US History Encyclopedia: Battle of Little

Bighorn

US History Encyclopedia: Battle of Little

Bighorn

Little Bighorn, Battle of (25 June 1876). The Sioux Indians in Dakota Territory

bitterly resented the opening of the Black Hills to settlers, which occurred in

violation of the Treaty of Fort Laramie of 1868. Owing also to official graft

and negligence, they faced starvation in the fall of 1875. They began to leave

their reservations contrary to orders, to engage in their annual buffalo hunt.

They were joined by tribespeople from other reservations until the movement took

on the proportions of a serious revolt. The situation was one that called for

the utmost tact and discretion, for the Sioux were ably led, and the treatment

they had received had stirred the bitterest resentment among them. But an order

originating with the Bureau of Indian Affairs was sent to all reservation

officials early in December, directing them to notify the Indians to return by

31 January under penalty of being attacked by the U.S. Army. This belated order

could not have been carried out in the dead of winter even if the Indians had

been inclined to obey it.

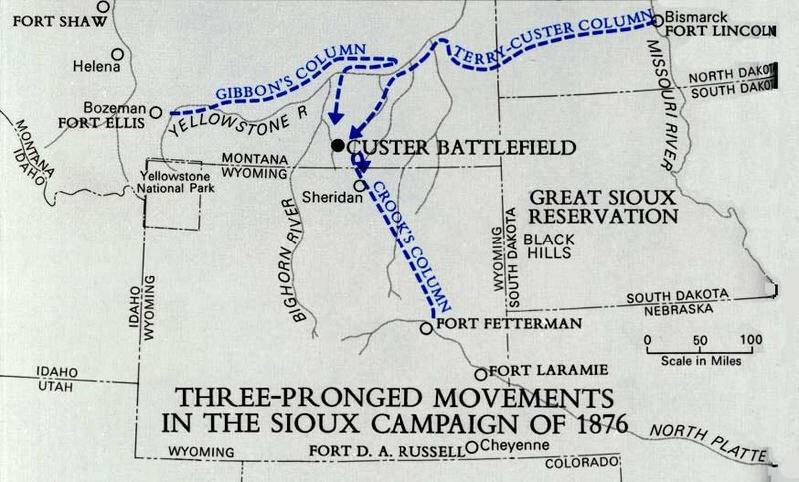

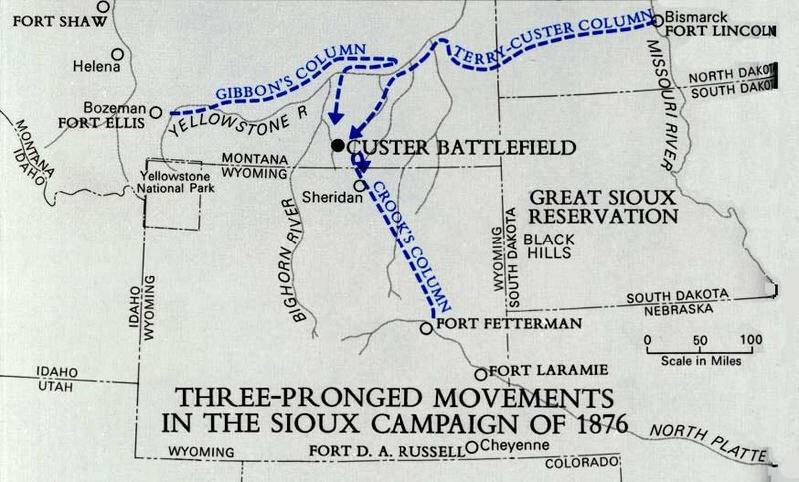

Early in 1876 Gen. Philip H. Sheridan,

from his headquarters at Chicago, ordered a concentration of troops on the upper

Yellowstone River to capture or disperse the numerous bands of Dakotas who

hunted there. In June, Gen. Alfred H. Terry, department commander, and Col.

George A. Custer, with his regiment from Fort Abraham Lincoln, marched overland

to the Yellowstone, where they were met by the steamboat Far West with

ammunition and supplies. At the mouth of Rosebud Creek, a tributary of

the Yellowstone, Custer received his final orders from Terry—to locate and

disperse the Indians. Terry gave Custer absolutely free hand in dealing with the

situation, relying on his well-known experience in such warfare.

With twelve companies of the Seventh Cavalry, Custer set out on his march and

soon discovered the Sioux camped on the south bank of the Little Bighorn River.

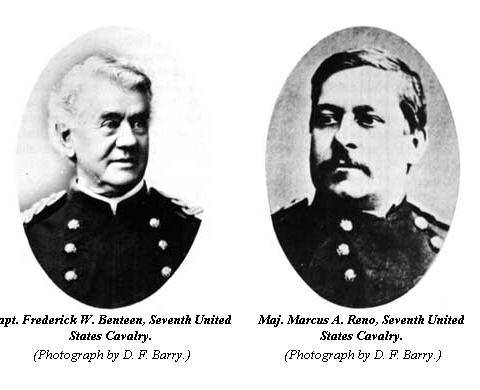

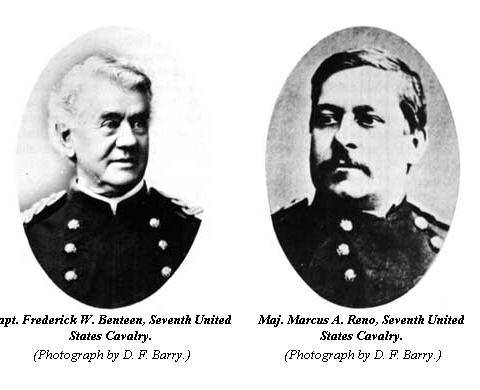

He sent Maj. Marcus Reno with three companies of cavalry and all the Arikara

scouts across the upper ford of the river to attack the southern end of the

Sioux camp. Capt. Frederick Benteen, with three companies, was sent to the left

of Reno's line of march. Custer himself led five companies of the Seventh

Cavalry down the river to the lower ford for an attack on the upper part of the

camp. One company was detailed to bring up the pack train.

This plan of battle, typical of Custer, was in the beginning completely

successful. Suddenly faced by a vigorous double offensive, the Indians at first

thought only of retreat. At this critical juncture, and for reasons still not

fully explained, Reno became utterly confused and ordered his men to fall back

across the river. Thereupon the whole force of the Indian attack was

concentrated upon Custer's command, compelling him to retreat from the river to

a position at which his force was later annihilated. The soldiers under Reno

rallied at the top of a high hill overlooking the river where they were joined

by Benteen's troops and, two hours later, by the company guarding the pack

train.

In 1879 an official inquiry into Reno's conduct in the battle cleared him of all

responsibility for the disaster. Since that time the judgment of military

experts has tended to reverse this conclusion and to hold both Reno and Benteen

gravely at fault. In Sheridan's Memoirs it is stated: "Reno's head failed him

utterly at the critical moment." He abandoned in a panic the perfectly

defensible and highly important position on the Little Bighorn River. Reno's

unpopularity after the battle was one of the reasons he was brought up on

charges of drunkenness and "peeping tomism" and court-martialed. Reno was found

guilty and dishonorably discharged. However, in December 1966 Reno's

grandnephew, Charles Reno, asked the Army Board for the Correction of Military

Records to review the court-martial verdict, citing disclosures in G. Walton's

book Faint the Trumpet Sounds. In June 1967 the secretary of the army restored

Reno to the rank of major and the dishonorable discharge was changed to an

honorable one. The action was taken on the grounds that the discharge had been

"excessive and therefore unjust." However, the guilty verdict still stands. In

September 1967 Reno was reburied in Custer Battlefield National Cemetery in

Montana.

As to Benteen, he admitted at the military inquiry following the battle that he

had been twice ordered by Custer to break out the ammunition and come on with

his men. Later, at 2:30 P.M., when he

had joined Reno, there was no attacking force of Indians in the vicinity, and he

had at his disposal two-thirds of Custer's entire regiment, as well as the

easily accessible reserve ammunition. Gen. Nelson A. Miles, in his Personal

Recollections, found no reason for

Benteen's

failure to go to Custer's relief. He asserted, after an examination of the

battlefield, that a gallop of fifteen minutes would have brought reinforcements

to Custer. Miles's

opinion contributes to the mystery of why, for more than an hour—while Custer's

command was being overwhelmed—Reno and

Benteen

remained inactive.

Bibliography

|

Following the war, Custer was appointed first lieutenant in the 7th

Cavalry in 1866. He was wounded in the Washita campaign of the Indian

Wars, in 1868. He later served on Reconstruction duty in South Carolina

and participated in the Yellowstone Expedition of 1873 and the Black Hills

Expedition of 1874. He was appointed captain in 1875 and given command of

Company C of the 7th Cavalry. Custer participated in the arrest of the

Lakota Rain-in-the-Face for murder at the trading post at Standing Rock

Agency.

During the 1876 Little Bighorn campaign of the Black Hills War, he served

as aide-de-camp to Lt. Col. George A. Custer and died with his brother.

Lt. Henry Harrington actually led Company C during the battle. Younger

brother Boston Custer also died in the fighting, as did other Custer

relatives and friends. It was widely rumored that Rain-in-the-Face, who

had escaped from captivity and was a participant at the Little Bighorn,

had cut out Tom Custer's heart as revenge. This tale seems apocryphal.

However, Custer's body was badly mutilated post-mortem. His remains were

identified by a recognizable tattoo of his initials on his arm.

|

Tom Custer was buried on the battlefield, but exhumed the next year and

reburied in Fort Leavenworth National Cemetery. A stone memorial slab marks

the place where his body was discovered and initially buried.

|

Little Bighorn, battle of (1876), second defeat (the first was of Crook's

column at the Rosebud on 17 June) of an attempt by the US army to trap

rebellious Lakota and Arapaho/Cheyenne on their Montana hunting grounds. On 25

June Custer sent part of his 7th Cavalry under Reno to ‘beat’ the hostiles out

of their encampment, while led by Crow scouts he hooked around to drive off

their pony herd and envelop them, a standard Indian-fighting tactic. On 25 June

he was outmanoeuvred and his detachment of 215 men was annihilated between an

anvil led by the Hunkpapa Gall that cut off his retreat and a head-on mounted

hammer led by the Oglala Crazy Horse. The rest of the regiment lost a further

100 men when Reno was forced back upon the reserve elements under Benteen in the

hills along Custer's line of advance, where they were besieged for 36 hours.

Coming nine days before the centenary of the USA, the battle immediately assumed

mythic status and it is probably the most written-about skirmish in military

history. The lonely battlefield, with poignant white markers showing where

Custer's men fell, is among the most visited US National Parks.

Battle of the Little Bighorn

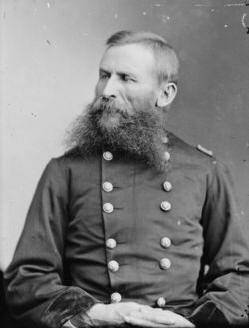

George Armstrong Custer (December 5, 1839 – June 25, 1876) was a United States

Army officer and cavalry commander in the American Civil War and the Indian

Wars. At the start of the Civil War, Custer was a cadet at the United States

Military Academy and his class's graduation was accelerated so that they could

enter the war; Custer graduated last in

his class. He served at the First

Battle of Bull Run and was a staff officer for Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan

in the Army of the Potomac's 1862 Peninsula Campaign. Early in the

Gettysburg Campaign, Custer's association with cavalry commander Maj. Gen.

Alfred Pleasonton earned him promotion from first lieutenant to brigadier

general of United States Volunteers at the age of 23.[1]

Custer established a reputation as an aggressive cavalry brigade commander

willing to take personal risks by leading his Michigan Brigade into battle, such

as the mounted charges at Hunterstown and East Cavalry Field at the Battle of

Gettysburg. In 1864, with the Cavalry Corps under the command of Maj. Gen.

Philip Sheridan, Custer led his "Wolverines", and later a division, through the

Overland Campaign, including the Battle of Trevilian Station, where Custer was

humiliated by having his division trains overrun and his personal baggage

captured by the Confederates. Custer and Sheridan defeated the Confederate army

of Lt. Gen. Jubal A. Early in the Valley Campaigns of 1864. In 1865, Custer

played a key role in the Appomattox Campaign, with his division blocking Robert

E. Lee's retreat on its final day.[2]

At the end of the Civil War (April 15,

1865), Custer was promoted to major general of United States Volunteers.[1]

In 1866, he was appointed to the regular army position of lieutenant colonel of

the 7th U.S. Cavalry and served in the Indian Wars. He was defeated and killed

at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in 1876, against a coalition of Native

American tribes composed almost exclusively of Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho

warriors, and led by the Sioux chiefs Crazy Horse and Gall and by the Hunkpapa

seer and medicine man, Sitting Bull. This confrontation has come to be popularly

known in American history as Custer's Last Stand.

[edit] Birth and family

Custer was born in New

Rumley,

Ohio, to Emanuel Henry Custer (1806-1892), a farmer and blacksmith, and

Marie Ward Kirkpatrick (1807-1882).[3] Throughout his life Custer was known by a

variety of nicknames. He was called alternately Autie (his early attempt to

pronounce his middle name) and Armstrong. The names Curley and Jack (a phonetic

name for his initials GAC which was on his satchel) were used by his troops.

When he went west, the Plains Indians called him Yellow Hair and Son of the

Morning Star. His brothers Thomas Custer and Boston Custer died with him at the

Battle of the Little Big Horn, as did his brother-in-law, James Calhoun, and

nephew, Autie Reed. His other full siblings were Nevin Custer and Margaret

Custer; he also had several older half-siblings.

The Custer family had emigrated to America in the late 17th century from

Westphalia, Germany. Their surname

originally was "Küster".

George Armstrong Custer was a great great grandson of Arnold Küster from

Kaldenkirchen, Duchy of Jülich (today North Rhine-Westphalia state), who settled

in Hanover, Pennsylvania.

Custer's mother's maiden name was Marie Ward. At the age of 16, she married

Israel Kirkpatrick, who died in 1835. She married Emanuel Henry Custer in 1836.

Marie's grandparents, George Ward (1724-1811) and Mary Ward (nee Grier)

(1733-1811), were from County Durham, England. Their son James Grier Ward

(1765-1824) was born in Dauphin, Pennsylvania and married Catherine Rogers

(1776-1829), and their daughter, Marie Ward, was Custer's mother. Catherine

Rogers was a daughter of Thomas Rogers and Sarah Armstrong. According to family

letters in The Custer Story, Custer was named after George Armstrong, a

minister, in the hopes of his devout father that his son might become part of

the clergy.

[edit] Early life

USMA Cadet George Armstrong "Autie" Custer, ca. 1859Custer spent much of his

boyhood living with his half-sister and his brother-in-law in Monroe, Michigan,

where he attended school and is now honored by a statue in the center of

town.[4] Before entering the United States Military Academy, Custer attended the

McNeely Normal School, later known as Hopedale Normal College, in Hopedale, Ohio

and known as the first coeducational college for teachers in eastern Ohio. While

attending Hopedale, Custer, together with classmate William Enos Emery, was

known to have carried coal to help pay for their room and board. Custer

graduated from McNeely Normal School in 1856 and taught school in Ohio.

Custer was graduated a year early, last in the Class of 1861 from the United

States Military Academy, just after the start of the Civil War.[5] Ordinarily,

such a showing would be a ticket to an obscure posting and career, but he had

the fortune to graduate just as the war caused the army to experience a sudden

need for new officers. His tenure at the academy was a rocky one and he came

close to expulsion each of his four years due to excessive demerits, many from

pulling pranks on fellow cadets. His distinguished war record, which started

with riding dispatches for General Scott, has been overshadowed in history by

his role and fate in the Indian Wars.

[edit] Civil War

[edit] McClellan and Pleasonton

Second Lieutenant George Custer (right) with captured Confederate Lieutenant

Washington, at Fair Oaks, 1862 (Library of Congress)Custer was commissioned a

second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry and immediately joined his regiment at

the First Battle of Bull Run, where Army commander Winfield Scott detailed him

to carry messages to Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell. After the battle he was

reassigned to the 5th U.S. Cavalry, with which he served through the early days

of the Peninsula Campaign in 1862. During the pursuit of Confederate General

Joseph E. Johnston up the Peninsula, on May 24, 1862, Custer persuaded a colonel

to allow him to lead an attack with four companies of Michigan infantry across

the Chickahominy River above New Bridge. The attack was successful, capturing 50

Confederates. Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the

Potomac, termed it a "very gallant affair", congratulated Custer personally, and

brought him onto his staff as an aide-de-camp with the temporary rank of

captain. In this role, Custer began his lifelong pursuit of publicity. On one

occasion when McClellan and his staff were reconnoitering a potential crossing

point on the Chickahominy River, they stopped and Custer overheard his commander

mutter to himself, "I wish I knew how deep it is." Custer dashed forward on his

horse out to the middle of the river and turned to the astonished officers of

the staff and shouted triumphantly, "That's how deep it is, General!"

Custer (extreme right) with President Lincoln, George B. McClellan and other

officers at the Battle of Antietam, 1862When McClellan was relieved of command

in November 1862, Custer reverted to the rank of first lieutenant. Custer fell

into the orbit of Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton, who was commanding a cavalry

division. The general was Custer's

introduction to the world of extravagant uniforms and political maneuvering and

the young lieutenant became his protégé, serving on

Pleasonton's

staff while continuing his assignment with his regiment. Custer was quoted as

saying that "no father could love his son more than General Pleasonton

loves me." After the Battle of Chancellorsville, Pleasonton became the commander

of the Cavalry Corps of the Army of the Potomac and his first assignment was to

locate the army of Robert E. Lee, moving north through the Shenandoah Valley in

the beginning of the Gettysburg Campaign. In his first command, Custer affected

a showy, personalized uniform style that alienated his men, but he won them over

with his readiness to lead attacks (a contrast to the many officers who would

hang back, hoping to avoid being hit); his men began to adopt elements of his

uniform customization. Custer distinguished himself by fearless, aggressive

actions in some of the numerous cavalry engagements that started off the

campaign, including Brandy Station and Aldie.

[edit] Brigade command and Gettysburg

Captain Custer (left) with General Alfred Pleasonton (right) on horseback in

Falmouth, Virginia.On June 28, 1863, three days prior to the Battle of

Gettysburg, General Pleasonton promoted Custer from lieutenant to brigadier

general of volunteers.[1][6] Despite having no direct command experience, he

became one of the youngest generals in the Union Army at age 23. Two

captains—Wesley Merritt and Elon J. Farnsworth—were promoted along with Custer,

although they did have command experience. Custer lost no time in implanting his

aggressive character on his brigade, part of the division of Brig. Gen. Judson

Kilpatrick. He fought against the Confederate cavalry of J.E.B. Stuart at

Hanover and Hunterstown, on the way to the main event at Gettysburg.

Custer's style of battle was often

claimed to be reckless or foolhardy, but military planning was always the

basis of every Custer "dash". As the Custer Story in Letters explained, "George

Custer meticulously scouted every battlefield, gauged the enemies weak points

and strengths, ascertained the best line of attack and only after he was

satisfied was the "Custer Dash" with a Michigan yell focused with complete

surprise on the enemy in routing them every time. One of his greatest attributes

during the Civil War was what Custer wrote of as "luck" and he needed it to

survive some of these charges.

At Hunterstown, in an ill-considered charge ordered by Kilpatrick against the

brigade of Wade Hampton, Custer fell from his wounded horse directly before the

enemy and became the target of numerous enemy rifles. He was rescued by the

bugler of the 1st Michigan Cavalry, Norville Churchill, who galloped up, shot

Custer's nearest assailant, and allowed Custer to mount behind him for a dash to

safety.

One of many of Custer's finest hours in the Civil War was just east of

Gettysburg on July 3, 1863. In conjunction with Pickett's Charge to the west,

Robert E. Lee dispatched Stuart's cavalry on a mission into the rear of the

Union Army. Custer encountered the Union cavalry division of David McM. Gregg,

directly in the path of Stuart's horsemen. He convinced Gregg to allow him to

stay and fight, while his own division was stationed to the south out of the

action. At East Cavalry Field, hours of charges and hand-to-hand combat ensued.

Custer led a mounted charge of the 1st Michigan Cavalry, breaking the back of

the Confederate assault. Custer's brigade lost 257 men at Gettysburg, the

highest loss of any Union cavalry brigade.[7] For this General Custer and the

division were given the honor of leading the army on point after the

battle.[citation needed]

[edit] Marriage

George and Libbie Custer, 1864Custer married Elizabeth Clift Bacon (1842–1933)

on February 9, 1864. She was born in Monroe, Michigan, to Daniel Stanton Bacon

and Eleanor Sophia Page.[citation needed] Following the Battle of Washita River

in November 1868, Custer was alleged (by Captain Frederick Benteen, chief of

scouts Ben Clark, and Cheyenne oral tradition) to have had a sexual relationship

during the winter and early spring of 1868-1869 with Monaseetah, daughter of the

Cheyenne chief Little Rock (killed in the Washita battle).[8] Monahsetah gave

birth to a child in January 1869, two months after the Washita battle; Cheyenne

oral history also alleges that she bore a second child, fathered by Custer, in

late 1869.[8]

[edit] The Valley and Appomattox

When the cavalry corps of the Army of the Potomac was reorganized under Philip

Sheridan in 1864, Custer took part in the various actions of the cavalry in the

Overland Campaign, including the Battle of the Wilderness (after which he

ascended to division command), the Battle of Yellow Tavern, where Jeb Stuart was

mortally wounded, and the Battle of Trevilian Station, where Custer was

humiliated by having his division trains overrun and his personal baggage

captured by the Confederates. When Confederate General Jubal A. Early moved down

the Shenandoah Valley and threatened Washington, D.C., Custer's division was

dispatched along with Sheridan to the Valley Campaigns of 1864. They pursued the

Confederates at Winchester and effectively destroyed Early's army during

Sheridan's counterattack at Cedar Creek.

Brevet Major General George Armstrong Custer, US Army, 1865Custer and Sheridan,

having defeated Early, returned to the main Union Army lines at the Siege of

Petersburg, where they spent the winter. In April 1865 the Confederate lines

were finally broken and Robert E. Lee began his retreat to Appomattox Court

House, pursued by the Union cavalry. Custer distinguished himself by his actions

at Waynesboro, Dinwiddie Court House, and Five Forks. His division blocked Lee's

retreat on its final day and received the first flag of truce from the

Confederate force. Custer was present at the surrender at Appomattox Court House

and the table upon which the surrender was signed was presented to him as a gift

for his gallantry. Before the close of the war Custer received brevet promotions

to brigadier and major general in the Regular Army and major general in the

volunteers. As with most wartime promotions, these senior ranks were only

temporary.

[edit] Indian Wars

Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer, 7th

U.S. Cavalry, ca. 1875On February 1, 1866, Custer was mustered out of the

volunteer service and returned to his permanent rank of captain in the Regular

Army, assigned to the 5th U.S. Cavalry. Custer took an extended leave,

exploring options in New York City,[9] where he considered careers in railroads

and mining.[10] Offered a position as adjutant general of the army of Benito

Juárez of Mexico, who was then in a struggle with Maximilian, Custer applied for

a one-year leave of absence from the U.S. Army, but his appointment was blocked

by U.S. Secretary of State William H. Seward, who feared offending France.[10]

Following the death of his father-in-law in May 1866,

Custer returned to Monroe, Michigan,

where he considered running for Congress and took part in public discussion over

the treatment of the American South in the aftermath of the Civil War,

advocating a policy of moderation.[10] In September 1866 he accompanied

President Andrew Johnson on a train journey to build up public support for

Johnson's policies towards the South. Custer denied a charge by the newspapers

that Johnson had promised him a colonel's commission in return for his support,

though Custer had written to Johnson some weeks before seeking such a

commission.[11]

Custer was offered command of the U.S. 10th Cavalry Regiment (otherwise known as

the Buffalo Soldiers)[12][citation needed], a position with the permanent rank

of full colonel, but turned the command down in favor of a lieutenant colonelcy

of the newly created U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment,[13] headquartered at Fort Riley,

Kansas.[14] As a result of a plea by his patron General Philip Sheridan, Custer

was also recipient of a brevet rank of major general.[13] He then took part in

General Winfield Scott Hancock's expedition against the Cheyenne in 1867.

His career took a brief detour following

the Hancock campaign when he was court-martialed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas for

being AWOL, after abandoning his post to see his wife, and was suspended for

duty for one year. He returned to duty in 1868, before his term of

suspension had expired, at the request of General Philip Sheridan, who wanted

Custer for his planned winter campaign against the Cheyenne.

Under Sheridan's orders, Custer took part in establishing Camp Supply in Indian

Territory in early November 1868 as a supply base for the winter campaign.

Custer then led the 7th U.S. Cavalry in an attack on the Cheyenne encampment of

Black Kettle - the Battle of Washita River on November 27, 1868. Custer reported

killing 103 warriors, though estimates by the Cheyenne themselves of the number

of Indian casualties were substantially lower; some women and children were also

killed, and 53 women and children were taken prisoner. Custer had his men shoot

most of the 875 Indian ponies the troops had captured. This was regarded as the

first substantial U.S. victory in the Indian Wars, helping to force a

significant portion of the Southern Cheyennes onto a U.S. appointed reservation.

In 1873, he was sent to the Dakota

Territory to protect a railroad survey party against the Sioux. On August 4,

1873, near the Tongue River, Custer and the 7th U.S. Cavalry clashed for the

first time with the Sioux. Only one man on each side was killed. In 1874, Custer

led an expedition into the Black Hills and announced the discovery of gold on

French Creek near present-day Custer, South Dakota. Custer's announcement

triggered the Black Hills Gold Rush and gave rise to the lawless town of

Deadwood, South Dakota.

[edit] Battle of the Little Bighorn

Main article: Battle of the Little Bighorn

An 1899 chromolithograph entitled Custer Massacre at Big Horn, Montana — June

25, 1876, artist unknown.By the time of Custer's expedition to the Black Hills

in 1874, the level of conflict and tension between the U.S. and many plains

Indians tribes (including the Lakota Sioux and the Cheyenne) had become

exceedingly high. Indians killed settlers and railroad workers, white Americans

continually broke treaty agreements and advanced further westward. To take

possession of the Black Hills (and thus the gold deposits), and to stop Indian

attacks, the U.S. decided to corral all remaining free plains Indians. The Grant

government set a deadline of January 31, 1876 for all Lakota and Northern

Cheyenne to report to their designated agencies (reservations) or be considered

a "hostile".

The 7th Cavalry departed from Fort Lincoln on May 17, 1876, part of a larger

army force planning to round up remaining free Indians. Meanwhile, in the spring

and summer of 1876, the Hunkpapa Lakota chief Sitting Bull had called together

the largest ever gathering of plains Indians at Ash Creek, Montana (later moved

to the Little Bighorn River) to discuss what to do about the whites.[15] It was

this united encampment of Lakota, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho Indians that

the 7th met at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

On June 25, some of Custer's Crow Indian scouts identified what they claimed was

a large Indian encampment along the Little Bighorn River.

Custer divided his forces into three

battalions: one led by major Marcus Reno, one by Captain Frederick

Benteen,

and one by himself. Captain Thomas M. McDougall and Company B were with the pack

train. Benteen was sent south and west, to cut off any attempted escape

by the Indians, Reno was sent north to charge the southern end of the

encampment, and Custer rode north, hidden to the east of the encampment by

bluffs, and planning to circle around and attack from the north.[16][17]

Reno began a charge on the southern end

of the village, but halted midway and had his men dismount and form a skirmish

line.[18][17] They were soon overcome by the Lakota and Cheyenne warriors who

counterattacked en masse,[19] forcing Reno and his men to take cover in

the trees along the river. Eventually, however, this position became untenable

and the troopers were forced into a bloody retreat up onto the bluffs above the

river, where they made their own stand.[20][21] This, the opening action of the

battle, cost Reno a quarter of his command.

Meanwhile, unaware of Reno's failure, Custer had led his command to the northern

end the main encampment, where he apparently planned to sandwich the Indians

between his attacking troopers and Reno's command. According to Grinnell's

account, based on the testimony of the Cheyenne warriors who survived the

fight,[22] at least part of Custer's command attempted to ford the river at the

north end of the camp but were driven off by stiff resistance from the Indians

and were pursued by hundreds of warriors onto a ridge north of the encampment.

There, Custer was prevented from digging

in by Crazy Horse, whose warriors had outflanked him and were now to his north,

at the crest of the ridge.[23] Traditional white accounts attribute to

Gall the attack that drove Custer up onto the ridge, but Indian witnesses have

disputed that account.[24] For a time, Custer's men were deployed by company, in

standard cavalry fighting formation--the skirmish line, with every fourth man

holding the horses. This arrangement, however, robbed Custer of a quarter of his

firepower, and as the fight intensified, many soldiers took to holding their own

horses or hobbling them, further reducing their effective fire. When Crazy Horse

and White Bull mounted the charge that broke through the center of Custer's

lines, pandemonium broke out among the men of Calhoun's command,[25] though

Keogh's men seem to have fought and died where they stood. Many of the panicking

soldiers threw down their weapons[26] and either rode or ran towards the knoll

where Custer, the other officers, and about 40 men were making a stand. Along

the way, the Indians rode them down, counting coup by whacking the fleeing

troopers with their quirts or lances.[27]

Initially, Custer had 208 officers and men under his command, with an additional

142 under Reno and just over a hundred under Benteen. The Indians fielded over

1800 warriors,[28] although historically, the numbers do seem to have been

exaggerated to explain Custer's defeat, and again, to exculpate him from his

numerous errors before and during the battle. As the troopers were cut down,

moreover, the Indians stripped the dead of their firearms and ammunition, with

the result that the return fire from the cavalry steadily decreased, while the

fire from the Indians steadily increased. With Custer and the survivors shooting

the remaining horses to use them as breastworks and making a final stand on the

knoll at the north end of the ridge, the Indians closed in for the final attack

and killed all in Custer's command. As a result, the Battle of the Little

Bighorn has come to be popularly known as "Custer's Last Stand".

When the cavalry's main column did

arrive three days later, they found most of the soldiers' corpses stripped,

scalped, and mutilated.[29] Custer’s body had two bullet holes, one in the left

temple and one just above the heart.[30] Following the recovery of Custer's

body, he was given a funeral with full military honors, and was buried on the

battlefield, and later reinterred

in the West Point Cemetery on October 10, 1877. The site of the battle was

designated a National Cemetery in 1876.

[edit] Controversial legacy

George A. Custer in civilian clothes, ca. 1876After his death, Custer achieved

the lasting fame that eluded him in life. The public saw him as a tragic

military hero and gentleman who sacrificed his life for his country. Custer's

wife, Elizabeth, who accompanied him in many of his frontier expeditions, did

much to advance this view with the publication of several books about her late

husband: Boots and Saddles, Life with General Custer in Dakota (1885), Tenting

on the Plains (1887), and Following the Guidon (1891). General Custer himself

wrote about the Indian wars in My Life on the Plains (1874) and was the

posthumous co-author of The Custer Story (1950).

Today Custer would be called a "media personality" who understood the value of

good public relations and leveraged media effectively; he frequently invited

correspondents to accompany him on his campaigns, and their favorable reportage

contributed to his high reputation that lasted well into the 20th century.

After being promoted to brigadier general, Custer sported a uniform that

included shiny jackboots, tight olive corduroy trousers, a wide-brimmed slouch

hat, tight hussar jacket of black velveteen with silver piping on the sleeves, a

sailor shirt with silver stars on his collar, and a red cravat. He wore his hair

in long glistening ringlets liberally sprinkled with cinnamon-scented hair oil.

Later in his campaigns against the Indians, Custer wore a buckskin outfit along

with his familiar red tie.

The assessment of Custer's actions during the Indian Wars has undergone

substantial reconsideration in modern times[citation needed]. For many critics,

Custer was the personification of the U.S. Government's ill-treatment of the

Native American tribes, while others see him as a scapegoat for the Grant Indian

policy, which he personally opposed.[citation needed] His testimony on

behalf of the abuses sustained by the

reservation Indians nearly cost him his command by the Grant

administration. Custer once wrote that if he were an Indian, he would rather

fight for his freedom alongside the hostile warriors "than be confined to the

limits of a reservation".[citation needed]

Many criticized Custer's actions during the battle of the Little Bighorn,

claiming his actions were impulsive and foolish,[citation needed] while others

praised him as a fallen hero who was betrayed by the incompetence of his

subordinate officers.[citation needed]

The controversy over who is to blame for the disaster at Little Bighorn

continues to this day. Critics at the time through the present have asserted at

least three military blunders. First, Custer refused the support offered by

General Terry on 21 June of an additional battalion. At the same time, he left

behind at the steamer Far West on the Yellowstone a battery of

Gatling

guns, knowing he was facing superior numbers. Finally, on the day of the battle,

he divided his 600-man command in the face of superior numbers. Certainly

reducing the size of his force by at least a sixth, and rejecting the firepower

offered by the Gatling

guns played into the events of 25 June to the disadvantage of the 7th

cavalry.[31]

[edit] Monuments and memorials

Custer Memorial at his birthplace in New Rumley, Ohio* Counties are named in

Custer's honor in five states: Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, Oklahoma and South

Dakota. Custer County, Idaho, is named for the General Custer mine, which, in

turn, was named after Custer. There are several townships named for Custer in

Minnesota and Michigan. There are also the towns of Custer, Michigan, Custer,

South Dakota, Custar, Ohio, and the unincorporated town of Custer, Wisconsin. A

portion of Monroe County, Michigan, is informally referred to as "Custerville."

[1]

Custer National Cemetery is within Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument,

the site of Custer's death.

There is an equestrian statue of Custer in Monroe, Michigan, his boyhood home.

Originally located near city hall, in the center of town, it was moved years

later to Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Park, a small park near the River Raisin

and away from the main thoroughfares of the city. Due to lobbying by Libbie

Custer and others, it was eventually moved to its current location, on the

corner of Monroe and Elm Streets, on the edge of downtown Monroe.

Fort Custer National Military Reservation, near Augusta, Michigan, was built in

1917 on 130 parcels of land, mainly small farms leased to the government by the

local chamber of commerce as part of the military mobilization for World War I.

During the war, some 90,000 troops passed through Camp Custer. Following the

Armistice of 1918, the camp became a demobilization base for over 100,000 men.

In the years following World War I, the camp was used to train the Officer

Reserve Corps and the Civilian Conservation Corps. On August 17, 1940, Camp

Custer was designated Fort Custer and became a permanent military training base.

During World War II, more than 300,000 troops trained there, including the famed

5th Infantry Division (also known as the "Red Diamond Division") which left for

combat in Normandy, France, June 1944. Fort Custer also served as a prisoner of

war camp for 5,000 German soldiers until 1945. Today Fort Custer's training

facilities are used by the Michigan National Guard and other branches of the

armed forces, primarily from Ohio, Illinois, and Indiana. Many Reserve Officer

Training Corps (ROTC) students from colleges in Michigan, Ohio, Illinois, and

Indiana also train at this facility, as well as do the FBI, the Michigan State

Police, and various other law enforcement agencies. (https://www.mi.ngb.army.mil/ftcuster/default.asp)

The establishment of Fort Custer National Cemetery (originally Fort Custer Post

Cemetery) took place on September 18, 1943, with the first interment. As early

as the 1960s, local politicians and veterans organizations advocated the

establishment of a national cemetery at Fort Custer. The National Cemeteries Act

of 1973 directed the Veterans' Administration to develop a plan to provide

burial space to all veterans who desired interment in a national cemetery. After

much study, the NCS adopted what became the regional concept. Fort Custer became

the Veterans' Administration's choice for its Region V national cemetery. Toward

this goal, Congress created Fort Custer National Cemetery in September 1981. The

cemetery received 566 acres from the Fort Custer Military Reservation and 203

acres from the VA Medical Center. The first burial took place on June 1, 1982.

At the same time, approximately 2,600 gravesites were available in the post

cemetery, which made it possible for veterans to be buried there while the new

facility was being developed. On Memorial Day 1982, more than 33 years after the

first resolution had been introduced in Congress, impressive ceremonies marked

the official opening of the cemetery.(http://www.cem.va.gov/nchp/ftcuster.htm)

Custer Hill is the main troop billeting area at Fort Riley, Kansas.

The US 85th Infantry Division was nicknamed The Custer Division.

The Black Hills of South Dakota is full of evidence of Custer, with a county,

town, and the Custer State Park all located in the area.

Custer Observatory is the oldest observatory on Long Island. Located in

Southold, New York, it was founded in 1927 by Charles Elmer (co-founder of the

Perkin-Elmer Optical Company ), along with a group of fellow

amateur-astronomers. This name was chosen to honor the hospitality of Mrs.

Elmer, formerly May Custer, the Grand Niece of General George Armstrong Custer.

[edit] See also

Custer’s last stand and defeat is one of

the most famous military blunders in history, yet compared with most

events in military history it is a very small affair with a mere 250 dead, but

it is as well known to most people as the D Day landings, or the battle of

Waterloo. Custer was born 5th December 1839 near New Rumley Ohio and entered the

West Point military academy in July 1857.

In a shadow of things to come his West Point career was filled with demerits and

near dismissals. With many of his class mates heading south for

commissions in the Confederate cause (American Civil War) he passed out last in

his class of 34 in June 1861 and was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant in the US

2nd Cavalry.

Civil War service

George Armstrong Custer

He was present at the First Battle of Bull Run but did not see action. He

transferred in August to the 5th Cavalry and was promoted to a 1st Lieutenant in

July 1862. Since the June he had been an aide to General McClellan with the

acting rank of captain and he remained as the Generals aide until March 1863.

In June 1863 he was made

Brigadier-General of volunteers while he was only 23. He distinguished

himself while in command of the Michigan Cavalry Brigade at the battle of

Gettysburg and leading a cavalry charge 2 days later with the 7th Michigan

Cavalry. In typical Custer style he described this by saying “ I challenge the

annals of war to produce a more brilliant charge of cavalry” Custer served with

the Army of the Potomac throughout 1864 and gained further renown during the

battles of the Shenandoah Valley. He ended the civil war as a major general of

volunteers leading a cavalry division. He was an over the top character who

loved publicity and gained more than other more accomplished officers, the press

for their part loved him a young showman with long red hair and a taste for

velvet jackets with gold braid he would not have been out of place in Napoleon's

cavalry of half a century earlier.

Already he was autocratic and a dictatorial leader, who had risen so quickly

through the ranks he had had little time to learn from his mistakes, although

his incredible arrogance would have probably prevented him

recognising

any mistakes as his own.

Post War service

Custer’s first post war command ended when his

Michigan Cavalry was disbanded after a

mutiny, which was partly caused by his heavy-handed discipline. Many

volunteer units were pushing for disbandment but Custer had reintroduced the

lash as a form of discipline. He

mustered out of voluntary service in Feb 1866 and reverted to his army rank of

captain but he still liked to be referred to as General Custer. He made

some moves to becoming the Commander of the Mexican cavalry and was offered but

refused command of the 9th Negro Cavalry and in July 1866 took command as a

Lt-Colonel of the newly formed 7th Cavalry, its Colonels being mainly on

detached duties.

In early 1867 while on a recon mission Custer’s behaviour led to a courts

martial and he was found guilty of absenting himself from his command, and using

some troopers as an escort while on unofficial business, abandoning two men

reported killed on the march and failing to pursue the Indians responsible,

failing recover the bodies, and ordering a party going after deserters to shoot

to kill which resulted in 1 death and 3 wounded, and finally unjustifiable

cruelty to those wounded. He was sentenced to suspension from rank and pay for a

year, but a lack of a replacement meant he was returned to duty early. The

incident caused much bad feeling among the regiment’s officers for several

years. The regiment saw minor skirmishes against the native Indians for the next

few years. Custer didn’t see any action but published exaggerated accounts of

the 7th cavalry’s actions.

Squaw Killer

In November 1868 the 7th cavalry

fought at the battle of Washita during which over a hundred Indians were killed

including some women and children which the Cheyenne nicknamed Custer ‘Squaw

killer” for. Custer’s incompetence led to some deaths during the

campaign, which also increased ill feeling towards him.

In spring 1873 the Regiment was moved to Dakota under command of Col D.S Stanley

at fort Rice. While protecting some

railway engineers the regiment skirmished with local Indians and during these

Custer was charged with insubordination but his friends persuaded the Col to

drop the charges. In 1874 a ‘Scientific’ expedition was sent to the Black

Hill country with Custer leading the escort of ten companies of the 7th, some

infantry and scouts and a detachment of Gatling guns. He was charged with recon

of a site for a new fort by the size of his force suggests another agenda. Some

have accused Custer of spreading stories of a gold find and although the force

was too strong the Indians attacked the gaggle of lawless prospectors that

followed. In 1875 the government tried to get the Indians to sell the area but

by 1876 this had been abandoned and a military campaign was planned. The attacks

on the trespassing prospectors were used as an excuse and the campaign was under

General A Terry with Custer commanding the whole of the

7th Cavalry 600 men.

Custer had command only because of Terry’s support; he was in disgrace again

having offended President (former General) Grant, Army Commander General William

Sherman and his division commander Sheridan.

The allegations are complex but

centred

around irregularities in trading post allocation. Custer always looking

for publicity had repeated rumours and hearsay to the press but was found to

know nothing under oath. The battle of Little Big Horn will be covered in detail

elsewhere but basically Custer was ordered specifically to continue south to

prevent any break out of Indian forces under Crazy horse as two main armies

tried to trap them. On 24th June Custer found the enemies trail lead towards

Little Big Horn and typically he choose not to follow orders. On the 25th he

could see the Indians in the valley below probably around 15,000 strong, he then

decided to split his force into 3 and attack the encampment from three

directions. Considering the size of the enemy force this was pure lunacy.

The other two parts of his attack were

driven back but made it to the safety of high ground to be relieved by the main

force the next day. Custer’s force was cut off and slaughtered by Crazy

Horse’s Sioux.

Total incompetent and sycophant

Custer’s actions that day were

typical of one of the worse commanders in history, and typical of his glory

seeking, arrogant incompetent character. He had risen to a position of power due

to friends and supporters at a time when in the aftermath of the American Civil

war the press wanted a hero and the Army had a shortage of good commanders.

Custer would have been pleased his name went down in history but this is little

comfort to the families of those that died to serve his glory.

The Approaching Clouds of War

Early in June Crook's company was on the northeast slope of the Big Horn, and

General Sheridan, planning the entire operation, saw with fear that large

numbers of Indians were daily leaving the reservations south of the Black Hills

and going around General Crook to join Sitting Bull. The Fifth Regiment of

Cavalry was sent from Kansas to Cheyenne, and marched rapidly to the Black Hills

to cut off these reinforcements. The great mass of the Indians lay between Crook

at the head waters of Tongue River and Terry and Gibbon near its mouth,

completely stopping all communications between the commanders. They harassed

Crook's outposts and supply trains, and by June Crook decided to engage them and

see the strength of their force. On June 17th Crook skirmished with the Sioux on

the bluffs of the Rosebud. He had several hundred Crow allies. The combat lasted

much of the day; but long before it was half over Crook was on the defensive and

was actually withdrawing his men. He had found a hornets' nest, and knew it was

too much for his small command. Pulling out as best he could, he fell back to

the Tongue, sent for the entire Fifth Cavalry and all available infantry, and

rested until they could reach him. Crook had not managed to even get within site

of Sitting Bull's Great Indian Village.

Meantime Terry and Gibbon sent their scouts up stream. Major Reno, with a strong

battalion of the Seventh Cavalry, left camp to scout up the Wolf Mountains.

Sitting Bull and his people decided it was time to move. Their camp stretched

for six miles, and their thousands of horses had eaten all the grass. While they

had been victorious, they decided it was time to move to the valley of the

Little Big Horn. Marching up the Rosebud, Major Reno was confronted by the sight

of an immense trail turning suddenly west and crossing the great divide over

toward the west. Experienced Indian fighters in his command told him that

thousands of Indians had crossed that way within the last few days. Reno wisely

turned back, and reported what he had seen to Terry.

Enter George Armstrong Custer

At the head of Terry's cavalry was Brevet Major-General George Armstrong Custer,

a daring, dashing, impetuous soldier, who had won high honors as a division

commander during the Civil War, and who had developed a reputation as an Indian

Fighter when he led his gallant regiment against the

Kiowas

and the Cheyennes

on the Southern plains. Custer had entered the Sioux country two times in recent

campaigns. While Custer no doubt had experience, there were those who were

superiors and subordinates who feared that Custer lacked the judgment needed to

face a man like Sitting Bull on the Battlefield.

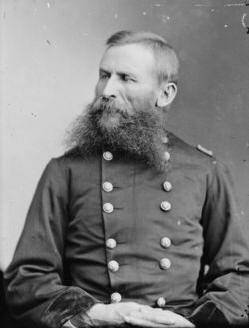

General George A. Custer, Commanding the 7th Cavalry at Little Big Horn

Custer had experienced conflict with both his commanders in the Dakota

Department, and within his regiment. It is clear, however, that everyone honored

his bravery and daring.

Some have speculated that the flamboyant Custer was considering a bid for the

presidency, and that he sought one more bold and dramatic victory to secure his

future.

When General Terry decided to send his

cavalry to "scout the trail" reported by Reno, Custer was given command of the

expedition.

Terry concluded that the Sioux had moved their camp across the Little Big Horn

Valley, and he planned to send Custer to hold them from the east, while he and

Gibbon's troops pushed up the Yellowstone in boats. He would then march

southward until he reached Sitting Bull's flank.

Terry's orders to Custer showed an unusual combination of anxiety and tolerance.

He seems to have feared that Custer would be impetuous, but he resisted issuing

an order that might wound the high spirited commander of the 7th Cavalry. Terry

warned Custer to keep watch well out toward his left as he rode westward from

the Rosebud, in order to prevent the Sioux from moving southeastward between the

column and the Big Horn Mountains. He would not impede him with distinct orders

as to what he must or must not do when he came in contact with the warriors, but

he named the 26th of June as the day on which he and Gibbon would reach the

valley of the Little Big Horn, and it was his hope and expectation that Custer

would come up from the east about the same time, and between them they would be

able to soundly whip the assembled Indians.

Custer let him down in an unexpected way. He got there a day ahead of time, and

had ridden night and day to do it. Men and horses were exhausted when the

Seventh Cavalry rode into sight of the Indian Village on the Little Big Horn

that cloudless Sunday morning of the 25th. When Terry came up on the 26th, it

was all over for Custer and his regiment.

Custer started on the trail with the 7th Cavalry, and nothing else. A battalion

of the 2nd was with Gibbon's column; but, luckily for the Second, Custer wanted

none of them. Two field guns were with Terry, but Custer wanted only his own

people. He rode 60 miles in 24 hours. He pushed ahead with focus and without

hesitation. He created an impression

that he wanted to have one dramatic battle with the Indians, in which he and the

Seventh would be the only participants, and hence the heroes. The idea that he

could be defeated apparently never crossed his mind. Custer sought glory, but in

the end, found only infamy.

Crook had over 2,000 men only 30 miles to Custer's left. If Custer had been

scouting as instructed, he would have run into Crook's outposts, and Crook could

have reinforced him. Custer wanted nothing of the sort, and was savoring the

chance to have all the Glory to himself. At daybreak his scouts had come across

two or three warriors killed in the fight of the 17th, and they sent back word

that the valley of the Little Horn was in sight ahead, and there were "signs" of

the Indian Camp.

Pride Comes Before the Fall

Custer then decided to divide his column. He kept 5 companies, commanded by

close friends, with himself. He left Captain McDougal with some troops to guard

the rear. He divided the remaining companies between

Benteen

and Reno. Benteen

was sent two miles to the left, and Reno remained between

Benteen

and Custer. This formed three small columns of 7th cavalry, which moved quickly

westward over the divide.

Custer's troops went into battle with the pomp and parade of war that

distinguished them around their camps. Bright guidons flew in the breeze; many

of the officers and soldiers wore the casual uniform of the cavalry. George

Custer, his brother Tom Custer, Cook and Keogh were all dressed alike in

buckskin jackets and broad rimmed scouting hats, with long leather riding boots.

Captain Yates seemed to prefer his undress uniform, as did most of the

lieutenants in Custer's column.

The brothers Custer and Captain Keogh rode Kentucky Sorrels. The trumpeters were

at the heads of columns, but the band of the Seventh Cavalry had been left

behind. Custer's last charge was started in the absence of the Irish fighting

tunes he loved so dearly.

Following Custer's trail, you will come in sight of the Little Big Horn, snaking

northward to its intersection with the broader stream. Looking southward you

will see the cliffs and canyons of the mountains. To your North, the prairie

reaches the horizon. To your West you see a broad valley on the other side of

the stream. The fatal Greasy Grass is not seen below the steep bluffs that

contain it. The stream comes into sight far to the left front, and comes toward

you bordered by cottonwood and willow trees. It is lost behind the bluffs. For

nearly six miles of its winding course, it can not be seen from where Custer got

his first view of the village. Hundreds of "lodges" that lined its western bank

could not be seen. Custer eagerly scanned the distant tepees that lay far to the

North, and shouted "Custer's luck! The biggest Indian Village on the Continent!"

At this point he could not have seen even 1/3 of the village!

But what he could see was enough to fire the blood of a man like Custer. Huge

clouds of dust, nervous horses, frantic horsemen making a run for it, and down

along the village, lively turmoil an confusion. Tepees were being taken down

quickly, and the women and children were fleeing the carnage that was about to

come. We know now that the men he saw running westward were the young men going

out to round up the horses. We know now that behind those sheltering bluffs were

still thousands of fierce warriors eager and ready to meet George Custer. We

know that the indications of the Indians panicking and retreating was due mainly

to simply trying to get the families away from the fight that was to come. The

warriors were by no means running from the fight, the brave warriors were making

ready for battle!

Custer interpreted this confused scene as the Warring Indians being in full and

speedy retreat. Custer determined that Reno should attack straight ahead, get to

the valley and cross the stream. Reno could then attack the southern end of the

camp. This would leave Custer and his companies to go into the long winding

ravine that ran northwestward to the stream, and then attack aggressively from

the east.

Custer sent a dispatch to Benteen and MacDougall, notifying them of his actions,

and ordering them to hurry back with the pack trains, supplies, and extra

ammunition. Custer placed himself at the

head of his column, and charged down the slope, with his troops close behind.

The last that Reno and his people saw of Custer was the tail of the column

disappearing in a cloud of dust. Then only the cloud of dust could be seen

hanging over the trail.

Moving forward, Reno came quickly to a gully that led down through the bluff to

the stream. A quick run brought him to the ford; his soldiers plunged through,

and began to climb the bank on the western shore. He expected from his orders to

find an unobstructed valley, and five miles away the lodges of the Indian

village. It was with surprise and grave concern that he suddenly rode into full

view of a huge camp, whose southern border was less than two miles away. As far

as he could see, the dust cloud rose above an excited Indian Camp. Herds of war

horses were being run in from the west. Old men, women, children, and ponies

were hurrying off toward the Big Horn. Reno realized that he was in front of the

congregated warriors of the entire Sioux Nation in preparation for battle.

Most people think that Custer expected

Reno to lead a dashing charge into the heart of the Indian Camp, just as Custer

had done at Washita. Reno did not dash as Custer had expected. The sight of the

Assembled Sioux Nation removed any desire Reno had ever had to dash into the

camp. Reno attacked, but the attack was tentative and half-hearted. He

dismounted his men, and advanced them across a mile or so of the prairie.

He fired as he got within range of the village. He did not meet any resistance.

The appearance of Reno's command apparently came as a surprise to the Uncapapa

and Blackfeet, who were on the South side of the camp. The scouts had given sign

of Custer's troops coming down the ravine. Those who had not run for cover were

apparently running toward the Brule village, anticipating that Custer would

strike there first.

Reno could have charged into the south end of the village before his approach

could have been recognized. Instead, he approached slowly on foot. Reno had had

no experience in fighting Indians. He simply concluded that his small column

would not drive the mass of warriors from the valley. In much trepidation, he

sounded a halt, rally, and mount. He then paused, as if he did not know what to

do.

The Indians correctly sensed his hesitation, fear, and indecision. He lost the

element of surprise, he lost his momentum, and he lost the confidence of his own

troops. He emboldened his enemy; "The White Chief was scared"; and now was their

opportunity. Warriors, men and boys, came tearing to the location. A few

well-aimed shots knocked some men off of their horses. Reno quickly ordered a

movement by the flank toward the bluffs across the stream to his right rear. He

never thought to dismount a few cool guns to turn around and cover the enemy. He

placed himself at the new head of column, and

led the retreating movement. Out

came the Indians, with shots and triumphant yells. The rear of the column began

to overtake the head; Reno was walking while the rear was running. The Indians

came dashing up on both flanks and the rear. At this point the poorly led and

helpless troops had no choice. Military

discipline and order were abandoned. In one mad rush they ran for the river,

jumped in, splashed through, and climbed up the steep bluff on the eastern shore

-- an inexcusable panic, due mainly to the incompetent conduct of a cowardly

commander.

Battle Map of the Battle of Little Big Horn

In vain several of the best officers of the column (Donald McIntosh and Benny

Hodgson) tried to rally and protect the rear of the column. The Indians were not

in overpowering numbers at that point, and a bold stand could have saved the

day. But with the Major on the run, the Lieutenants could do nothing, but die

bravely, and in vain. Donald McIntosh was surrounded, knocked from his horse and

butchered. Hodgson, shot off his horse, was rescued by a friend, who dove into

the river with him, but close to the farther shore the Indians killed him, a

bullet tore through his body, the gallant and brave man rolled dead into the

muddy waters.

Once well up the bluffs, Reno's command turned around and considered the

situation. The Indians had stopped their pursuit, and even now were retreating

from range. Reno fired his pistol at the distant warriors in useless defiance of

the men who had stampeded him. He was now up some two hundred feet above them,

and it was as safe as it was harmless. Two of his best men lay dead down on the

banks of the river, and so did more than ten other of his soldiers. The Indians

had swarmed all around his troops, and butchered them as they ran. Many more had

been wounded, but things appeared safe for the moment. The Indians had

mysteriously retreated from their front. Reno did not know what it meant, did

not know what had happened to Custer, and did not know where the commands of

Benteen and MacDougal were.

Over toward the villages, which they could now see stretching for five miles

down the stream, all was total pandemonium and confusion; but northward the

bluffs rose still higher to a point nearly opposite the middle of the villages

-- a point some two miles from them -- and beyond that they could see nothing.

But that is where Custer had gone, and suddenly, splitting through the moist

morning air, came the sound of loud and rapid gunfire; complete volleys followed

by continuous rattle and roar. The sounds of war grew more intense for the next

ten minutes. Some thought they could hear the victory yells of their friends,

and they were ready to yell in reply. Others thought they heard the sound of

"charge" being blown on the trumpets. Many wanted to mount their horses, and

join the fight, which sounded to be just over the bluffs.

But, almost as suddenly as it had started, the sound of gunfire faded away. The

continuous peals of musketry settled into sporadic skirmishing fire. Reno's men

looked at each other in confusion. They could not figure out what had just

happened.

Reno's men were soon encouraged as they heard the reports of scouts that Benteen

and MacDougal were approaching from the east. When they arrived the first thing

they asked was, "Have you seen anything of Custer?"

Benteen and Weir scouted up to a mile or more to the north, had seen swarms of

Indians in the valley below, but not a sign of Custer and his cavalry.

They concluded that there would be no help from Custer, and they did the only

thing they could under these circumstances; they dug in and would try and hold

out until Terry and Gibbon got there. Reno did not have the pack train, which

gave him ample ammunition and supplies.

The question remained, what had happened to George Custer and his men? The

question can only be answered by the Indians who were victorious that day, and

one Indian who had been working for Custer. There was one Crow scout in Custer's

command who managed to escape the carnage of that day in a Sioux blanket.

Between the lone survivor of Custer's command, and the victorious Indian

warriors, a fairly consistent story emerges. From all these sources it was not

hard to trace Custer's every move during that fateful battle.

Custer's Last Stand

Never comprehending the overwhelming odds against him, believing that the

Indians were "on the run", and thinking that between himself and Reno he could

"double them up" in short order, Custer had sealed his fate. It was about five

miles from where Custer first saw the northern end of the village and where he

attacked the center of the village. During this 5 mile ride, Custer never saw

the complete magnitude of the Indian Camp. As he attacked, and rounded the

bluff, he found himself confronted with thousands skilled and well equipped

warriors, all ready for the fight. He

had hoped to attack the center of the village unmolested, and to meet Reno's men

there, coming from the other direction. Instead he faced an intense attack from

the thickets and trees. He could not ignore the attack, and had to deal

with the threat at hand. He had his men dismount, and begin engaging the fire

coming from the thickets. This was a perilous move, as he was outnumbered ten to

one at this point. Worse than that, hundreds of young braves had mounted their

horses and dashed across the river below him, hundreds more were following and

circling all about him. It is likely that this is the point that Custer realized

that he was in trouble, and that he must cut his way out and escape the

overwhelming enemy surrounding him.

His trumpeters sounded "Mount!", and leaving many injured companions on the

ground, the men ran for their mounts. With skill and daring, the Ogalallas and

Brulés recognized the opportunity, and sprang to their horses, and gave chase.

"Make for the heights!" must have been Custer's order, for the first dash was

eastward, and then more to the left as their progress was blocked.

Map of Custer's Last Stand

Then, as Custer and the remainder of his regiments of 7th cavalry reached higher

ground, they must have fully realized the gravity of their situation. For from

this vantage point, all they would have been able to see would be throngs of

skilled Sioux warrior on horseback, circling and laying down a furious fire.

Custer and his command was fully hemmed in, cut off, and losing men quickly.

Custer must have realized that at this point retreat was impossible. Some of the

Indian victors later reported that at this point Custer ordered that the horses

be turned loose, after losing about half of his men.

A skirmish line was then formed down the slope, and there the men fell at 25

feet intervals (It was here that their fellow soldiers found them two days

later). At last, on a mound that stands at the northern end of a little ridge,

Custer, Cook, Yates, Tom Custer, and some dozen other soldiers, (the only white

men left alive at this point), gathered for the last stand. They undoubtedly

fought fiercely, but lost their lives to the superior numbers, and superior

leadership and strategy of the Indian Nation.

Keogh, Calhoun, Crittenden, had all been killed along the skirmish line. Smith,

Porter, and Reily were found dead with the rest of their men. So were the

surgeons, Lord and De Wolf; and, also, were Custer's other brother, "Boston"

Custer and the Herald correspondent.

Two men were not found among the dead. Lieutenants Harrington and Jack Sturgis.

About 30 men had made a run for their lives down a little gully. The banks of

the gully were teamed with Indians, who managed to shoot down the escaping

soldiers as they ran. One officer was reported by the Sioux to have managed to

break through the deadly circle of Indians, the only white man to do so that

day. Five warriors gave chase. It is reported that as the pursuing band was worn

down, and giving up the chase, the officer concluded that all was lost, and took

his pistol, and shot himself in the head. This soldiers skeleton was pointed out

to the officers of the Fifth Cavalry the following year by one of the pursuers.

It had not been found before then. Was it Harrington or could it have been

Sturgis? Some years later yet another skeleton was found even further from the

battle scene. Remnants found at the scene indicated that it was a cavalry

officer. If so, all the missing would be accounted for.

The Sole U.S. Army Survivor

Of the twelve troops of the Seventh Cavalry, Custer led five that hot Sunday

into eternity and infamy at the battle of the Little Big Horn, and of his part

of the regiment only one living thing escaped the deadly skill of the Sioux

warriors. Bleeding from many arrow wounds, weak, thirsty and tired, there came

straggling into the lines some days after the fight Keogh's splendid horse

"Comanche". Who can ever even imagine the scene as the soldiers thronged around

the gallant steed?

Comanche- The only US Army Survivor at the Battle of Little Big Horn.

Editorial Note: There are endless descriptions referring to this horse

"Comanche" as the "only survivor of the Battle of Little Big Horn". Please

remember that there were thousands of brave and victorious survivors among the

Indian Nations. They won the battle and they survived the battle. They were

fighting for their lands, their family, and maybe most of all, for their way of

life. In the end, their cause was lost, and their battle in vain, but we must

remember, and honor their skill, bravery, and honor at this great event in our

history.

As a tribute to his service and bravery, the war horse Comanche was never ridden

again. He was stabled at Fort Riley, and would periodically be paraded by the US

Army. He lived to the age of 29, and when he died his body was mounted and put

on display at the University of Kansas, where it stands to this day.

With Custer's men all dead, the

triumphant Indians left their bodies to be plundered by their women. The

warriors once more focused on Reno's front. There were two nights of celebration

and rejoicing in the Indian Camp, though not one instant was the watch on Reno

eased. All day of the 26th they kept him penned down in his rifle pits. Early on

the morning of the 27th, with great excitement, the lodges were suddenly taken

down, and tribe after tribe, village after village, family after family, six

thousand Indians passed before his eyes, moving towards the mountains.

Terry and Gibbon had arrived. Reno's

small remnant of the 7th cavalry had been saved. Together they reconnoitered the

battlefield, and hastily buried their fallen comrades. They then hurried

back to the Yellowstone while the Sioux were hiding in around the Big Horn. The

Indians were shrewd enough to realize that Crook and Terry would be reinforced.

They also realized that their victory would result in the US Army relentlessly

pursuing them. As they heard that great numbers of troops were assembling near

the Yellowstone and Platte, they took the only reasonable strategy that they

could; the great Alliance of Indian Nations quietly dissolved. Sitting Bull,

with many close associates, made for the Yellowstone, and was driven northward

by General Miles. Others took refuge across the Little Missouri, where Crook

pursued. With much hard pursuit, and even harder fighting, many bands and many

famous chiefs were forced into submission that fall and winter. Among these,

bravest, most skilled, most victorious of all, was the hero of the Powder River

battle, the famed warrior Crazy Horse.

The fame of Crazy Horse, and his

exploits had become the stuff of legends among the Indian camps along the

Rosebud, even before he joined Sitting Bull. He was a key part of the battle

with General Crook on June 17. No chief was as honored or trusted as Crazy

Horse.

Up to the time of Little Big Horn, Sitting Bull had no real claims as a warrior,

or as a war chief. Eleven days before the fight Sitting Bull had a "sun dance."

His own people report that while he was in a trance, he had a vision of his

people being attacked by a large force of white men, and that the Sioux would

enjoy a great victory over them. The battle of the 17th of June was a partial

fulfillment of this vision.

Scouts in the Indian Camp had seen Reno's column approaching, but it was decided

that nothing would come of that. Sitting Bull believed that the army was waiting

for reinforcements, and he had no expectations that an attack was imminent. Then

on the morning of the 25th, two Cheyenne Scouts came running into camp,

indicating that a large group of soldiers was approaching. Undoubtedly, this led

to the commotion that Custer misread as a panic retreat.

Of course, such a report would mean that the women and children had to be

hurried away, the great herds of horses brought in, and the warriors assembled

to meet the coming adversary. Even as the great chiefs were running to the

council lodge there came the report of gunfire from the south. This was Reno's

attack, which the Indians were not expecting.

It is reported that the unexpected

attack of Reno, and the report that "Long Hair" was dashing up the ravine was

too much for Sitting Bull. He is reported to have gathered his family and made

his escape to safety. Several miles from the battle, he realized that he

was missing one of his children. As he began to return for the missing child, he

was surprised to hear the battle waning, and everything becoming quiet. He

returned to camp in about 30 minutes, where he found his child. He also found

that the battle had been won in his absence.

Without him the Blackfeet and Uncapapas had pushed Reno back and penned him on

the bluffs. Without him the Ogalallas, Brulés, and Cheyennes had repulsed

Custer's daring assault, then rushed forth and completed a circle of death that

consumed Custer, and all the men with him.

Again, it was Crazy Horse who was

foremost in the fray, riding in and clubbing the bewildered soldiers with his

immense club of war.

On this day, Sitting Bull's vision was fully realized, but he was not there.

Some loyal followers claimed that he had directed the battle from the lodge. The

truth lay in the names given to Sitting Bull's twins- "The one that was Taken",

and "The one that was Left".

In the years after the conflict, many warriors would tell of their great

exploits in the great battle. Rain in the Face would even brag that he had

killed Custer with his own hand. In the midst of all the bravado and story

telling one man emerged as the man most respected by his comrades on that

glorious day. The man most respected by

the Indians on that day, for his bravery and leadership, was Crazy Horse. Crazy

Horse was killed not long after the battle as he tried to escape Crook's guard.

George Armstrong Custer

(1839-1876)

Flamboyant in life, George Armstrong Custer has remained one of the best-known

figures in American history and popular mythology long after his death at the

hands of Lakota and Cheyenne warriors at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Custer was born in New Rumley, Ohio, and spent much of his childhood with a

half-sister in Monroe, Michigan. Immediately after high school he enrolled in

West Point, where he utterly failed to distinguish himself in any positive way.

Several days after graduating last in his class, he failed in his duty as

officer of the guard to stop a fight between two cadets. He was court-martialed

and saved from punishment only by the huge need for officers with the outbreak

of the Civil War.

Custer did unexpectedly well in the Civil War. He fought in the First Battle of

Bull Run, and served with panache and distinction in the Virginia and Gettysburg

campaigns. Although his units suffered enormously high casualty rates -- even by

the standards of the bloody Civil War -- his fearless aggression in battle

earned him the respect of his commanding generals and increasingly put him in

the public eye. His cavalry units played a critical role in forcing the retreat

of Confederate General Robert E. Lee's forces; in gratitude, General Philip

Sheridan purchased and made a gift of the Appomatox surrender table to Custer

and his wife, Elizabeth Bacon Custer.

In July of 1866 Custer was appointed

lieutenant-colonel of the Seventh Cavalry. The next year he led the

cavalry in a muddled campaign against the Southern Cheyenne. In late 1867 Custer