Second Trial

Judge Allows Lesser Charge In Trial

of Subway Pusher

Print Single-Page Save Share

DiggFacebookNewsvinePermalinkBy JULIAN E. BARNES

Published: March 22, 2000

The judge presiding over the second

murder trial of a schizophrenic man who pushed a woman to her death in front of

a speeding subway train ruled yesterday that the jury could consider a lesser

charge, manslaughter.

The charge of second-degree manslaughter, which carries a sentence ranging from

probation to 5 to 15 years in prison, was not included in the first trial

of the defendant, Andrew Goldstein, which ended in November with a hung jury.

Mr. Goldstein, 30, has admitted pushing the woman, Kendra Webdale, 32, to her

death on Jan. 3, 1999, but maintains

that he was not responsible because of his illness.

The lesser charge could offer

jurors a compromise if they have difficulty reaching a unanimous decision to

either convict Mr. Goldstein of second-degree murder or find him not guilty by

reason of insanity.

Kevin Canfield, a defense lawyer, made the request yesterday in State Supreme

Court in Manhattan, with the jurors not present. Prosecutors objected, but Mr.

Canfield said that because Mr. Goldstein had claimed in his videotaped

confession that he had not intended to kill Ms. Webdale, jurors should be given

the option of convicting him of manslaughter, and the judge, Carol Berkman,

agreed.

Mr. Canfield rested his case yesterday without calling Mr. Goldstein to the

stand. Mr. Goldstein had told Justice Berkman on Monday that he wanted to

testify, but yesterday his lawyers persuaded him to change his mind, Mr.

Canfield said.

Before the trial began last month, Mr. Canfield had said he wanted Mr. Goldstein

to testify while he was off his antipsychotic medication, so that the jury could

see what his condition had been at the time of the attack. But a week before the

trial began, while he was off his medication, Mr. Goldstein struck a social

worker, and the judge ordered him to be offered his medication every day. Mr.

Goldstein has been on the drug since the trial began.

In his closing arguments, Mr. Canfield accused the lead prosecutor, William

Greenbaum, of trying to diminish Mr. Goldstein's illness and wrongly portraying

him as a faker.

''Mr. Greenbaum is trying to tell you, 'If he is not drooling, if he is not

walking along like Frankenstein, he is responsible,' '' Mr. Canfield said.

''Don't believe it.''

Although defense lawyers in the first trial made much of how the system had

failed Mr. Goldstein, Mr. Canfield avoided those arguments, instead focusing on

the depth of Mr. Goldstein's illness. After the first trial, some jurors said

they had been hesitant to acquit Mr. Goldstein for fear that he would simply be

returned to a mental health system that had continually turned him out on the

streets.

''I apologize to my client, but he is not the man he was,'' Mr. Canfield said.

''If it wasn't for this illness, would Andrew Goldstein kill anyone? No.''

During most of the closing arguments, Mr. Goldstein looked straight ahead or

down at the defense table. He seemed to pay attention only when prosecutors

played, once again, his confession. Prosecutors contend that Mr. Goldstein was

not psychotic on the day he strode behind Ms. Webdale and shoved her in front of

the train.

In his closing argument, Mr. Greenbaum again argued that Mr. Goldstein had used

his illness to shield himself from the consequences of his misdeeds. Mr.

Greenbaum walked jurors through a detailed accounting of other attacks by Mr.

Goldstein in which he had told the police that he needed treatment for his

mental illness.

''This defendant has demonstrated a history of insulating himself from his

actions,'' Mr. Greenbaum said. ''He had done it time and time again, taking

advantage of people of good will, saying, 'I'm psychotic, take me to the

hospital.' ''

Defense lawyers have argued that the very act of killing Ms. Webdale was insane,

because it lacked reason or justification. But Mr. Greenbaum said Mr. Goldstein

had killed Ms. Webdale to get back at her for ignoring him and to exact revenge

on another blond woman on the subway platform who had spoken to him

sarcastically.

Juror and Court System Assailed in Mistrial

Print Single-Page Save Share

DiggFacebookNewsvinePermalinkBy DAVID ROHDE

Published: November 7, 1999

Saying he was so angered by the outcome of the Andrew Goldstein trial that he

wanted to publicly apologize, the jury foreman has lashed out at a fellow juror

and at New York's court system.

''I'm just devastated,'' he said in an interview last week. ''This is a

travesty.''

The foreman, Karl

Bathmann,

was referring to the unexpected end of the trial on Tuesday, when a mistrial was

declared after the jury said it was hopelessly deadlocked at 10 votes to convict

Mr. Goldstein and 2 to acquit him by reason of insanity.

It was later revealed that one of the jurors who had opposed the conviction of

Mr. Goldstein, who was charged with murdering Kendra Webdale by pushing her in

front of a subway train, had recently been prosecuted by the Manhattan district

attorney's office. That juror, Octavio Ramos, was convicted of harassment and

resisting arrest three weeks before he became a juror, a fact that probably

would have disqualified him.

But neither the prosecutor nor the judge

had apparently asked Mr. Ramos whether he had been convicted of any crimes. Mr.

Goldstein is to be tried again next year.

Mr. Bathmann and other jurors said in interviews last week that they were

furious at Mr. Ramos, disappointed in the courts for allowing him to serve on

the trial and disenchanted by the experience.

Instead of soberly weighing the evidence, Mr. Bathmann said, the jury spent five

days furiously screaming at one another.

''It was just horrendous day after day,'' he said. ''It was screaming and

yelling and fighting.'' The foreman, a 61-year-old retired airline employee,

called the jury's failure to reach a verdict and the resulting need to retry Mr.

Goldstein ''a travesty.''

Jurors and legal experts said that the trial highlighted a variety of reforms

that are needed in the system. But in a reflection of how polarizing the issue

of the insanity defense remains, there was little unanimity on what kind of

changes to make.

Jewess clown judge

|

The most glaring error appears

to be the failure of the judge, Carol Berkman, or the prosecutor, William

Greenbaum, an assistant district attorney, to discover Mr. Ramos's

misdemeanor conviction.

Exactly what happened was still unclear Friday. Prosecutors and

court officials said they could not get a transcript of Mr. Ramos's

questioning because the court stenographer involved was busy with other

work.

|

Assuming that Mr. Ramos was not asked the question, defense lawyers said, the

mistake was caused partly by the increasingly short time that prosecutors and

defense lawyers are given to question prospective jurors. In the Goldstein

trial, Acting Justice Berkman of the State Supreme Court gave each side roughly

one minute for such questioning, said Jack Hoffinger, one of Mr. Goldstein's

lawyers. That amount of time, he said, has become the norm.

David Bookstaver, a spokesman for the court system, said the courts have

mandated no decrease in the amount of time lawyers are given to question jurors

in criminal cases.

Others argue that juries of lay people should not be asked to decide the complex

issue of insanity. H. Richard Uviller, a professor at Columbia University Law

School, favors having a judge decide a defendant's sanity. But Julia Vitullo-Martin,

director of the Citizens Jury Project, said the state's ''complex and

confusing'' insanity defense standard should first be simplified before the use

of a jury is scrapped.

The family of Ms. Webdale has said New York should adopt a type of verdict used

in a dozen states that allows defendants to be found ''guilty but mentally

ill.'' Under that verdict, a defendant receives mental health treatment but is

required to serve the full prison sentence.

But mental health advocates say that such a standard results in defendants

simply going to prison and receiving shoddy mental health care there. Legal

scholars argue that this verdict allows juries to avoid making difficult

decisions and keeps them from issuing the moral pronouncement that is one of the

main purposes of being judged by peers: whether or not defendants are

responsible for their actions and should be punished.

1999

The only thing the various sides could agree on was that Mr. Goldstein's trial

was far from satisfying. Philip H. Dolinsky, 34, a schizophrenic man who

followed the trial, said jurors' assumptions about Mr. Goldstein's family were

unfair and that the defendant was stigmatized because he is mentally ill.

''In most families with a mentally ill child, there is a disassociation with the

family,'' he said. ''I have the same problem.''

Patricia Webdale, the mother of the victim, said in a telephone interview from

her home outside Buffalo that Mr. Ramos, the more adamant of the two holdout

jurors, probably had empathy for Mr. Goldstein because he had just been a

criminal defendant himself. She said she

wanted to know why the mistake was made and was still struggling with the

trial's jarring conclusion.

''It's funny, now that I'm back home and away from it all, the sadness is

setting in,'' she said, referring to the lack of resolution in the case. ''I'm

just in shock. I feel like I did when Kendra died.''

Desciption

Witness Tearfully Describes Fatal Subway Shoving

Print Single-Page Save Share

DiggFacebookNewsvinePermalinkBy DAVID ROHDE

Published: October 9, 1999

A weeping 24-year-old woman recounted

yesterday how she shunned a bizarre-acting man in a Manhattan subway station in

January and then watched in horror as he abruptly hurled another young woman in

front of a speeding subway train.

Testifying between sobs at the murder trial of Andrew Goldstein, Dawn Lorenzino

described how she grew nervous when the odd young man stood next to her. She

snapped at him, ''What are you looking at?''

Minutes later, she said she watched as the man

pushed another woman, Kendra

Webdale,

off the platform with such force that she flew into the air out over the subway

tracks. It was an attack that was perfectly timed to coincide with the arrival

of a train, Ms. Lorenzino said. She said Ms. Webdale seemed to hover in

midair for an instant, with her arms and legs spread apart, ''exactly like a

skydiver.''

''She was flying through the air,'' Ms.

Lorenzino

said in a wrenching account that brought a juror and Ms.

Webdale's

family to tears. ''She didn't have a chance to scream. She had no idea what was

happening.''

The testimony of Ms. Lorenzino, who said she was standing six feet from Ms.

Webdale when she was pushed, came during the second day of Mr. Goldstein's trial

for second degree murder in State Supreme Court in Manhattan. Her description of

Mr. Goldstein's demeanor and actions could prove pivotal to jurors weighing

whether Mr. Goldstein, a schizophrenic who has pleaded not guilty by reason of

insanity, was sane at the time of the attack.

Her description of a calculated, timed

attack could help the prosecution's argument that Mr. Goldstein was sane at the

time. But her account of how strangely Mr. Goldstein was behaving could

bolster the defense's argument that he was not.

Harvey

Fishbein,

Mr. Goldstein's defense lawyer, argued that Mr. Goldstein had stopped

taking his antipsychotic medication and was legally insane at the time of the

attack. He said Ms. Webdale's death was the result of a shoddy state mental

health care system that shunted Mr. Goldstein, 30, in and out of institutions.

Prosecutors contend Mr. Goldstein is using his mental illness as a shield and

that Ms. Webdale's death was the culmination of anger he had toward women.

Assistant District Attorney William Greenbaum said in his opening statement on

Thursday that Mr. Goldstein pushed Ms. Webdale, 32, onto the tracks because he

was angry at Ms. Lorenzino for rebuffing him as they stood on the platform. He

said Mr. Goldstein was eyeing the two blond women before the attack.

In her testimony, Ms. Lorenzino described how a mundane 10-minute wait for a

subway train to her father's birthday party turned into an ordeal that

progressed from unease to fear to abject horror. She said she entered the subway

station of the N line at 23d Street in Manhattan at dusk on Jan. 3 just behind

Mr. Goldstein and immediately noticed that he was acting strangely.

''I saw a man walking in front of me walking oddly,'' Ms. Lorenzino said.

She said Mr. Goldstein would take a few ''baby steps'' on his ''tip toes'' and

then stumble. Mr. Goldstein then started walking normally, then paced furiously

back and forth on the southern end of the platform. He mumbled to himself and

eyed Ms. Lorenzino and Ms. Webdale, who was reading a magazine about six feet

away from Ms. Lorenzino, each time he passed them. Mr. Goldstein's pacing was so

intense that it prompted one man to cry out: '' 'Yo buddy, can you stop pacing?

You're making us nervous,' '' Ms. Lorenzino said.

As the wait for a train dragged on, Mr. Goldstein walked up to Ms. Lorenzino and

stood beside her, she said. ''I felt very uncomfortable that he was standing

next to me,'' Ms. Lorenzino said. ''I said, 'What are you looking at?' Then he

backed off as if he was frustrated. ''

Mr. Goldstein paced for a few more minutes, Ms. Lorenzino said, looked down the

track as if checking for a train and then walked down the platform to Ms.

Webdale. ''Do you have the time?'' he asked her. Ms. Webdale glanced at her

watch and answered, ''a little after five,'' Ms. Lorenzino said. Mr. Goldstein

then positioned himself against the wall behind Ms. Webdale, who returned to her

magazine, Ms. Lorenzino said.

Published: October 9, 1999

When the train sped into the station,

she said, Mr. Goldstein ''darted'' off the wall and violently pushed Ms.

Webdale.

Ms. Lorenzino

said she was struck by how well-planned the push seemed. It gave Ms.

Webdale

no time to escape.

''It was perfect,'' she said, referring to the timing. Ms.

Webdale's

body never hit the rails, she said, ''she just flew right under the train.''

Police Officer Raymond McLoughlin, who also testified yesterday, said he arrived

at the station to find people shouting ''He's right here! He's right here!'' He

found Mr. Goldstein, who made no effort to escape, sitting on the platform with

his legs crossed, surrounded by 20 enraged people who were berating him, he

said.

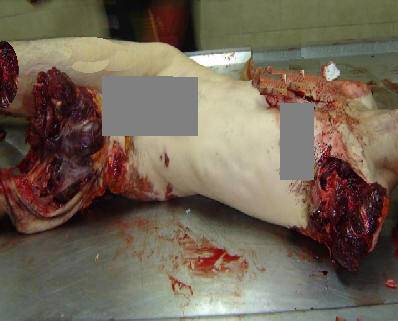

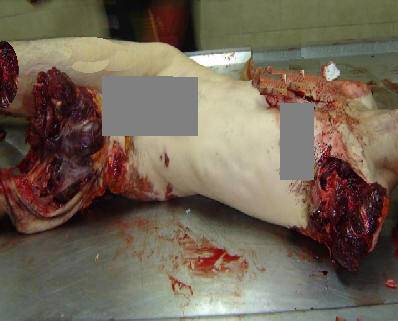

body parts

|

Another police officer cried

out ''I see a leg!'' Officer McLoughlin said. Then, the officer

testified, Mr. Goldstein looked at him, and at the train, and quietly

said, ''I don't know the woman. I pushed her.''

|

| |

|

< Previous Page1 2

Andrew Goldstein, who first faced charges in January 1999.

E-MailPrint Reprints Save

By ANEMONA HARTOCOLLIS

Published: October 11, 2006

A schizophrenic man pleaded guilty to manslaughter yesterday, admitting

for the first time that he knew what he was doing when he pushed a promising

young writer to her death in front of a subway train almost eight years ago.

Kendra Webdale

The man, Andrew Goldstein, acknowledged that he knew it was wrong to shove the

woman, Kendra Webdale, 32, into the path of an N train at the 23rd Street

station in January 1999.

The death of Ms. Webdale, a journalist and photographer who had moved to the

city from Buffalo, unnerved New Yorkers who had come to think of their city as

the safest it had been in years. The public outcry over her death led to a state

law, known as Kendra’s Law, that gives families the right to demand

court-ordered outpatient psychiatric treatment for their relatives.

Until his plea yesterday in State

Supreme Court in Manhattan, Mr. Goldstein had claimed that he had pushed Ms.

Webdale

during a psychotic episode and therefore was not responsible for his actions.

“She was leaning against a pole with her back to me near the edge of the

platform by the tracks,” Mr. Goldstein said in a written statement submitted

yesterday to Justice Carol Berkman. “I looked to see if the train was coming

down the tracks. I saw that the subway train was coming into the station. When

the train was almost in front of us, I placed my hands on the back of her

shoulders and pushed her. My actions caused her to fall onto the tracks.”

Mr. Goldstein, 37, pleaded guilty in a

deal negotiated by prosecutors with the consent of Ms. Webdale’s family.

He was promised 23 years in prison with five years of postrelease supervision —

including psychiatric oversight — at his sentencing, set for next Tuesday.

The plea came as he was about to be

tried for the third time. Mr. Goldstein was convicted of second-degree

murder in his second trial, in March 2000, after the first ended in a hung jury.

He was serving 25 years to life, the maximum, when his conviction was overturned

last December by an appeals court that found he had been denied a fair trial.

Couldn't handle another trial

Ms. Webdale’s

sister Kim Emerson said yesterday that her family had agreed to the plea deal

because they could not bear the trauma of going through another trial with an

uncertain outcome. She said it was both painful and a relief to hear Mr.

Goldstein admit his guilt.

“I miss my sister,” Ms. Emerson said after the hearing yesterday, during which

she sat silently with the other spectators. “It brings back what happened on the

platform, and to hear him say that he did push her and it was intentional was

really hard to hear.” At the same time, she added, “to hear him express it was

difficult, but satisfying.”

She said the agreement that Mr. Goldstein would be monitored by psychiatrists

after his release was important to her family. “The certainty that he won’t do

this to anybody else has been our goal all along,” she said.

Prosecutors said Ms.

Webdale’s

family planned to make a statement to the judge before Mr. Goldstein’s

sentencing. Ms. Webdale was the third of six children, and 20 months

younger than Ms. Emerson.

Mr. Goldstein’s schizophrenia was diagnosed 10 years before Ms. Webdale was

killed. A graduate of the Bronx High School of Science, he was living in Howard

Beach, Queens, at the time of his arrest.

His lawyers blamed his failure to take antipsychotic medication for Ms.

Webdale’s death, and said the state mental health system had repeatedly sent him

back to the streets despite a history of violent behavior and his own requests

for treatment. The prosecution contended that he had a history of using his

sickness as an excuse for bad behavior.

In Mr. Goldstein’s first trial, the jury deadlocked over whether he should be

found not guilty by reason of insanity. The second jury found that he had known

what he was doing, and convicted him of second-degree murder.

But the Court of Appeals, the state’s

highest court, overturned that conviction, finding that Mr. Goldstein’s

constitutional right to confront witnesses against him had been violated.

The appeals court said Justice Berkman had erred in allowing a psychiatrist to

testify about what other people had said about Mr. Goldstein’s mental condition

when those people were not available for cross-examination.

“What I’ve learned from this whole experience is that there’s no certainties

with the justice system,” Ms. Emerson said. “It would be very difficult

emotionally to sit through another trial and possibly future appeals. I know my

mother is definitely ready to have this be finished.”

As part of his plea, Mr. Goldstein had to answer questions meant to determine

whether he was pleading guilty of his own free will, and whether he understood

the charge.

“On Jan. 3, 1999, did you push a woman

you came to know as Kendra

Webdale to her death?” Justice

Berkman

asked him yesterday.

Mr. Goldstein answered, “As much as I can understand, I did that.”

Justice Berkman said she was not sure what he meant, and Mr. Goldstein’s lawyers

whispered to him at the defense table. He then changed his answer to a simple

“yes.”

The judge asked whether he had intended to cause serious injury.

“Yes,” he said. “But not necessarily death.” After another conference with his

lawyers, he added, “Yes, yes.”

In the nearly eight years since Ms. Webdale was thrown to her death, her mother,

Patricia Webdale, has become an advocate for the mentally ill. Ms. Emerson said

yesterday that her family had received some consolation from the knowledge that

Kendra’s Law had helped other people receive treatment. “It’s a wonderful

legacy,” Ms. Emerson said.