at WVIT

two days a week.

As his professor at Quinnipiac, I was annoyed when Van de Velde twice failed to

hand in assignments. His classroom presence was quiet; he was not confident of

what he was learning and held back more than the other students. Several of his

Quinnipiac classmates said they thought Van de Velde was aloof and unfriendly.

One, Joyce Recchia, recounted a story in which she approached Van de Velde

during a class break to inquire about a Yale doctoral program in political

science. Recchia had obtained a master's degree in the field, same as Van de

Velde's. She said he told her she wouldn't like it, but that the message he

conveyed was she couldn't handle it. She said she felt his response was so cold

that she avoided him as much as possible the rest of the semester. Several

others recalled an incident I had forgotten, during which, as the students

pursued an in-class writing assignment, I went around asking various questions.

When I got to Van de Velde and asked him about the missing assignments, he

turned around and said curtly, "I don't have them," and turned back to his tube.

It didn't help his reputation among his peers.

What I remember about Van de Velde was his pursuit of his goals and the

swiftness with which he learned a new trade. His work started out mediocre,

common for fledgling reporters, but by semester's end was quite good. Van de

Velde also wrote me a lengthy e-mail - sign of things to come - in mid-semester

apologizing for his failure to complete some assignments and advising me to give

him an "F" on those papers. In the e-mail, he mentioned his dream of doing

foreign affairs, and spoke of WVIT possibly giving him a chance to do short

background detail pieces on foreign issues such as "Kosovo, the Middle East

peace talks, North Korea, ballistic missiles." He asked if, rather than working

with him on the varied assignments we would have for the rest of the semester, I

would help him by editing such pieces (I offered to look at the TV pieces as a

favor, but wouldn't let him off the hook on the class assignments). He said he

didn't plan to complete the Quinnipiac program, mentioning that this might be

the only course he would take.

He said in the e-mail:

"Of course, your course teaches the basics well and I should study the basics

hard to attempt to add the discipline of journalism to my credentials. But

frankly, my life precludes this realistically:

"I teach full time at Yale;

"I have 8 [sic] senior essays, a directed reading project, two articles pending,

a grant proposal, a web site, a web game, two new courses to design, and spend

two full days a week at WVIT! My students at Yale, you can understand, come

before anything else in my professional life, especially my personal interest in

learning the art of journalism; and preparation for course teaching is quite

time consuming.

"I am a Navy reservist and spend one weekend away every month!

"I endeavor to be a normal human too!"

For Van de Velde, the future would be anything but normal.

Van de

Velde

visited the White House in 1989 while he was executive secretary to an

ambassador in the U.S. delegation to nuclear space and arms talks with

the Soviet Union.

Hours before he raised a glass with his Quinnipiac classmates at

Dickerman's,

Van de Velde had been questioned briefly by police at his office. They

asked if he knew of anyone who might want to hurt Jovin, if he was aware of any

problems she had been having. All the routine stuff you would ask those in a

certain circle, he said. The session with the two detectives lasted 15 or 20

minutes.

The next day, Tuesday, Dec. 8, Van de

Velde

arrived home from the gymnasium in the late afternoon and saw a police car

outside his place, in the church house at Bethesda Lutheran Church on St.

Ronan Street. Detectives knocked on his door after he got inside and asked him

if he minded coming to the station for some more questions. So he drove his

candy-apple red Jeep down to the station. Thus

began a four-hour interrogation that Van de

Velde

says had all the elements of classic policing. He had learned about

interrogation during some of his military training. Although it was unpleasant

to be the brunt of such a probe - which alternates accusatory questions with

manufactured witnesses, lies and sympathy, all in an effort to entice the

subject to confess - Van de Velde said a part of him was fascinated to see such

techniques in action. He said, however, he calmly answered every question put to

him, and offered the police the keys to his vehicle, as well as to take a lie

detector test, give blood and have his apartment searched. The police took him

up only on searching the car.

The police have never given their version of what went on in the interview.

Van de

Velde

went home convinced, he said, that "that was that." He said he figured

they were doing this with quite a few people who were closest to Jovin. But the

next morning, The New Haven Register's lead headline was "Yale Teacher Grilled

in Killing." Though the story didn't name him, it didn't take long for many to

determine who the suspect was. Van de Velde saw the story while at his office;

dazed, he walked out Prospect Street for a 9:45 a.m. cleaning and checkup with

his dentist. The idea that police had leaked his being questioned to the media

made him realize his was not a routine experience shared by others. As if to

pound the point home, a television news reporter approached Van de Velde on the

street and, with cameras rolling, abruptly asked if he would ever harm Jovin.

The image of a startled Van de Velde, not quite knowing how to respond (he

answered "no"), or even whether to respond, helped cement a public perception of

guilt that still lingers for many who watched the noon news on Channel 8 that

day.

The New Haven Police Department has kept its theories about Jovin's death to

itself. Police Chief Melvin Wearing declined to discuss specifics for this

story, saying the case remains an open investigation.

Though there was little official news from the beginning, the police anonymously

leaked many tidbits in the days and weeks after the slaying. Members of the

media were quick to go after each morsel, beginning with the big one, that a

Yale lecturer was being questioned. (The initial Register story was attributed

to "city and university sources close to the case," but clearly, the police had

to have been talking to others for the information to get to the newspaper.)

What the police believe happened can be deduced by examining department

statements over the months, and by looking at the fact that Van de Velde

continues to be the only named suspect.

When investigating a homicide, police look for motive, means and opportunity.

Van de

Velde,

who lived less than half a mile from where

Jovin's

body was found, had no alibi. He has insisted he worked late the night in

question, then went home, where he remained, watching television and eating

leftovers.

With opportunity in hand, police looked to motive. Their initial theories of a

potential love interest between Jovin and Van de Velde didn't materialize; none

of the students interviewed even hinted at such a possibility, though police

would continue to try even months later to get students to confess to having had

affairs with Van de Velde. Soon after the murder, though, police learned from

family and some friends that Jovin

had been extremely upset with Van de

Velde

because he had taken so long to give her feedback on her senior essay.

David Bach, one of her closest friends on campus, and Jovin's parents have told

reporters she was in tears over the lack of feedback. The police also learned

that Van de Velde had applied for an assistant professorship that fall, a

tenure-track position. Perhaps most important, they interviewed some television

newswomen, including one Van de

Velde

had dated a year earlier. What these women said appears to be one of the

central issues in Van de Velde's becoming the focus of the police investigation.

Their comments apparently gave police the idea - again, an idea later leaked

anonymously to reporters - that Van de

Velde

could have a history of stalking women.

Now police felt they had a possible motive -

Van de

Velde

and Jovin

get into an argument and she threatens to report him for something - and

they believe there is opportunity, since Van de Velde couldn't prove his

whereabouts. So how does that translate to the murder in question? Jovin was

last seen walking north on College Street near Elm Street, which means police

must follow one of these theories:

Van de Velde meets Jovin on the street, perhaps following her from her

apartment, and he persuades her to come with him in his Jeep, which must have

been parked nearby.

Van de Velde, perhaps waiting in his Jeep outside her apartment, sees her leave

through the Old Campus and cruises the neighborhood, eventually persuading her

to come with him.

Van de Velde waits for Jovin, sees her return to her apartment and calls her

there to arrange for a brief meeting, perhaps with the enticement of returning

the second draft of her essay. A slight variation here would be that the two

made an appointment earlier, perhaps when she dropped off the second draft

earlier in the day, for later in the evening.

Regardless of the theory, police believe Van de Velde hooks up with Jovin -

one witness told Vanity Fair magazine she saw him walking behind

Jovin

on College Street, though she didn't report this to police until after

she saw Van de Velde's face on the Channel 8 interview. Van de Velde begins to

drive Jovin toward his side of town for reasons unknown - police may speculate

he wanted to soothe her anger, or perhaps they believe he was secretly smitten -

and something goes wrong. She leaves the vehicle, and Van de Velde follows, at

some point in a murderous rage, stabbing her 17 times on the street and driving

off.

Following this rage theory, it stands to reason police must believe the murder

was not premeditated. Clearly, if Van de Velde, a smart, disciplined person, had

planned it in advance, he would have had an alibi. Also, if he had planned this

in advance, why would he take the

enormous risk of being seen with

Jovin downtown on a warm Friday

night? Likewise, if they had made an advance appointment, he would have

been taking a risk that she might tell someone else. Thus, police must believe

the murder is an act of rage, and possibly passion, done spur of the moment.

Logically, since it was not planned in advance, police must believe Van de Velde

used his own vehicle and that he had a propensity for either carrying a knife or

having one in his vehicle. The weapon used to kill Jovin was never found.

Suzanne Nahuela Jovin (b. January 26, 1977, Göttingen, Germany - d. December

4, 1998, New Haven, Connecticut) was a senior at Yale University in New Haven,

CT when she was brutally stabbed to death off campus. The city of New Haven and

Yale University have offered a combined $150,000 for information that leads to

the arrest and conviction of Jovin’s killer [1]. The crime remains unsolved.

Jovin was born and raised in Göettingen, Germany, the third of four daughters,

to scientists Donna and Thomas Jovin. Fluent in German, English, French, and

Spanish, and a visitor of four continents, Jovin chose to expand on her passion

for international diplomacy and public service in college, majoring in political

science and international studies. It was this love of public service – of doing

good for others – that motivated Jovin to join the New Haven chapter of Best

Buddies. Jovin also volunteered as a tutor through the Yale Tutoring in

Elementary Schools program, sang in both the Freshman Chorus and the Bach

Society Orchestra, co-founded the German Club, and worked for three years in the

Davenport dining hall. [2]

Contents [hide]

1 The Murder

2 The Evidence

3 The Investigation

4 Litigation

5 Theories

6 External links

[edit] The Murder

After dropping off the penultimate draft of her senior essay on the terrorist

leader Osama bin Laden, at approximately 4:15pm on December 4, 1998, Suzanne

Jovin began preparations for a pizza-making party she had organized at the

Trinity Lutheran Church on 292 Orange St. for the local chapter of Best Buddies,

an international organization that brings together students and mentally

disabled adults. By 8:30pm, after staying late to help clean up, she was driving

another volunteer home in a borrowed university station wagon. At about 8:45 she

returned the car to the Yale owned lot on the corner of Edgewood Ave and Howe St

and proceeded to walk two blocks to her second floor apartment at 258 Park

Street, upstairs from a Yale police substation.

Sometime prior to 8:50, a few friends passed by Jovin's window and asked her if

she wanted to join them at the movies. Jovin said no-- that she was planning to

do school work that night. At 9:02, she logged onto her Yale e-mail account and

told a friend to she was going to leave some books for her in her (Jovin’s)

lobby. At 9:10 she logged off. It is uncertain if she made or received any

calls; calls within Yale's telephone system were not traceable. She wore the

same soft, low-cut hiking boots, jeans, and maroon fleece pullover she had worn

at the pizza party. [3]

Very shortly thereafter, Jovin headed out on foot to the Yale police

communications center under the arch at Phelps Gate on Yale’s Old Campus to

return the keys to the car she had borrowed. Shortly before reaching her

destination, at about 9:22, Jovin encountered classmate Peter Stein who was out

for a walk. Stein is quoted by the Yale Daily News as saying "She did not

mention plans to go anywhere or do anything else afterward. She just said that

she was very, very tired and that she was looking forward to getting a lot of

sleep." [4] Stein also said Jovin was not wearing a backpack, was holding one or

more sheets of white 8 ½ x 11 inch paper in her right hand, that she was walking

at a "normal" pace and did not look nervous or excited, and that their encounter

lasted only two to three minutes [5].

Based on the timeline, it is presumed

Jovin

returned the keys to the borrowed car at about 9:25. She was reportedly last

seen alive at between 9:25-9:30pm walking northeast on College Street, but not

yet past Elm Street, by another Yale student who was returning from a Yale

hockey game. The two never spoke. [6]

At 9:55, a passerby dialed 911 to report

a woman bleeding at the corner of

Edgehill

Rd and East Rock Rd, a posh neighborhood 1.9 miles from the Yale campus where

Jovin

was last seen alive. When police arrived at 9:58, they found

Jovin

fatally stabbed 17 times in the back of her head and neck and her throat slit.

She was lying on her stomach, feet in the road, body on the grassy area between

the road and the sidewalk. She was fully clothed and still wearing her watch and

earrings, with a crumpled up dollar bill in her pocket; her wallet later found

to be still in her room. Suzanne

Jovin was officially pronounced

dead at 10:26 at Yale New Haven Hospital [7].

[edit] The Evidence

Many items and observations have been reported by the police and media as

possible evidence over the nine plus years of the investigation, much of which

has either been discredited, deemed hearsay, unreliable, or been explained. The

most reliable physical evidence appears to be: 1) DNA found in scrapings taken

from under the fingernails of Jovin’s left hand [8], 2) Jovin’s fingerprints and

an unknown person’s partial palmprint found on a Fresca bottle in the bushes in

front of where her body was found [9], and 3) the tip of an estimated

4-5 inch non-serrated carbon steel blade lodged in her skull [10]. The

most reliable observation appears to be the sighting by more than one individual

of a tan or brown van at the precise location where Jovin’s body was found.

The existence of the tan/brown van was not made public by the New Haven Police (NHPD)

until March 27, 2001, when they wrote: “witnesses have said that as they

approached the corner of East Rock and Edgehill Roads, they saw a tan or brown

van stopped in the roadway facing east, immediately adjacent to where Suzanne

was found.” [11] Although members of the Yale faculty had reported the police

were asking privately about the van at the inception of the investigation, no

explanation has ever been given why it took more than two years to release the

information to the public. Although the New Haven Register reported on November

8, 2001, that the NHPD had impounded a brown van as part of the Jovin

investigation, no link has ever been confirmed [12]. There have been no reports

of anyone witnessing Jovin enter or exit any vehicle nor has the observed van

apparently been found.

The existence of the Fresca bottle came to light on April 1, 2001, by Hartford

Courant reporter Les Gura [13] The only store in the vicinity of campus that

sold Fresca open at the hour Jovin was last seen alive was Krauszers market on

York St near Elm St – precisely one block south of Jovin’s apartment. Although

Krauszers maintained a video recording of its customers for security purposes,

the police never asked to view their tape and have never reported seeking

assistance from store employees or customers about whether they had seen

anything unusual that night. The foreign palmprint has yet to be identified.

The first mention of the existence of the DNA was on October 26, 2001, following

a solicitation by the New Haven police for colleagues, friends and acquaintances

of Jovin to come forward and give DNA samples voluntarily [14]. No explanation

has ever been given why it took nearly three years for the fingernail scrapings

to be tested for DNA. No match has yet been found.

[edit] The Investigation

A mere four days after the murder, the name of Jovin’s thesis advisor, James Van

de Velde, was leaked to the New Haven Register as the prime suspect in the case.

Fifteen months later, criminologist John Pleckaitis, then a sergeant at the New

Haven Police Department, admitted to Hartford Courant reporter Les Gura: "From a

physical evidence point of view, we had nothing to tie him to the case ... I had

nothing to link him to the crime." [15] Famed criminologist Henry Lee’s offer to

reconstruct the crime scene was accepted by the police but for reasons unknown

never acted upon [16].

Based on subsequent questioning of the Yale community, and based on Van de

Velde’s name being released prior to the completion of his police interrogation,

it became apparent the NHPD

had for reasons unknown convinced itself that Van de

Velde

and Jovin

must have been having an illicit or unrequited affair-- a notion that

friends of Jovin, not to mention her boyfriend, found offensive, false and

wholly unlikely [17]. Nevertheless, with no physical evidence nor a motive, the

NHPD continued to maintain that their naming of Van de Velde was not

presumptuous. An apparently unquestioning Yale, under the guidance of

Dean Richard Brodhead, then chose to

cancel Van de Velde’s

spring 1999 classes citing his presence as a “major distraction” for students,

thus destroying his reputation and academic career [18]. Brodhead would later

become the President of Duke University where he became best known for his rush

to judgment in disbanding their lacrosse team based on equally dubious

accusations that were later proven to be false and malicious. [19]

In 2000, Van de Velde and colleagues strongly and eventually publicly encouraged

Yale to hire their own private investigators to study the case. In December,

2000, under additional pressure from the Jovin family,

Yale relented and hired the team of

Andrew Rosenzweig,

former chief investigator with the New York district attorney's office, and Bill

Harnett, a former homicide detective from the Bronx, NY [20]. It was at their

insistence that the NHPD finally allowed the state forensics lab to analyze

Jovin’s fingernail scrapings for DNA. Neither the resulting DNA nor Fresca

bottle fingerprint was a match to Van de Velde, prompting Harnett to label Van

de Velde “Richard Jewell with a Ph.D” [21] [Jewell was a hero security guard

falsely accused by the FBI of the Centennial Park bombing during the 1996

Olympics in Atlanta, GA]. No explanation has ever been given why Yale has chosen

to keep the results of their investigation a secret.

The

NHPD

responded by contacting the US Navy, Van de

Velde’s

primary employer at the time, urging them to reconsider their contract work with

him-- going so far as to travel to Washington DC to offer their “assistance.”

A thorough review was conducted that resulted in Van de Velde being allowed to

keep his job and his security clearance [22]. Sensing the investigation had

dead-ended on him, Van de Velde undertook a letter writing campaign urging the

Connecticut State cold case unit to take over the case [23]. When the Chief

State’s Attorney refused, Van de Velde began pressing the police to undertake

additional state-of-the-art forensic tests on the evidence [24].

On September 1, 2006, nearly eight years after the murder, the Jovin

investigation was officially classified a cold case and moved to the

Connecticut’s Cold Case Unit [25]. However, the case was never added to the Cold

Case Unit web site nor was there any mention of the reward being

offered—prompting Van de Velde once again to write letters of complaint. On

November 29, 2007, Assistant State’s Attorney James Clark admitted that the case

had been secretly reassigned back to New Haven in June of that year, this time

under the auspices of a handpicked team of four retired detectives. According to

Clark: “no person is a suspect in the crime, and everyone is a suspect in the

crime.” [26]

[edit] Litigation

On January 12, 2001, Van de

Velde

sued Quinnipiac University for wrongfully dismissing him from a graduate program

he was enrolled in there [27]. Van de

Velde

agreed to drop the lawsuit on January 26, 2004, in exchange for $80,000. [28]

In December 7, 2001, Van de Velde sued the NHPD claiming they violated his civil

rights by naming only him publicly as a suspect while claiming that other

suspects existed as well [29]. Van de Velde added Yale as a defendant on April

15, 2003. [30] Both suits were dismissed on March 29, 2004 [31]. Van de Velde

appealed, but in April 2006 Connecticut District Court Chief Judge Robert

Chatigny ruled against him. Van de Velde asked Chatigny to reconsider in May of

2006, resulting in the judge reinstating just the state claims on December 11,

2007. [32]

[edit] Theories

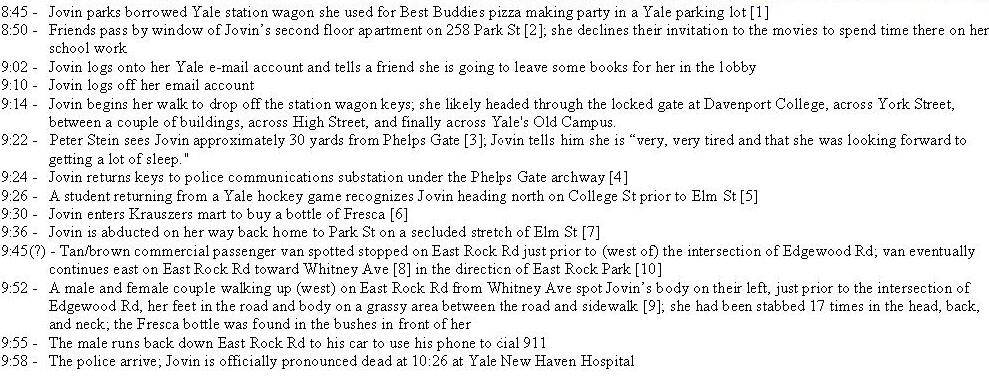

Google satellite maps of Jovin’s most probable route on the night of her murder

may be viewed at: http://siliconinvestor.advfn.com/readmsg.aspx?msgid=24166152

Jovin’s

route across Yale’s gated Old Campus, which is off-limits to cars, makes it

quite unlikely she was trailed by someone in a vehicle. The timeline,

distance to where she was found dead (1.9 miles), her clothing, what she said to

friends, etc. strongly indicate a vehicle was used to transport her off campus,

making it also quite unlikely Jovin was followed on foot. Combined, this

significantly lowers the chances Jovin was stalked.

The witness who saw her on the Old Campus said she wasn’t holding a Fresca,

which means she most likely bought one (note: Jovin was known to like Fresca,

making it less likely someone had offered her one randomly) at Krauszers market

on the corner of York St and Elm St. on her way back home. The only place for a

car to be introduced here would be in front of the store or, more likely, on the

secluded stretch of Elm between York and Park next to, or in front of, the

boarded up Daily Café.

To establish a “she knew her killer” scenario would require, after just telling

people how very tired she was and looking forward to being home to rest, in the

one-block area between Krauszers and her apartment: a) she ran into someone she

knew well enough to get into their car, b) she had a compelling reason to get

into their car, c) whatever conversation that took place got heated enough in a

matter of minutes to lead to a vicious murder, *and* d) this unscheduled

encounter involved someone who just happened to have a knife on them. Possible,

yes, but not probable.

The Fresca bottle containing both Jovin’s fingerprints and an unknown person’s

palmprint was found in the bushes in front of where her body was found. People

who flee from a car driven by an attacker likely do not take their soda bottles

with them. People who are run down outside and stabbed 17 times would likely

scream loudly and consistently for help, put up a fight, and leave a trail of a

massive amount of blood. There is no evidence any of the above happened, let

alone all of it. The most likely scenario is Jovin was attacked in the tan/brown

van observed by several witnesses and then dumped, along with the Fresca bottle,

which would account for her proximity to the road. That Jovin a) did not drop

her Fresca prior to entering the vehicle, b) was not able to flee the vehicle,

and c) had no defensive wounds, likely implies overwhelming force, suggesting

perhaps more than one person was involved in her abduction.

While multiple stab wounds often indicates a crime of passion, it can indicate

rage or drug use as well. As foreign DNA does not ordinarily transfer to

underneath one’s fingernails with merely “routine” contact, it is reasonable to

conclude that Jovin scratching her attacker might have precipitated his rage.

However, given a) the reported 4-5 inch

size of the knife used to stab

Jovin, b) that the tip of the

knife broke off in her skull, c) that the killer saw fit to slit her throat,

likely after stabbing her 17 times, and d) that she was found barely

alive, one has to consider the possibility that perhaps the flimsy nature of the

murder weapon necessitated inflicting the high number of wounds.

As Jovin was fully clothed with no reported tears in her outfit and

no defensive wounds, while an attempted sexual assault can not be ruled

out, there is no basis to assume this was the motive. As Jovin was found in a

residential area that was void of ATMs, was still wearing her jewelry, and still

had a dollar bill in her pocket, it is hard to assume that her abduction was a

robbery gone bad… unless the killer became enraged that she had left her wallet

in her apartment or unless the killers were looking for quick cash en route down

East Rock Rd to East Rock Park to buy drugs, a known druggie hangout. Some have

speculated Jovin’s thesis on

Osama

bin Laden may have made her a terrorist target, but given she used no

live sources, given this was nearly three years prior to 9-11, and given Al-Qaeda

has no history of such attacks, this notion seems quite improbable.

[edit] External links

Nine years later, murder of Yale senior still unsolved

As Jovin Investigation Team debuts, interviews suggest holes in original police

inquiry

Print Email Write the Editor Share Digg Facebook Newsvine Reddit Rachel Boyd

Staff Reporter

Published Wednesday, December 12, 2007

Your Name

Your Email

Friend's Name

Friend's Email

Message

Submit Close

Less than six hours before she was killed, Suzanne Jovin, a 21-year-old Yale

student, turned in a draft of her senior essay.

It was Dec. 4, 1998, just a week

before the final copy was due. In 21 single-spaced pages on “Osama bin Laden and

the Terrorist Threat to U.S. Security,” she examined the terrorist’s already

prominent organization. Her paper was virtually complete, except for the

conclusion. In neat handwriting on the margins of page 20, she wrote about the

final paragraphs: “I’m saving the conclusion for last.”

“She had a few hours more work to go,” says

James Van de

Velde

’82, her senior essay adviser and the instructor of her political science

seminar, “Strategy and Policy in the Conduct of War.”

In the unfinished paragraphs, which were provided to the News by Van de Velde,

she ended her paper with a warning to foreign-policy makers: “To ultimately

defeat bin Laden in his ‘holy war’ against the United States and the

non-Muslims, we must be prepared to ‘stand some more heat.’ Certainly, there is

nothing to suggest that this ‘holy war’ will turn cold anytime soon.”

But Jovin would never know how true her words were. On that December night,

almost three years before Sept. 11, she was stabbed to death just two miles from

the Yale campus. And while al Qaeda’s holy war has certainly not turned cold

since 1998, it seems to Van de

Velde

that Jovin’s

unsolved murder investigation did — at least until two weeks ago.

Since September 2006, when Jovin’s case was handed over to Connecticut’s Cold

Case Unit, details about the investigation were almost impossible to come by.

The Unit refused to release any information about the status of their work, and

its Web site, which features photographs and details of nine other unsolved

murder cases dating back to 1982, had no mention of Jovin.

As the ninth anniversary of Jovin’s death approached, Van de Velde began to say

repeatedly that he wanted that to change — whether out of self-interest or not

is anybody’s guess — calling publicly on the Cold Case Unit to renew its

efforts. Van de Velde’s interest, after all, extends beyond that of a teacher

concerned about his student.

The former

Saybrook

College dean is also the only person ever named as a suspect in the murder.

His wish came true, or so it seems. At a Nov. 30 press conference outside the

New Haven Superior Court, State’s Attorney’s Office officials unveiled a new

Jovin Investigation Team charged with solving the Yale senior’s murder by

bringing fresh eyes to a crime that may have needed a more thorough effort from

the start, interviews with Jovin’s friends, police officers and local reporters

at the time have revealed. And just yesterday, after more than a year of

judicial silence, a federal judge resurrected Van de Velde’s claims against Yale

and the New Haven Police Department.

But whether the new team is anything more than a strategic response to Van de

Velde’s recent criticism — and whether the investigators will bring real closure

to the nine-year-old mystery — remains uncertain.

The stabbing

For early December, the Friday of the murder was unusually warm.

Jovin, an international studies and political science double major who grew up

as the daughter of scientists in Goettingen, Germany, spent the early evening at

New Haven’s Trinity Lutheran Church at a holiday pizza party with Best Buddies,

an organization that matches students with mentally disabled adults. She had

been involved with Best Buddies since her freshman year and was director of

Yale’s chapter.

Dawn DeFeo, who was then the coordinator of the supervised living arrangements

program at Marrakech, Inc., a not-for-profit provider of residential,

educational and career services for mentally challenged adults, says she met

with Jovin weekly to help organize Best Buddies activities. DeFeo was unable to

attend the Dec. 4 party, she says, because she was working part-time in order to

spend time with her young children. DeFeo says she tried, without much success,

to recruit other people from Marrakech to help Jovin coordinate Best Buddies

activities.

“It was really hard for Suzanne because I would put other people in charge, and

they weren’t really that responsive,” she says. Because no one from Marrakech

had volunteered to bring the buddies home after the party, Jovin had borrowed a

University station wagon so she could drive some of them back herself, DeFeo

recalls.

Around 9:25 p.m., a classmate, Peter

Stein ’99, saw Jovin

on Old Campus, he told newspapers soon after the crime. He said

Jovin

told him that she was returning the keys to the car and was planning to return

to her apartment on Park Street.

“She did not mention plans to go anywhere or do anything else afterward,” Stein

told the News in April 1999. “She just said that she was very, very tired and

that she was looking forward to getting a lot of sleep.”

Stein declined to comment for this article, saying he could no longer remember

details from the night of the crime.

Less than 20 minutes after Stein saw her,

Jovin

had been attacked.

At 9:58 p.m., police found her bleeding on the corner of Edgehill Avenue and

East Rock Road, about 2 miles from Old Campus, according to a 1998 NHPD press

release. The murder had occurred at about 9:45, according to the Department’s

description of the crime posted online in 2001.

Jovin

had been stabbed multiple times in the head, neck and back.

Some witnesses report having heard a scream and an argument between a man and

woman; others say they saw a tan or brown van in the street next to where

Jovin’s body was later discovered, according to the description.

Jovin’s

friend DeFeo

says she still does not think it was plausible that

Jovin

walked from Old Campus to the crime scene in just 20 minutes. She said she

doubts it was a random attack.

“I find it hard to believe that she

would have just gotten into a vehicle with somebody who she didn’t know; it

seemed it would have been more somebody who she knew,”

DeFeo

says. “But you hear so much, and it’s been such a long time.”

The ‘pool’ of suspects

Davenport Dining Hall Manager Jim Moule had planned an intense Saturday of

preparing for the college’s annual holiday dinner. The dining hall and common

room would be decked out with lights, white linens, ice sculptures, train sets

and dozens of pies and roasts by the night of Dec. 5.

But the usual cheer at the dinner was lost. Jovin, after all, had been a

favorite student worker for two years. “We were in a state of shock all day,”

recalls head pantry worker Pat McGloin. “We were all just walking around like

zombies.”

“It was very difficult to grieve when you had TV cameras aimed at the front and

back gates of the college,” Davenport College Master’s Senior Administrative

Assistant Barbara Munck says. “It was to me an imposition of our home.”

If the Yale community was looking for answers, so were the police. And officials

thought they might have found one in Jovin’s adviser, Van de Velde.

On the afternoon of Monday, Dec. 7, New Haven police officers interviewed him

briefly in his Yale office, for “10, 15 minutes tops,” according to Van de

Velde.

On Dec. 8, he says, police interrogated him for several hours at

NHPD

headquarters, asking him, among other things, whether he had killed

Jovin.

Then it all went public.

The next morning, The New Haven Register reported that a Yale “educator” was the

lead suspect in the investigation, citing “city and university sources close to

the case.” The bold banner headline, “Yale teacher grilled in killing,” was

one-and-a-half inches high. The Register claimed in the sub-heading that the

“prime suspect lives near where slain student was found, sources say.”

The article did not name Van de Velde outright, but at that point, he had

effectively been identified to the public, Van de Velde says. He lived only .6

miles from the scene of the crime, at 305 Ronan St., and since he was working as

a lecturer in the political science department, he was not a professor — a title

the Register article had been careful to avoid.

On Jan. 10, 1999, then-Dean of Yale

College Richard Brodhead called Van de

Velde

into his office, telling him that his spring term courses would be canceled and

that he could not advise any senior essays or directed readings, Van de

Velde

says. On Jan. 11, Yale Public Affairs Director Tom Conroy issued a statement

announcing that Van de Velde

was in a “pool of suspects,” although the University presumed him to be

innocent.

“Yale relieved Van de Velde of his spring term teaching after the New Haven

police identified him as in the pool of suspects for the Jovin murder,” Brodhead

wrote in an e-mail to the News last month. “The decision involved no presumption

of his guilt by myself or the [U]niversity. It followed from the recognition

that it would be inappropriate for his classes to take place under these

circumstances. He was not ‘fired,’ but

put on paid leave for the remainder of his appointment.”

Despite this declared presumption of innocence, students say the University’s

actions contributed to their suspicion of the faculty member.

“When Yale canceled his classes, I think most people on campus assumed that we

were all just waiting for the other shoe to drop, that the next thing you were

going to read about in the paper was that Van de Velde was arrested and charged

with the murder,” a former News reporter, Blair Golson, says. “I think we

assumed that Yale wouldn’t have done

what it had done unless it was acting maybe on more information than was

publicly available.”

Golson says that since he does not know what University administrators knew at

the time, he does not know whether the University made the right call.

Van de

Velde

was never charged, and no evidence has ever been presented to the public

to link him to the crime. Yet when he asked former Political Science Department

chair Ian Shapiro to re-hire him

after his one-year term expired, Van de Velde says, Shapiro refused. Shapiro did

not respond to phone and e-mail requests for comment on why Van de Velde was not

re-hired. His secretary said he was out of the country.

_____ until proven guilty

In his academic and professional life, Van de Velde often found himself coming

back to Connecticut.

He grew up in Orange, a middle-class suburb just miles from Yale. After studying

political science at Yale and graduating with honors in 1982, he earned a Ph.D.

from Tufts University in 1988. He went on to serve as a diplomat with the

Department of State, later joining the

U.S. Naval Intelligence Reserves and serving in several positions, from

Sarajevo to Singapore.

But Van de

Velde

says his true love was teaching. After serving as a lecturer in the Political

Science Department and Saybrook

College dean, Van de Velde

spent a year working in an administrative position at Stanford University’s

Asia-Pacific Research Center. In 1998, he returned to Yale because, he says, he

missed teaching college students, “didn’t particularly like being an

administrator of a research program,” and did not get along with a Stanford

faculty member.

After his one-year appointment at the University, he says he applied for a

“tenure-track” position within the department. His competition, he says, was

“All But Dissertation” graduate students and those with newly minted Ph.Ds. “I

feel that it was an outrage that I was not given the open tenure-track

position,” he says. “I am sure the Jovin matter had a lot to do with my not

landing [it].”

After the Jovin case, no university — or virtually any other organization —

would touch him, he says.

“For about a year, I couldn’t get a job

anywhere,” Van de Velde

asserts. “I applied to over 100 positions and couldn’t get an interview.”

Eventually, his prospects began to improve. The Navy gave him a series of 30-

and 90-day assignments in Washington, at one point assisting the Pentagon as a

“Y2K watch officer.” In 2003, the Department of Defense sent him to Cuba twice,

where he says he “interviewed detainees” at

Guantanamo

Bay. He says he then held a “top secret/codeword security clearance” with the

Department of Defense.

Van de

Velde

now resides with his wife and their 3-year-old son in a small town outside of

Washington, D.C., where he works on government contracts for

Booz

Allen Hamilton, a private consulting firm. He says he feels

“extraordinarily lucky for many reasons.” But he cannot leave the Jovin case

behind, because, he says, it will not leave him.

“It damaged my professional life; it damaged my personal life,” he says. “I lost

more or less all my professional acquaintances.”

Demonstrating how damaging the initial headlines were to Van de Velde’s

reputation, one Yale staff member who

claims to have known Jovin

says that even though Van de

Velde’s DNA does not match that

found under Jovin’s

nails, he could still have been involved in the crime. “I don’t know if he did

it or not, but I’m sure he was capable,” the staff member says, offering

no proof and insisting on remaining anonymous. In an e-mail to the News, Van de

Velde said the staff member’s statement is “trash.”

“Very few people in history have ever had their lives so totally inspected and

prodded through more than Van de Velde,” says Donald Connery, an author and

independent journalist who over the past 60 years has worked with NBC, Time and

Life magazines and United Press International. “And the authorities in this

state — the New Haven State’s Attorney General, the police, the Chief State’s

Attorney’s office — no one has the guts or the morality to simply say that this

man was falsely identified and is in no way a suspect.” In the 1970s, Connery

reported on Connecticut teenager Peter Reilly, who was wrongly accused and

convicted of his mother’s murder.

In 2001, Van de

Velde

began to come back onto the media’s radar. He filed defamation lawsuits

against Quinnipiac University — where he had been dismissed from a degree

program in broadcast journalism — and the Hartford Courant. The Courant lawsuit

is pending, and the Quinnipiac lawsuit was settled out of court in 2004 for a

“pretty generous” $80,000, according to Van de Velde. Lynn Bushnell,

Quinnipiac’s vice president for public affairs, and John Morgan, Quinnipiac’s

associate vice president for public relations, were both named in the lawsuit.

Both declined to confirm the amount of the settlement or to comment on the

lawsuit.

But the more attention-grabbing defamation lawsuit is the one in which Van de

Velde’s state claims were reopened yesterday. Van de Velde filed the lawsuit

against the NHPD in 2001 and added Yale officials to the lawsuit in 2003. He

claimed that the University and the

police leaked not only the fact that a “male Yale teacher” was the lead suspect,

but also that Van de Velde

himself was the suspect.

University President Richard Levin told the News last month that neither he nor

any other Yale officials acted as a source for the Register article. And when

asked whether Van de Velde is — or ever was — a suspect, New Haven Chief State’s

Attorney Michael Dearington said: “I wouldn’t get within 5,000 miles of that

question. I have never commented on that, and hopefully no one in my office has

ever commented on that.”

Cold case or no case?

In August 2007, 11 months after Jovin’s case was turned over to Connecticut’s

Cold Case Unit, Van de Velde sent a letter to Chief State’s Attorney Kevin Kane,

who oversees the unit. He urged Kane to post Jovin’s case on the Cold Case Web

site and asked him to examine 12 “avenues to investigate in the Suzanne Jovin

cold case homicide.”

“As both a citizen wrongly accused by the police and an analyst in the national

intelligence community, I have spent a lot of time thinking about the case and

how it might be solved,” Van de Velde wrote in the letter. “As you may know from

numerous press accounts, I have been, since the beginning of the case, the most

vocal advocate for a vigorous and truly professional police effort to solve the

crime.”

Among Van de Velde’s suggestions were examining the DNA of a set of fingerprints

on a Fresca soda bottle found at the crime scene; looking into other murders

committed by men driving vans, as may have been the case in Jovin’s murder;

examining a knife tip found in Jovin’s head to determine a manufacturer and type

of knife; comparing DNA found under her fingernails to DNA in the Connecticut

and Combined DNA Index System; conducting a sweat print analysis on her

clothing; performing a microscopic forensic analysis to determine the presence

of dirt, tire and other molecules on Jovin’s clothing; and looking into the Best

Buddies program.

Connery, the criminal law writer, sent a similar letter to Kane in February.

In an interview in mid-November, Kane said he received both letters but that he

chose not to respond. He declined to say why, and also declined to comment on

whether he had taken any of their suggestions. Kane says he does not believe all

cold cases are listed on the Cold Case Unit Web site. He declined to say why

Jovin’s is not.

Dearington, who was overseeing the investigation in New Haven, said in

mid-November that he had been forwarded Van de Velde’s and Connery’s letters,

but that he had no further comment. “I do know that the case is being actively

investigated by extremely experienced and qualified investigators,” he said. He

declined to say how many people are working on the Jovin case, although he

suggested that he would be more forthcoming in the future. “If you caught me on

a sunny day, maybe I’d say more,” he said Nov. 15. “I think, though, that as the

ninth anniversary [of Jovin’s murder on Dec. 4] approaches, we may provide more

information about what’s going on.”

A ‘brand new’ approach

In late November, Dearington’s words rang true. At the Nov. 30 press conference,

Assistant State’s Attorney James Clark announced the formation of a four-person

team of retired Connecticut detectives to look into the crime independently.

Each will earn just $1 a year for his work. The team will re-evaluate all

previously gathered information and will also seek out new leads, he said.

“The idea is to approach the case as if it were brand new,” Clark said.

“Therefore, no person is a suspect in the crime, and everyone is a suspect in

the crime.”

Also present at the press conference was Ellen Jovin, the sister of Suzanne

Jovin. Her family has long remained silent about the case – her parents declined

to comment for this article and her other sister, Rebecca Jovin, did not return

calls for comment. At the November press conference, Ellen Jovin spoke briefly,

asking people to contact the new squad if they have any information.

“Not knowing what happened to Suzanne is devastating for our family,” she said.

“Please do not let one more day pass in silence.”

In an interview five days after the team was announced, John Mannion, a retired

state police officer who is heading up the investigative team, said he had

already received information through new telephone and e-mail tip lines, but he

declined to give any more detail. Since June, he said, the team has been

reviewing the “expansive” case file on the murder.

Although state officials interviewed say the team has been meeting since the

summer, they gave different reasons for why the squad was not announced until

the end of November. Earlier in the month, both the Register and News published

front-page articles about Van de Velde’s unanswered letters; Van de Velde also

published a letter to the editor in the News in which he called on Yale

officials to clear his name and to push the Cold Case Unit to conduct tests on

evidence from the crime.

State’s Attorneys Clark and Dearington said the timing of the announcement had

nothing to do with Van de Velde’s recent appearances in the media and letters to

the State’s Attorney’s Office. But Mannion says media pressure had in fact

played a role in the announcement. “We thought it would be the appropriate time