What were the Nuremberg Trials?

They were a series of 13 trials of accused World War II German war criminals

held from 1945 to 1949 in Nuremberg, Germany. The first trial, the

International Military Tribunal (IMT), was prosecuted by the four Allied

powers against the top leadership of the Nazi regime in 1945-1946. The other

twelve trials were prosecuted by the United States in the Nuremberg Military

Tribunals (NMT) from 1946 to 1949, against a variety of governmental,

military, industrial, and professional leaders.

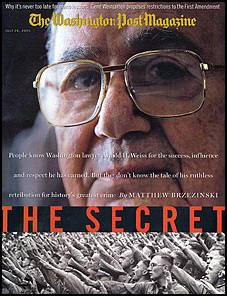

washingtonpost.com

Correction to

This Article

Arnold H. Weiss, a Washington lawyer and former Nazi-hunter, is referred

to as Albert Weiss in a headline in today's Magazine, which was printed in

advance. The headline on this online version of the article has been

corrected.

Giving Hitler Hell

By Matthew Brzezinski

Sunday, July 24, 2005; W08

|

When Nazi decrees destroyed Arnold Weiss's family, leaving him

abandoned, it would have been hard to imagine this powerless child one

day returning to Germany to mete out a rough justice of his own.

This is the story of a man who has stared evil in the eye and held

the fates of mass murderers in his hands. It begins at a company picnic,

where children are cavorting as their parents dine on healthful salads

and low-carb entrees. This is appropriate, in a roundabout way, because

alongside the theme of hard, brutal justice, this story also concerns

the American dream.

|

The setting is the Tarara Vineyard just outside Leesburg, and the date is

summer 2002. The suburban winery has been transformed into a mini-amusement

park for the occasion. Portable generators hum, powering all sorts of play

stations, slides and rides. Overhead, a hot-air balloon rises and falls on its

tether like a giant red yo-yo. Kids run in every direction, trailed by harried

parents, the occasional nanny and a professional photographer hired to

memorialize the corporate outing. A group of executives huddles near the

outdoor buffet. They wear baseball caps em-blazoned with the logo of their

employer, EMP, or Emerging Markets Partnerships, one of Washington's largest

international investment firms. Some sip merlot, but in the presence of their

bosses most of the assembled MBAs have opted for the safer soft-drink

selections.

|

Arnold H. Weiss stands

at the center of this pleasant bustle. He is a small, dapper man,

slightly stooped, and he speaks so softly that those at the back of the

pack must crane their necks to see and hear him. But everyone is

listening intently, and not only because he is one of the firm's

founders, and, at 78, its eldest statesmen. Weiss's tone is detached and

measured, almost clinical, as if he were outlining exit strategies for

an Indonesian telecom deal or plotting the purchase of a Brazilian

railroad. But he is not talking shop. He is relating his experiences

from the Holocaust.

Several of the senior partners have heard parts of the story before,

and they drift in and out of the circle as

Weiss recounts his years in an

Orthodox Jewish orphanage near Nuremberg, where the Nazis first

wrote their deadly race laws. A murmur of surprise rises from the

younger employees when they discover that one of their board members was

Weiss's classmate in Germany: Henry Kissinger. But silence descends

again, as Weiss recalls running the gantlet through Hitler Youth gangs

on his way to school every day, and the foot chases, the beatings in

alleys and the scar he bears to this day from being strung up on a

lamppost by teenage Nazi wannabes.

|

| |

|

| Every so often

one of the executives in Weiss's audience is called away to deal with

an unruly offspring or to soothe a toddler meltdown, and when that

person returns, the narrative has moved forward. The Second World War

has begun, and everyone in Weiss's orphanage has been sent to the

extermination camp in Auschwitz. Young Arnie, however, is safely in

the United States, having made it out of Germany in 1938 in one of the

so-called Kindertransports that rescued thousands of Jewish children

from the gas chamber. He is 13 when he arrives in this country, with

only a cardboard suitcase and $5 to his name. He does not speak a word

of English or know a single soul.

|

|

|

|

|

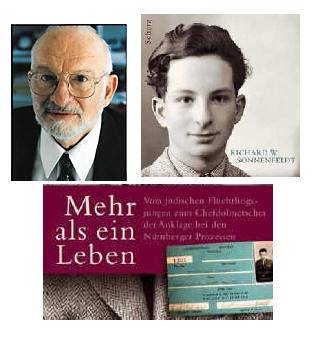

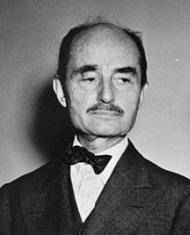

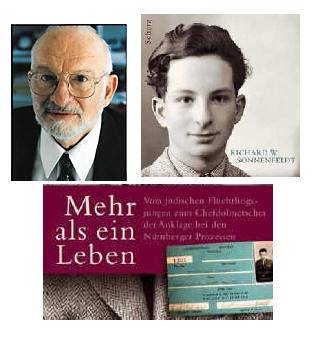

Weiss as a 18 yr old in

Milwaukee

Now it is 1945, and the

21-year-old Weiss is back in Germany as a U.S. military intelligence

officer trained by the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor of

the CIA. Hitler's armies are in retreat, and Weiss, a newly minted

American, is sent behind enemy lines into Dachau, the German

concentration camp, on a daring mission.

|

By this juncture in the tale, the executives huddled around Weiss are

riveted.But Weiss seems anxious to wrap up his reminiscing just as the war

ends and the real work of his Army intelligence unit begins: tracking down

fugitive Nazis. He has grown visibly tired by the retelling, as if suddenly

burdened by some great weight.

His employees can't conceal their disappointment. They clamor for more

details. Weiss deflects the queries, summoning his half-century of experience

as a Washington lawyer to carefully craft each response. The questions,

however, keep coming.

|

Admits

killing German prisoners

"You must understand," he

acknowledges after some time, "that I'm not ready to talk about what

happened."

But why? someone asks.

For a moment Weiss stares

silently through his large, gold-rimmed glasses. "Because," he finally

says, "there is no statute of limitations on murder."

|

Since Arnold Weiss's signature adorns my wife's paycheck, I thought it

prudent not to push too hard during that 2002 picnic. My curiosity, however,

had been aroused, and I made it clear that if he ever wanted to tell the full

story of what did happen in the weeks and months after Nazi Germany's

capitulation, I would be an obliging listener.

Three years passed, and I did not hear from Weiss. I'd run into him at the

occasional Christmas party or EMP function requiring black tie and spousal

attendance, but he never brought up the subject. Then, a few months ago, Weiss

left me a message: If I was still interested in hearing his story, he was at

last prepared to tell it.

Weiss is almost 81 now, officially -- and grudgingly -- retired, though

you'd never know it, since he still gets up each morning, dons a tailored suit

and drives his big Mercedes to EMP's offices on Pennsylvania Avenue. He's

married and has two grown sons. He missed three months of work last year

recovering from a triple bypass and heart valve surgery, and while he

certainly looks fit and healthy, perhaps an impending sense of mortality has

made the time seem right.

|

The buzz around the office is

that Weiss will outlive the interns. That he has outlasted most of his

WWII buddies is not, however, a source of comfort to him. Virtually

every time he logs on to the Web site of the Army Counter Intelligence

Corps veterans association -- Weiss is member number 3326 -- there's

news of yet another colleague's passing. Soon, Weiss worries, all the

eyewitnesses will be gone, and only the written record will remain. And

that record is incomplete. "They took their secrets to their grave,"

says Weiss of his deceased fellow officers.

|

Ironically, an almost identical consideration recently prompted Adolf

Hitler's devoted nurse, Erna Flegel, to break her 60-year silence on Hitler's

deteriorating mental and physical health in his final days. "I don't want to

take my secret with me into death," the 93-year-old Flegel told a German

newspaper in May. There are still many missing pieces of the WWII puzzle, and

every time one is found history gets rewritten a bit. Sometimes, as in the

case of the unrepentant Flegel, whose existence became known only a few years

ago when the CIA declassified old OSS interrogation transcripts, the added

testimony merely warrants a footnote. But on other occasions, material

surfaces that requires entire chapters of the official record to be scrapped.

It was only after the collapse of communism, for instance, that the Kremlin

grudgingly admitted that the Soviet secret police, not the German SS, murdered

thousands of Polish POWs during WWII. In 2000, it was Poland's turn to

reexamine its war record, and the larger issue of anti-semitism, when an

American scholar uncovered evidence that the

massacre of the entire Jewish

population of a village called

Jedwabne was the work of

Polish compatriots and not the Nazis, as had been the official version.

History has a habit of sweeping the inconvenient under the carpet. Despite

the passage of more than half a century (not to mention the passage of U.S.

legislation in the late 1990s ordering WWII records unsealed) there are still

countless documents from the era that the CIA has deemed either too sensitive

or embarrassing to declassify. Like those partially opened files, parts of

Weiss's account have also emerged slowly over the years, and the snippets of

the past they offer contain eerie parallels to some of the things happening in

the world today. But he, too, has held back crucial portions of the narrative.

Now, for the first time, he's willing to tell the whole story, from its

improbable beginning to the strange new relevancy of its long-buried end.

Munich in autumn of 1945 was

a devastated and demoralized city. With every passing week, the

arrest lists sent from American

intelligence headquarters in Frankfurt only seemed to grow longer. The

teletype machine next to Weiss's desk spat out names almost round-the-clock:

rocket scientists, nuclear engineers, chemists and physicists; party clerks,

accountants and financiers; valets, chauffeurs and cooks. Anyone closely

associated with the fallen regime had to be hauled in and detained. And in a

town like Munich, whose smoky beer halls had hosted the earliest Nazi rallies,

that meant a great many people.

Life In Nuremberg

|

Jews

requisition mansions

Weiss and two dozen other

Army Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) officers worked out of the

requisitioned home of Munich's gauleiter, or local Nazi Party boss, who

had seized the villa from a wealthy Jewish industrialist. The mansion

had somehow survived Allied air raids and was in a quiet, upscale

neighborhood that was also relatively undamaged. But perhaps its chief

recommendation was a deep, dry basement that had been converted into

holding cells.

|

From Gauleiter Haus, Weiss's beat -- Region IV of the American Occupied

Zone -- stretched south through the lakelands and forests of Bavaria to the

Alpine passes and mountainous redoubts along the Austrian border. Bavaria was

the cradle of the Nazi movement, the birthplace and home of many of its

leading figures. And because of its mountainous terrain and the fanaticism of

some of its inhabitants, it was the one area in the American Sector that posed

the greatest risk of insurgency, the German equivalent of the Sunni Triangle.

Throughout Germany, the Allies were anxious to restore basic services and

get local governments up and running again, and one of Weiss's

responsibilities was to vet potential officials for past Nazi Party

membership. It was an important and time-consuming duty, but he still kept a

special eye out for high-value targets who had evaded capture. Many of

Hitler's henchmen, particularly from the dreaded SS, were still at large,

along with mountains of gold bullion, and if there was to be an uprising, they

would surely lead and finance it. Already, sporadic attacks by a group of

insurgents ominously known as the Werewolves had prompted standing orders for

GIs to execute insurgents by firing squad. This wreaked havoc on the morale of

U.S. servicemen, especially since many of the troublemakers were 16- and

17-year-old former Hitler Youth members.

More worrisome, though, were the persistent rumors that Hitler was still

alive. "We were certain that he had committed suicide at his bunker," Weiss

recalls. "But since Berlin was part of the Russian zone, and no witness and no

body had been produced by the Soviets, many Germans refused to believe the

Fuhrer was gone."

|

|

The Jewish CIC sought revenge

The rumors that Hitler had survived were becoming a serious issue,

not to mention a potential rallying cry for those Germans who refused to

accept defeat. There was talk that Hitler was hiding in a cave in

northern Italy, that he was disguised as a shepherd in the Swiss Alps,

that he was working as a croupier in Evian, France. One report in August

1945 had him living in Innsbruck under the alias Gerhardt Weithaupt.

(Thirty CIC agents chased down that lead, according to the 1996 book The

Death of Hitler, by Ada Petrova and Peter Watson.) In another account,

Hitler was with a fleet of U-boats off the coast of Spain.

|

The Russians, who knew full well where the late Fuhrer was since they had

his charred remains in a secret laboratory in Moscow, further stirred the pot.

Izvestia, the official Communist daily, ran a front page story claiming that

he and Eva Braun had installed themselves in bourgeois splendor in a castle

(complete with moat) in Westphalia, in the British Zone.

Hitler sightings soon spanned the globe, from Sweden and Ireland all the

way to Argentina, where Hitler, having undergone plastic surgery, was said to

be developing long-range robot bombs in an underground hideout. Even

Washington caught the paranoia bug, sending an urgent classified cable to its

embassy in Buenos Aires to run down the lead: "Source indicates that there is

a western entrance to the underground hideout, which consists of a stone wall

operated by photo-electric cells, activated by code signals from ordinary

flashlights." The matter was apparently taken seriously enough, according to a

1989 book on the CIC, America's Secret Army, by Ian Sayer and Douglas Botting,

that FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover became involved in the investigation. By

October 1945, speculation over Hitler's whereabouts had reached such a fever

pitch that a decision "at the highest level," says Weiss, was made to put the

mystery to rest once and for all. The British -- who were particularly

incensed at the Soviet suggestion that Hitler was living untrammeled under

their noses -- were charged with finding definitive proof that Hitler was

dead. Messages now clattered off the CIC teletype machines to give the highest

priority to the search for eyewitnesses who may have been in the bunker with

Hitler during his last days.

"The highest-ranking Nazi who was still on the loose was Bormann," says

Weiss. Martin Bormann, the Brown Eminence, had been the Nazi Party secretary

and Hitler's gatekeeper. He had controlled access to the Fuhrer. If anyone

knew what had happened to Hitler, it was Bormann. "I remembered vaguely that

his adjutant was from Munich."

Weiss tortures mother and sister?

|

Weiss scoured the records, and

discovered that Bormann's

right-hand man, SS Standartenfuhrer Wilhelm Zander, indeed hailed

from Munich, and was still unaccounted for. Zander not only might know

where his boss was hiding, there was a good chance that he had been in his

bunker just before the Red Army stormed it. Weiss picked up the Munich

phone book. Sure enough, there were several Zanders listed. "I rounded

up his mother and sister," Weiss recalls. He was struck by how ordinary

they seemed. That was something Weiss would grow accustomed to: how

monsters could come from such seemingly normal families.

|

| Though the mother and

sister were defensive and insisted that Zander had done nothing wrong,

eventually one of them let slip that he had a much younger girlfriend in

Munich. She was a striking

21-year-old brunette who still lived with her parents. Weiss had her

arrested. Though he himself was barely old enough to legally buy

beer by today's standards, Weiss could back then cordon off entire city

blocks and incarcerate everyone for any period of time. Warrants were not

needed, and there was no judicial oversight. "We had absolute power," he

says, with a small smile. "The Germans were already calling us the

American Gestapo." Weiss sent the girlfriend not to

CIC headquarters at the posh

Gauleiter Haus, but to a larger jail filled with common criminals

on the outskirts of Munich. There, he let her sit alone in a cell for two

days to contemplate her fate. "I wanted her frightened, to give her time

to think" of all the terrible things that could happen to her. It was a

standard interrogation technique with subjects who were considered weak.

Breaking hard cases required a completely different approach, and Weiss,

since he was one of the few American officers who spoke German, was

rapidly gaining experience as a skilled interrogator.

|

When he had deemed that she had stewed long enough, Weiss had the woman

brought to a barren interrogation room. He made her stand, another small but

apparently effective psychological tactic. "She was ready to talk," he

recalls. "She immediately admitted to being Zander's lover." Weiss asked when

she had last seen him. He expected her to say that it had been years, but

instead she said six weeks earlier. "My teeth just about dropped," Weiss

recalls. That meant the trail might still be hot. The woman had another

surprise for Weiss. Zander had foolishly told her the alias he was using and

where he was hiding. Weiss immediately sent a coded communique to CIC

headquarters in Frankfurt. U.S. intelligence notified British Intelligence,

which dispatched its lead investigator to join Weiss in the chase.

Maj. Hugh Trevor-Roper made an unlikely secret agent. Tall, gaunt and

nearsighted, he seemed more like a distracted academic, which in fact he was

in civilian life, a history professor at Oxford. Weiss briefed Trevor-Roper.

Zander was using the name Paustin and was posing as a farmhand for someone

named Irmgard Unterholzener in a village not too far from Munich called

Tegernsee. The pair made hasty arrangements to raid the place, but by the time

they arrived, Zander had bolted. For the next three weeks, Weiss chased down

blind leads without luck. Then, just before Christmas, Weiss got a call from

the CIC field office in Munsingen, Germany. A Paustin had registered for a

residence permit -- the Germans, apparently even when on the lam, were very

punctilious about recordkeeping -- with the local police in a small German

village near the Czech border called Vilshofen. Weiss got on the horn to

Trevor-Roper. "We found him," Weiss said excitedly. It took 24 long hours for

Trevor-Roper to get to Munich, during which Weiss paced impatiently.

When he finally arrived, the pair shouldered their weapons -- Weiss had a

holstered .38; Trevor-Roper opted for the larger Colt .45 -- and set out in an

open jeep for the chilly 90-minute drive to Vilshofen.

Hollywood, in Weiss's own words, could not have cast a more unlikely pair

of Nazi hunters. In photos, Trevor-Roper, in an ill-fitting uniform and

Coke-bottle glasses, towers thinly over Weiss, who though he weighed a scant

120 pounds when he enlisted, had rounded out his diminutive frame, thanks to

the Gauleiter

Haus'

well-provisioned mess table. But looks can be deceiving. The aristocratic

Oxford don (Trevor-Roper, who became one of the most preeminent WWII

historians, died Lord Dacre) and the brash Jewish-American refugee made a

formidable team.

At the Munsingen field office, they called for backup -- several MPs and a

junior CIC officer. Weiss is fuzzy on the latter's full name; a military

intelligence document of the period lists him only as

Special Agent

Rosener.

Weiss, Rosener and Trevor-Roper found the farmhouse shortly before 4 a.m.

It was an old stone building, prosperous and well kept, and all was quiet

despite the impending holiday. (At this stage, there seems to be some

discrepancy as to the chronology of events. Petrova and Watson list the raid

as occurring on Boxing Day, or December 26. Sayer and Botting have the date as

December 28. But Weiss, whose key role is noted in both books, still has a

memo he wrote at the time on CIC letterhead that puts the raid as having taken

place on Christmas Eve.) As the MPs broke down the door, a shot rang out from

the house. Weiss's first instinct after diving for cover was to disarm

Trevor-Roper. "He was pretty much legally blind, and I was more afraid of

getting shot by him than Zander," Weiss recalls. The MPs found the startled

Zander naked in bed with a woman (not his girlfriend) and quickly overpowered

him. Weiss grabbed Zander's Italian Beretta -- a memento he has kept to this

day.

The family who owned the house had come running downstairs, shocked at all

the commotion. There followed a good deal of yelling, not the least from

Zander, who was demanding to know who his captors were and what they wanted.

"We're Americans, and we've come to arrest you," said Weiss.

"Why?" Zander demanded.

"What's your name?"

"Paustin."

"Do you have ID?"

Zander produced an identity card: It listed him as in his late thirties, a

shade under 6 feet, and of medium build, which was all accurate. The photo too

showed a good likeness; dark hair and cool, light eyes forming an arrogant

gaze that had apparently made Zander/Paustin a ladies man.

"This is a fake," said Weiss. "You're coming with us."

The whole way back to Munich, as Weiss drove and Rosener guarded the

handcuffed prisoner, Zander maintained his innocence. "He kept screaming,

'What do you want from me?'" Weiss recalls. "And we kept saying, 'We'll tell

you when we get there.'"

When they arrived at Gauleiter Haus, they began the interrogation

immediately. "We wanted to go after him while the shock of the arrest was

still fresh." Trevor-Roper, as the senior officer, led the questioning, and

Weiss acted mostly as interpreter. For 10 hours they grilled Zander, who

initially continued to insist that his was a case of mistaken identity.

"We confronted him with all the facts of his life," Weiss recalls. The aim

was to show Zander that Allied intelligence already knew everything about him,

that there was no point in continuing the charade. Zander's answers started

growing contradictory. Weiss turned up the heat.

"We have your mother and sister," he said. This wasn't true. Weiss had

arrested only the girlfriend. But Zander didn't know that.

Finally, and with great formality, he said: "You are correct. I am SS

Standartenfuhrer Wilhelm Zander."

It wasn't particularly dramatic, but they had broken him. The real

questioning could now begin. When had he last seen Nazi leaders Goebbels?

Goering? Himmler? Who was in the bunker with the Fuhrer during his last hours?

What were the circumstances of Zander's last meeting with Bormann? How did he

get out of the Fuhrer's bunker? What route did he take? Trevor-Roper was

particularly interested in the names of lesser officials present during

Hitler's last 48 hours, support staff such as Erna Flegel, cooks, drivers,

guards and so on.

Once Zander had given up the ghost of Paustin, he talked nonstop for six

hours. Almost as an afterthought, Weiss asked why he had left the bunker.

"I was sent on an important mission as a courier," said Zander,

matter-of-factly. "I suppose you want the documents."

Absolutely, said Weiss, even though he had no idea what Zander was taking

about. "Where are they?"

That same day Zander led Weiss and Trevor-Roper back to Tegernsee, where he

had originally lain low. There was a dry well at the back of the Unterholzener

property, and he pointed down it. Weiss retrieved a fake-leather suitcase from

the bottom. At first glance it contained only Zander's discarded SS uniform.

But upon closer inspection, a hidden compartment was found. In it was a plain

manila envelope.

Weiss tore it open. "Oh my God," he cried, involuntarily switching to his

native German. He was staring at Hitler's "Last Will and Political Testament."

"Let me show you something," says Weiss, breaking off his narrative. It

takes me a second to make the leap from 1945 to the pres-ent, to readjust to

the office surroundings. I take in the plush ex-ecutive decor, the crystal

tombstones that investment bankers use to commemorate big deals, the framed

notice from the June 6, 1994, edition of the Wall Street Journal:

$1,086,460,000, it reads in bold banner-headline print, the amount of money

raised for the first of six funds EMP manages. A scale model of a Boeing 757

flying the corporate colors of an Asian airline (one of the firm's

investments) sits on the window sill, competing for airspace with the real

planes that cruise over the Potomac on final approach to Reagan National

Airport.

"Here, I brought it with me." Weiss fishes through his briefcase, which is

definitely not fake leather. Everyone dresses well at EMP's posh Pennsylvania

Avenue headquarters, but only the chairman -- a former prime minister of

Pakistan and World Bank senior vice president -- is nattier than Weiss.

"There," says Weiss, handing me an old sheaf of papers.

They are 1946 photostats. What is startling is the simplicity of the

documents. With all the pageantry that surrounded the Third Reich, these

humble pages don't even contain an official seal. Printed on plain white

typing paper of the sort found lying around any office, they have an almost

suspect humility about them. But they are real, authenticated by the FBI in

early 1946, according to America's Secret Army.

Mein privates Testament, reads the underlined heading of the first page. It

is dated April 29, 1945, 4 a.m., and at the back are five signatures. The

first is small and tightly wound, like a compressed thunderbolt: Adolf Hitler.

The others are more expansive and boldly ambitious: witnesses Martin Bormann

and Joseph Goebbels, the propaganda minister who killed himself and his family

in the room next to Hitler in the bunker.

The same signatures grace a second, considerably longer document titled

Mein politsches Testament, in which Hitler rails against his generals, expels

Himmler and Goering from the Nazi Party, and appoints Grand Adm. Karl Doenitz

as his successor and names the entire 17-member Cabinet. A third document had

been in the package found by Weiss that Zander was to have delivered to

Doenitz -- the death-bed marriage certificate between Hitler and his longtime

mistress, Eva Braun. But Weiss did not get a copy of it. (Weiss received a

photostat of Hitler's wills along with a congratulatory memo dated January 7,

1946, from an American brigadier general whose signature is illegible. The

originals are stored in the National Archives.) "The wills were to be used to

re-honor Hitler, when at some future date the Germans would rise again," Weiss

wrote in his own sure hand in a 1946 memo that ends in a triumphant, "Case

closed." (Weiss had reason to sound exultant: For finding definitive proof

that Hitler was dead -- in his will, Hitler explains that he prefers ending

his own life to being paraded around like a zoo exhibit -- he was awarded the

Army Commendation Medal, a citation from the commanding general of the

Intelligence Services and a recommendation for the Bronze Star.)

As to why Zander failed to deliver the documents to Doenitz, Weiss's memo,

now yellowed with age, hints that such information was above his pay grade.

Trevor-Roper, however, had access to further debriefings with the wayward SS

courier. "A half-educated, stupid, but honest man," he wrote in his final

report, published in 1947, "Zander only wished by a silent death to end a

wasted life and expiate the illusions which it was too late to shed."

Apparently, the loyal SS man had begged for permission not to carry out his

last mission. An idealist, he wished to die alongside his Fuhrer. But,

according to Trevor-Roper, Hitler refused his request and ordered him to carry

the succession documents. Once he thought Hitler was gone, Zander no longer

believed that Nazi Germany had any future and simply ditched the documents

instead. Weiss never found Bormann, whose skeleton was discovered in Berlin in

1972, prompting speculation that he had killed himself not long after leaving

Hitler's bunker.

Weiss still marvels at Hitler's mix of naiveté and arrogance for thinking

that the Third Reich could survive defeat or that his orders would be carried

out after death. "Can you imagine?" he says. "Hitler was still trying to run

Germany from the grave. Talk about chutzpah!" But more mundane matters also

preoccupied Hitler's last thoughts: He wanted his paintings donated to a

picture gallery in his home town of Linz and some personal mementos

distributed to his secretaries, particularly Frau Winter. "As executor, I

appoint my most faithful Party comrade, Martin Bormann," Hitler wrote. "He is

given full legal authority to hand over to my relatives . . . especially to my

wife's mother . . . everything which is . . . necessary to maintain a

petty-bourgeois standard of living."

Hitler's final written words, however, commanded Germany's future leaders

to "mercilessly resist the universal poisoner of all nations, international

Jewry." It is, thus, one of history's ironies that the first person to read

those words was a young German American Jew who had survived the Holocaust as

a victim of Nazi persecution and was now acting as an instrument of justice.

Weiss was born Hans Arnold Wangersheim to a middle-class family of

assimilated Jews that had lived peacefully in German Franconia for nearly four

centuries. Weiss's father, Stefan, covered the sports beat for the Nuremburg

Acht-Uhr Abendblatt, and his flashy, opinionated columns on the rising or

falling fortunes of the local soccer clubs lent him an aura of minor celebrity

enjoyed by the contemporary likes of a Tony Kornheiser. Sportswriters in those

days didn't have production deals with ESPN, and the Wangersheims lived

modestly in a working-class neighborhood where the nascent forces of fascism

and communism competed fiercely, and often violently, for the residents'

affections.

Weiss's earliest memories of his father are of a muscular man in a crisp,

white gymnastics uniform, swinging gracefully from the parallel bars. "He cut

a dashing figure, or so it seemed to someone who was very young."

Weiss was 6 when his parents divorced in 1930.

His father apparently preferred the sweaty company of fellow sports lovers,

and long, languid evenings in beer halls, to ministering to his three

children. There might have been another woman in the picture, but the subject

was too painful, and Weiss never raised it with his mother. By all accounts,

the divorce proceedings were messy and bitter. Weiss's mother, Thekla

Rosenberg, an avid athlete and tennis player herself, got custody of young

Arnie and his two sisters, Beate and Evelyn, but no financial support from

Stefan, who walked away from all parental responsibility.

At the time, the Great Depression raged on both sides of the Atlantic. In

Weimar Germany, the added burden of war reparations demanded by the Treaty of

Versailles at the end of WWI made the situation particularly dire. Weiss's

mother had a difficult decision to make. On her bookkeeper's salary, she could

not afford to raise three children. "There was just not enough money to feed

all of us," Weiss recalls. "The girls needed to be more protected, so I was

the candidate to be placed in an orphanage."

The Orthodox Jewish orphanage to which Weiss was sent in 1930 (or 1931 --

he no longer remembers) was in a suburb of Nuremberg known as Furth. The

routine was harsh: up before dawn for morning prayers at the synagogue next

door, then off to school and three hours of Hebrew lessons, followed by two

more hours of Talmudic studies before evening prayers. The food was lousy;

privacy was nonexistent; and between the hazing from the older kids and the

harsh discipline meted out by orphanage administrators, beatings were a

regular feature of life.

Weiss described the details in an oral testimony he gave in 1996 to the U.S

Holocaust Memorial Museum. "It was pretty grim," he said in the taped

testimony, "even before the Nazis came to power."

Asked by the curator if he felt a sense of abandonment, Weiss responded,

"Yes," after a long pause. "I would say that's a fair comment."

The separation from his 2-year-old sister, Evelyn, was the hardest to bear.

"I simply adored her. She was like a toy." Weiss still got to see his mother

and sisters for a few hours every few months, but it wasn't the same. They

inevitably grew apart. But the orphanage was within walking distance of his

maternal grandmother's apartment, which afforded him at least one decent meal

a week and generous helpings of affection.

Still, he says, orphanage life wasn't all bad. You always had someone to

play with, so you were never lonely. Those hidings thickened the skin, and you

learned quickly to fend for yourself. "Community living, once you got used to

it, had all kinds of pluses, which came in handy at later stages in life."

Weiss credits his upbringing in the orphanage for his ease in institutional

settings, whether the military, in which he enlisted in 1942 as a gunner on

B-17 bombers before being recruited into intelligence, or the Treasury

Department, which he joined in 1952 after getting his law degree on the GI

bill, or at the helm of the big international development banks and law firms

where he spent the bulk of his Washington career.

"One of the things it taught you," he says of orphanage life, "was to

internalize your feelings, to surround yourself with walls and, above all,

never to show emotion or weakness."

That mental toughness was a critical survival tool in Furth, as Weiss had

the added disadvantage of being small for his age. "I was a shrimp," he

explains in the Holocaust Museum tapes. "I don't think I ever reached more

than 5-foot-4 or 5 inches. The Aryan race seemed a little better set up in our

neighborhood."

With his yarmulke and distinctive side-curls, Weiss was a natural target

for local bullies, particularly the young toughs from the Hitler Youth, who

were all too eager to practice on Jewish orphans what their adult leaders

preached. "Did you try to fight back?" the Holocaust Museum interviewer asks.

"I ran most of the time," Weiss replies. "But they'd still catch me sometimes

and beat the tar out of me."

It was from this unhappy vantage point that Weiss watched the Nazi

ascendancy. By the mid-1930s, the ranks of the orphanage had doubled, as

Jewish parents began disappearing into the growing network of Nazi prison

camps. Weiss vividly remembers the last time he saw his own father in 1935.

"He came to the orphanage, which was odd since I had not heard from him in

over two years. We went for a walk along the canal, and I remember he did

something very strange. He put his hands on my head and said a prayer. This

was very unusual because my father was not a religious man. 'We will probably

never see each other again,' he said, 'I'm going to try to leave Germany.'

That was the last I ever saw of him." Stefan Wangersheim was arrested soon

after visiting his son.

There were other ill omens that not even an 11-year-old could miss. By

1937, food at the orphanage had become scarce. The orphanage was financed by

Nuremberg's shrinking Jewish community, and as more and more Jews fled, were

arrested or had their businesses seized, there was less money available for

the orphans. "To earn a few extra marks, we were rented out at funerals to say

the mourner's prayer," Weiss recalls. "None of us particularly looked forward

to that."

At the same time, there was a massive influx of new students at Furth's

sole Jewish school, as Jews were expelled from all other academic

institutions. The transfers included Henry Kissinger and his younger brother,

who was in Weiss's class. (Kissinger many years later at a dinner party told

Weiss that, alas, he had no recollection of him.) By 1938, the orphanage's

ranks had almost tripled, and the children's diet was reduced mostly to

potatoes. Some of the kids' teeth started falling out from malnutrition, and

Weiss's gums and molars were badly weakened from vitamin deficiency.

Then one day in February 1938, salvation. Weiss was handed a cardboard

suitcase and told to pack. "You are going to America," he was informed. How

and why he, out of all the children at the orphanage, had been selected for

evacuation he does not know. Luck of the draw perhaps, or maybe the good will

of some distant family relation. How it was that Weiss was chosen for the

small American allotment was even more of a mystery, since compared with

Britain, Russia and other havens, the United States placed tight restrictions

on Jewish refugees.

Weiss didn't care about the whys and hows of his rescue. He just wanted

out. "Since I didn't have any real attachment to my mother or sisters anymore

because we had been apart for eight years, I saw this as a big adventure, and

was delighted to go."

The street smarts he had developed in Furth served him well in the United

States, where he landed to a decidedly frosty reception. He couldn't find a

place to live in New York when he got off the boat, and he was put on a train

to Chicago, where there were fewer refugees competing for homes. "We got into

Chicago at 3 a.m., and I noticed a train departing for Milwaukee," he

remembers. "I'd heard they spoke German there, so I got on it and locked

myself in the bathroom." In Milwaukee, he lived with the homeless at the train

station and ate in soup kitchens until the police picked him up. He was sent

to an orphanage, but kept running away. "I shined shoes and picked up a paper

route." Eventually a shop-owning family in the small town of Janesville, Wis.,

took him in. He went to high school and then watchmaker's college because his

foster father believed that everyone should have a trade. "That period was

among the happiest of my life," Weiss recalls. "I had a loving home and a

completely normal teenage existence, which I never took for granted."

The soldier who returned to Nuremberg in 1945 with the 45th division was a

different person from the refugee who had left seven years before. He had a

new name, for one, borrowed from the back of the jersey of a fleet-footed

University of Wisconsin football star; a new family back in Janesville; and a

new nationality and mother tongue, which he spoke with a flat Midwestern

accent. Nor was he a boy any longer, forced to run away from Nazi bullies. He

was a man, part of the most powerful army the world had ever seen, and it was

his turn to do the chasing.

Advancing through sniper-filled Nuremberg, Weiss barely recognized the city

he grew up in. Its narrow streets were too littered with rubble for U.S. tanks

to pass. The block where his parents had lived was a smoldering hulk; his old

orphanage stood silent and empty. Virtually everyone he had been close to was

dead: the stern but kind-hearted orphanage director, the kids he had bunked

with, the friends he had gone to school with. His uncles had shot themselves

rather than face deportation to the death camps. And his grandmother, the

person he was probably closest to in the whole world, the warm, loving woman

he would sneak out of the orphanage to visit, had been sent to the ghetto at

Theresienstadt in the Czech Republic, and then to Auschwitz in Poland to

become one of the 6 million.

His mother and sisters, at least, had managed to bribe their way out of

Germany, then to England and Portugal, and eventually, with Weiss's help, to

the United States. But Weiss had little time for reflection or sorrow. Orders

had come from 7th Army head-quarters for advance elements of the 45th to rush

to Dachau, to liberate the camp before a group of highly valued political

prisoners held there was moved or killed. (As Weiss recalls, the VIPs included

Leon Blum, the French prime minister; Austria's former chancellor; the deposed

head of state of Hungary; some bishops and cardinals; and a German relative of

the British royal family.) What he remembers most about Dachau, though, was

the smell. "I still have dreams about it," he says. A revolt had broken out in

the camp before the 45th's arrival, and while the SS retained control of parts

of the peri-meter, the crematoriums had not worked for some days. Bodies just

piled up, or lay decomposing between the long rows of low, wooden barracks.

Where SS guards still manned the watchtowers, near the main rail embankment,

an entire trainload of corpses rotted. "The SS had prevented anyone from

unloading it. The people locked inside the cattle cars slowly suffocated or

died of thirst," Weiss says.

Even though the camp was technically liberated, the prisoners were so weak

and skeletal that they perished at a rate of several hundred per day. Some

would crawl on their hands and knees to get outside through holes cut in the

barbed wire, so that they could die free. Others were "hell bent" on finding

and killing kapos, the club-wielding prisoner turnkeys who, in exchange for

extra rations, were as brutal as the SS guards they worked for. "Mobs would

descend on them and rip them limb from limb."

Weiss never found the prisoners his unit was sent to rescue. They had been

moved by the retreating German regular army, so that the SS would not

senselessly butcher potentially valuable bargaining chips. But sifting through

an unofficial record of Dachau's victims that had been secretly compiled by

prisoners since the mid-'30s and hidden in hollowed-out rafters, Weiss came

across a name he immediately recognized: Stefan Wangersheim, his father.

(Weiss would learn many years later that his father had survived and

immigrated to Brazil with a new wife. He died before Weiss had the chance to

reconnect with him.)

When the war ended, Weiss's real work began. The vast death machine Hitler

assembled had untold parts and myriad accomplices, and most of them did not

simply vanish with Hitler's suicide. The job of identifying and accounting for

those with the blood of millions on their hands would be neither quick nor

easy. Weiss had a daunting list of thousands of wanted Nazis to find. He

remembers one in particular, a man who had not even bothered to move from his

pre-war address or take on an assumed name. Weiss had simply looked him up in

the Munich phone book and knocked on his door early one morning in 1946.

Why the man had not bothered to conceal his tracks was a puzzle. Perhaps he

thought that after all these months no one would come looking for him. Or

maybe he believed he could hide beneath his low rank. He was an enlisted man;

there were plenty of bigger fish for the Americans to fry. But he had belonged

to the SS Death's Head, the notorious battalions tasked with liquidating

Europe's Jews, and Weiss, if he could help it, wasn't going to let the even

lowliest private from any of those killing squads go free.

"This guy was walking around Munich without a care while most of the people

I knew were dead," he says. "And at the time we still didn't even comprehend

the enormity of what they had done."

Of all branches of the SS, it was the Death's Head, and specifically its

Einsatzgruppen and sonderkomandos units, who ran the death camps and herded

entire villages into synagogues to be burned alive. They were the ones who dug

the mass burial pits on the outskirts of towns and dumped truckloads of earth

on women and children gasping for air. It was the Death's Head that was

responsible for devising ever more efficient ways of killing. At Auschwitz,

the pinnacle of their industriousness, they "processed" 60,000 people a day.

The man had been a guard at Auschwitz and Theresienstadt. It said so in his

military service ID record, which, astonishingly, he was still carrying when

Weiss nabbed him, as if these posts were somehow marks of distinction. Nor did

he make an effort to deny who he was or where he had worked, once Weiss had

him in a concrete cell flanked by two MPs.

"I had interrogated some very bad people," Weiss recalls, "but there was

something about this guy, an utter lack of remorse. He was oblivious, like

he'd done nothing wrong."

The man was in his mid-forties, unshaven and pale. He'd been drunk when

Weiss picked him up, but two days in the cell had sobered him up sufficiently

for the realization to start dawning that he was in trouble. It was clear to

Weiss that the man had probably never gotten beyond elementary school, and his

German was of the guttural Bavarian dialect spoken throughout the lowest ranks

of the blue-collar class.

Weiss says he spent less than an hour in the cell, getting the information

he needed: names of superiors, other guards and so on. "I just wanted to get

out of there and take a shower.

"I guess what got me was the complete absence of humanity. To him,

Auschwitz had just been a job. The fact that more than a million people were

killed there didn't seem to faze him in the least bit. He didn't see Jews as

people."

Weiss thought of his father, his friends at the orphanage, his grandmother.

The SS man had worked at the same two camps where she had been sent. He was

only a lowly cog in the killing machine, and that meant he was of little value

to intelligence headquarters in Frankfurt. Unlike Zander, he didn't have to be

kicked up the intelligence food chain. In that sense, the man had been right

about not needing to go into hiding. No one at Allied Command was particularly

interested in someone of his status. But if he believed that his low rank

would somehow spare him from justice, he was dead wrong.

Weiss used Jewish killers

|

"How did you do it?" I ask

Weiss. "The kapos," he explains, "that's where we got the idea. We had

seen what the DPs did to the kapos, and we realized they could do us a

favor."

DPs, or displaced persons,

were the survivors of death and POW camps -- Jews, Poles, Russians,

Hungarians, refugees of virtually every nationality who either could not

return home or no longer had any homes to return to. They numbered in

the hundreds of thousands in Europe, and they were housed in huge

temporary DP camps. Several such refugee camps, converted German Army

barracks, were near Munich.

"We studied up a little on

military law, and there was nothing on the books preventing us from

delivering suspects for additional debriefing to the DPs," Weiss

recalls. He says he's not sure where the idea originated, who first put

it into motion, or how widespread it was. "Whoever first came up with

this, I honestly don't know. I don't think they'd own up to it anyway.

|

"

|

|

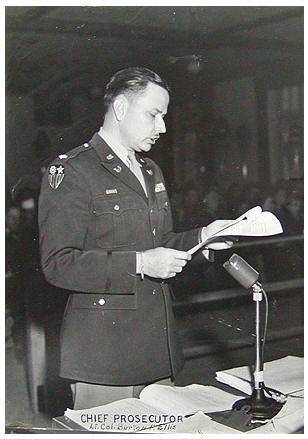

Oven

While it was

perfectly legal

under military law to hand over suspects for further questioning to DPs,

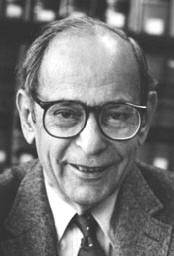

says Benjamin Ferencz, who was a lead U.S. prosecutor at the Nuremberg

War Crimes Tribunals in 1945 and 1947, knowingly delivering suspects for

execution was not. And of course the DPs were not interested in

extracting information.

Ferencz, who today is 85 and

lives in New York, cautions against making sweeping armchair moral

judgments. "Someone who was not there could never really grasp how

unreal the situation was," he says.

"I once saw DPs beat an SS man and

then strap him to the steel gurney of a crematorium. They slid him in

the oven, turned on the heat and took him back out. Beat him again, and

put him back in until he was burnt alive. I did nothing to stop it. I

suppose I could have brandished my weapon or shot in the air, but I was

not inclined to do so. Does that make me an accomplice to murder?"

|

Ferencz -- who went on to a distinguished legal career, became a founder of

the International Criminal Court and is today probably the leading authority

on military jurisprudence of the era -- cannot specifically address Weiss's

actions. But he says it's important to recall that military legal norms at the

time permitted a host of flexibilities that wouldn't fly today. "You know how

I got witness statements?" he says. "I'd go into a village where, say, an

American pilot had parachuted and been beaten to death and line everyone one

up against the wall. Then I'd say, 'Anyone who lies will be shot on the spot.'

It never occurred to me that statements taken under duress would be invalid."

Weiss says that his unit had its

own system of ethics when it came to handing former death camp guards over to

the DPs.

"You couldn't do that by yourself," he says. "You consulted with the

other CIC agents, and usually there was a duty officer. We would have never

done this," he adds, "without at least some nod from a superior."

The key was to make certain that there were no cases of mistaken identity.

The SS men would have to own up to their participation in mass murders of

their own volition, never as a result of torture, since people tend to admit

to anything under such circumstances, says Weiss. As a backup, "I'd make them

write out a detailed history of their war record, including who they served

with, when and under who." This was double-checked against captured Nazi

records to make sure that the person was indeed who they claimed to be. Only

then was the decision taken, Weiss says.

Took prisoners to DP camps for execution

|

Weiss remembers the panic in

the SS men's eyes when they finally realized where they were being

taken. "We never told

them where they were going," he says. At the sight of the old German

Army barracks, they grasped their fate. Some would try to cling to the

jeep, but the reception committee would forcibly remove them. Weiss says

he never looked back in the rearview mirror to see what happened next.

Nor did he need to.

In all, Weiss recalls being

involved in about a dozen such cases. There were similar instances in

other CIC units, Weiss says, but he does not know the circumstances of

those cases or how many there were.

Weiss says he no longer remembers

most of the names of those handed over to the DPs, and that even if he

did, he would not divulge them because their descendants might seek

recourse.

|

He says he has never,

however, had any moral qualms about his actions. "I never gave it much

thought after the war," he says. "The point is: What do you do with

these guys? The war crimes courts were already backlogged with more

senior Nazis. The jails were full. They were going to slip through the

cracks."

|

The overwhelming majority of the lower-level SS guards did in fact escape

justice.

Ferencz prosecuted members of the Einsatzgruppen. "There were 3,000 members

of these killing squads who did nothing but kill women and children for three

straight years," he says. "These 3,000 men alone were responsible for almost 1

million murders. Do you know how many I brought indictments against?

Twenty-two. The rest were never tried.

"I remember talking to Soviet officers," he adds. "And they were baffled.

'You know they're guilty,' they'd say. 'Why don't you just shoot them?' There

was a lot of that kind of feeling in postwar Germany."

Weiss, for his part, says he never went to Germany bent on revenge.

"Whatever anger I might have had was dissipated by the devastation and

destruction I witnessed of German society. The German people paid dearly for

their infatuation with Hitler. But there were times when justice just had to

be done."

Matthew Brzezinski last wrote for the Magazine about a Chechen rebel

leader. He will be fielding questions and comments about this article Monday

at 1 p.m. at washingtonpost.com/liveonline.

This is yet another example of the

irrationality of David Irving. He simply cannot grasp that Peter Stahl and

Gregory Douglas are two different persons. Also, the author of this article does

not know Konrad Kujau, has not helped the Swiss authorities

against anyone, and does not live in Freeport, Illinois. Also, I did

not assassinate Abraham Lincoln, assist in the sinking of the Titanic nor

was I a lead pilot in the Pearl Harbor attack. Where Irving comes up with these

fictions quite escapes me.

The only reason that I can determine

that could possibly explain his prolonged hysteria concerning myself is that

some years ago, I bought a collection of the correspondence between Adolf Hitler

and Eva Braun. These letters were in the Schloss Fischhorn collection and came

from a Eugene

Frankenfeld

of Philadelphia.

Frankenfeld was a

CIC

operator that was part of a team that discovered the papers of Hermann Fegelein

that were buried at the SS Riding

School run by his brother, Waldemar. Instead of turning these letters, and other

important historical papers, in to the U.S. Army authorities,

Frankenfeld

kept many of them and sold them off to various collectors

New Missions

CIC's overseas mission did not end with the conclusion of hostilities. It

served as the Army's chief agency in occupied Austria, Germany, and Italy,

rounding up individuals subject to "automatic arrest" because of their Nazi

affiliations or activities. At the same time, CIC was on the lookout for a

resurgent underground Nazi movement as well as efforts to circumvent Allied

occupation directives. CIC spent a considerable amount of time handling problems

associated with thousands of displaced persons in Western Europe as well as

ensuing black market activities. By 1946, the 970th CIC Detachment

(later designated as the 7970th CIC Detachment in 1948 and then as

the 66th CIC Detachment in 1949) in Germany and the 430th

CIC Detachment in Austria handled the bulk of the early post-war CIC operations.

When Mahl was interrogated by Michel Thomas, a Jewish

agent with the US Counter Intelligence Corps, in early May 1945, he made a

handwritten statement in which he confessed that, as the executioner of the

camp, he had hanged 800 to 1,000 people including a pregnant woman.

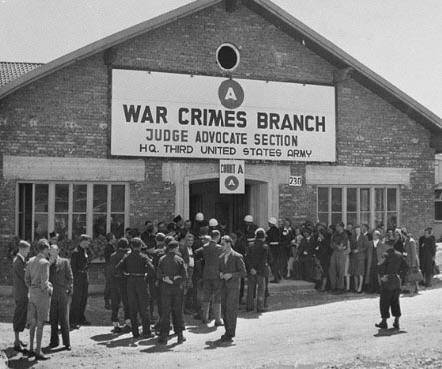

Dachau Trials

Introduction

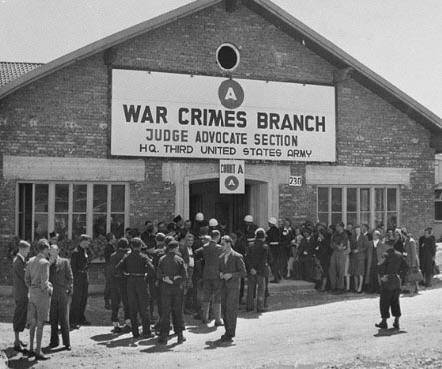

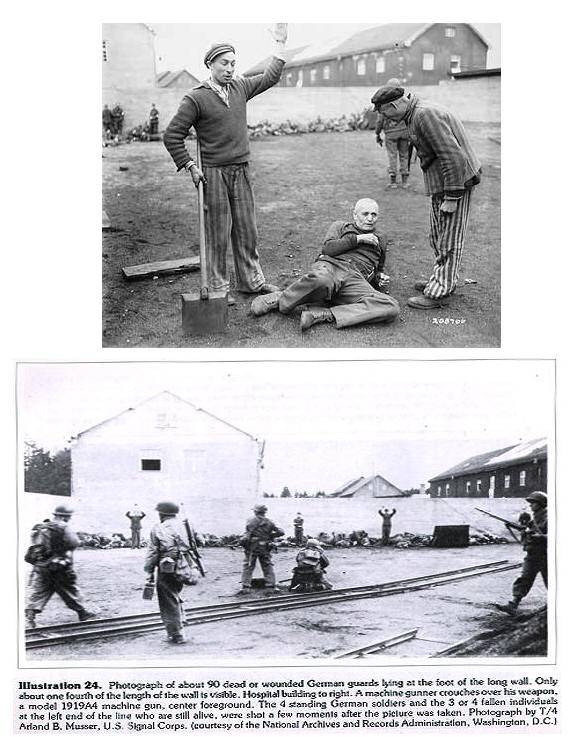

Although most Americans are familiar with the

Nuremberg International Military Tribunal, at which 22 top-level German war

criminals were prosecuted after World War II ended, few people today are

aware that there were many other Military Tribunal proceedings going on

simultaneously in a building inside the former Dachau concentration camp.

The "Dachau trials" were conducted by the American military specifically to

punish the administrators and guards at the concentration camps that were

liberated by American soldiers and to educate the public about the

unbelievable atrocities committed in these horror camps.

Between November 1945 and August 1948, there were

489 cases brought before the American Military Tribunal at Dachau. There was

a total of 1,672 persons who were tried and 1,416 of them were convicted.

There were 297 death sentences, and 279 sentences to life in prison. These

1,672 war criminals who faced the American Military Tribunal at Dachau had

been selected from a group of 3,887 people who were initially accused. The

last of those who were not put on trial were finally released from their

imprisonment at Dachau in 1948. |

http://www.humanitas-international.org/archive/dachau-liberation/

The

Wannsee

Conference Protocol:

Anatomy of a Fabrication

by Johannes Peter

Ney

"WANNSEE

CONFERENCE: conference of chief representatives of the highest Reich and Party

bodies, held on January 1, 1940 in Berlin at 'Am Großen

Wannsee

56/58' under the chairmanship of R. Heydrich. On the order of A. Hitler, the

participants decided on measures for the annihilation of the Jews in those

parts of Europe under German control ('Final Solution of the Jewish

Question'): the establishment of extermination camps (concentration camps) in

Eastern Europe, where Jews were to be killed." (1)

1.

On Document Criticism

Documents are objects containing

encoded information about a process or condition. For example, one

differentiates between photographic and written documents as well as, recently,

between all kinds of data storage (sound carriers, electronic data carriers, and

many more). The present discussion will focus on the criticism of written

documents, which represent the main of the documents relating to the Holocaust.

If a document is to prove anything, it is first necessary to establish that the

document is genuine and the information it contains is factually correct. The

authenticity of a document requires, for one thing, that the materials and

techniques of information encoding and storage involved already existed at the

alleged time of document creation. Today, technical, chemical and physical

methods frequently permit the verification of whether the paper, the ink, the

writing tools etc. that make up the document or went into its production even

existed at the alleged time of creation. If this is not the case, the document

has been proven to be fake. For example, a document allegedly dating from the

1800s but typed on a typewriter from our own century would definitely be a fake.

Unfortunately this kind of analysis is not generally possible where the items to

be analyzed are Holocaust documents, since in those few cases where original

documents are known to exist, these originals are jealously guarded in archives

and any attempt at scientific and technical analysis is nipped in the bud.

Another element in the verification of authenticity is the determination of

whether the form of the document at issue corresponds with that of similar

documents of the same presumptive origin. For handwritten documents this means a

similarity of handwriting and style of expression to other documents by the same

author, while for official documents it requires the congruence of official

markings identifying the issuing body, such as letterheads, rubber stamps,

signatures and initials, reference numbers, titles and official names, notices

of receipt, distributors, correctness of the administrative channels and

authority etc., as well as, again, similarity to the regional and bureaucratic

style of expression. The greater the discrepancies, the more likely it is that

the document is a fabrication.

And finally, it must also be determined whether the contents of the document are

factually correct. One aspect of this is that the conditions and events

described in the document must agree with the information we already have from

other reliable sources. But the fundamental question is whether what is

described in the document is physically possible, and consistent with what was

technically feasible at the time and whether the contents are internally logical

and consistent. If this is not the case, the document may still be genuine, but

its contents are of no probative value, except perhaps where the incompetence of

its author is concerned.

Concerning document criticism in the context of the Holocaust, we encounter the

remarkable phenomenon that any such practice is dispensed with almost entirely

by the mainstream historians around the world. Even a call for impartial

document criticism is considered reprehensible, since this would admit the

possibility that such a document might be false, in other words, that certain

events which are backed up by such documents may not have taken place at all, or

not in the manner described to date. But nothing is considered more

reprehensible today than to question the solidly established historical view of

the Holocaust. However, where doubts about scientific results are deemed

censurable, where the questioning of one's own view of history or perhaps even

of the world is forbidden, where the results of an investigation must be

predetermined from the start, i.e. where research may produce only the 'desired'

results--where such conditions prevail, the allowed or allowable lines of

inquiry have long since forsaken any foundation in science and have instead

embraced religious dogma. Doubt and criticism are two of the most important

pillars of science.

The present volume contains many instances of criticism of a wide range of

documents, frequently proving them to be fabrications. No one will deny that

particularly after the end of World War Two a great many forgeries were produced

in order to incriminate Germany.(2 ) That opportunities for such forgeries were

practically limitless is a fact also undisputed in view of all the captured

archives, typewriters, rubber stamps, stationery, state printing presses etc.

etc. And considering these circumstances, no one can rule out beforehand that

the subject of the Holocaust may also have been the object of falsifications.

Unconditionally honest document criticism is thus vitally important here. In the

following, the

Wannsee Conference Protocol --the

central piece of incriminating evidence pertaining to the Holocaust--is

subjected to an in-depth critical analysis such as all historians worldwide

ought to have done for decades but failed to do. At the same time, this analysis

may serve as challenge to all conscientious historians to finally subject all

Holocaust documents --be they incriminating or exonerating-- to professionally

correct and unbiased document criticism.

2. The Material About the

Wannsee

Conference

2.1

Primary Sources - the Material to be Analyzed

In any analysis of the

Wannsee

Conference Protocol, the other documents directly related to this Protocol must

of course be considered as well. These documents are:

1)

Göring's

letter of July ?, 1941 to

Heydrich, instructing

Heydrich

to draw up an outline for a total solution of the Jewish question in

German-occupied Europe.

2) Heydrich's

first letter of invitation to the

Wannsee

Conference, dated November 29, 1941.

3) Heydrich's

second invitation to the

Wannsee

Conference, dated January 8, 1942.

4) The Wannsee

Conference Protocol itself, undated.

5) The letter accompanying the

Wannsee

Conference Protocol, dated January 26, 1942.

According to his own

statements,(3 )

Robert

M. W.

Kempner,

the prosecutor in the

Wilhelmstraßen Trial of Ernst

Weizsäcker,

had been expecting a shipment of documents from Berlin in early March 1947.

Among these papers, he and his colleagues discovered a transcript of the

Wannsee

Conference. The author of the

protocol, it was claimed, was

Eichmann. In 1983 the

WDR

(West German Radio) broadcast

Kempner's

original taped statement, according to which he had discovered the protocol in

autumn of 1947.(4) Beyond

Kempner's

verbal statements quoted here, no other

documentation verifying the place and circumstances of the discovery were found.

Kempner:

"Of course no one doubted the authenticity [of the protocol]." The Court, he

said, introduced the protocol as Number 2568. In the court records it appears as

G-2568.

2.1.2 Different

Versions

The Wannsee

Conference Protocol which

Kempner

submitted to the Court always writes 'SS' in this way, i.e. in Latin letters,

not as the runic '[..]' which was customary in the Third Reich. It would appear

to be the oldest copy in circulation.(5)

Hans Wahls

has mentioned numerous other versions which are also in circulation. The

Political Archives at the Foreign Office in Bonn maintains that the version held

there is the definitive one. This version uses the runic '[..]'. When and how

this version came to be in the archives of today's Foreign Office remains

unknown. Since the other versions can also not be traced back to their origins,

we will dispense with any further details here. The present compilation is thus

based only on the copy held by the Foreign Office.(6)

Where the letter accompanying the protocol is concerned, two versions have

surfaced to date, one using 'SS', the other with the runic '[..]' as well as

other differences.

2.2

Secondary Sources - Literature About the

Wannsee

Conference Protocol

The literature pertaining to the

Wannsee

Conference Protocol fills many volumes. The following summarizes the most

important analyses and critiques, all of which prove conclusively that all the

various versions of the protocol as well as all the versions of the letters

accompanying the protocol are fabrications. As yet, no proof of the authenticity

of the protocol, nor any attempt at refuting the aforementioned analyses and

critiques, has been advanced by any source.

This discussion draws on:

Hans

Wahls,

Zur

Authentizität

des 'Wannsee-Protokolls';(7)

Udo

Walendy,

"Die Wannsee-Konferenz

vom

20.1.1942";(8)

Ingrid Weckert,

"Anmerkungen

zum

Wannseeprotokoll";(9)

Johannes Peter Ney,

"Das

Wannsee-Protokoll";(10)

Herbert Tiedemann, "Offener

Brief an Rita Süßmuth".(11)

Other important studies shall just be mentioned briefly.(12)

3. Document Criticism

3.1 Analysis of the Prefatory

Correspondence

3.1.1 Göring's

Letter (13)

Form: We only have a copy of this document, as no original has ever been found.

This copy is missing the letterhead, the typed-in sender's address is incorrect,

and the date is incomplete, missing the day.(14) The letter has no reference

number, no distributor is given, and there is no line with an identifying 're.:'

(cf. Ney(10)).

Linguistic content: The repetition in "all necessary preparations as regards

organizational, factual, and material matters" and "general plan showing the

organizational, factual, and material measures" is not

Göring's

style, and is beneath his linguistic

niveau.(15)

The same goes for the expression "möglichst

günstigsten

Lösung"

[grammatically incorrect, intended to mean "best possible way"].(16)

3.1.2 The First Invitation (17)

Form: The classification notice "top secret" is missing (cf. Ney10 and

Tiedemann11). It is also strange that the letter took 24 days, from November 29,

1941 to December 23, 1941, for a postal route within Berlin (Ney(10)).

Linguistic content: "Fotokopie"

was spelled with a 'ph' in those days; the spelling that is used is strictly

modern German. "Auffassung

an den [...] Arbeiten"

(@"opinion on the [...] tasks") is not proper German; it ought to read "Auffassung

über

die [...] Arbeiten".

"Persönlich"

["personal"] was scorned as classification; the entire style of the letter is

un-German (Ney,

ibid.).

3.1.3 The Second Invitation (18 )

Form: This document exists only in

copy form, no original has ever been found. The letter bears the issuing

office's running number "3076/41", while the letter accompanying the protocol,

dated later, bears an earlier number, "1456/41" (Tiedemann(11)). The letterhead

is different from that of the first invitation (Tiedemann, ibid.). The letter is

marked only as "secret" (Ney(10)).

Linguistic content: On one occasion the letter "ß" is used correctly ("anschließenden"),

but then "ss"

is used incorrectly ("Grossen").

(Ney,

ibid.)

Stylistic howlers: "Questions pertaining to the Jewish question"; "Because the

questions admit no delay, I therefore invite you...." (Ney,

ibid.)

3.2 Analysis of the

Wannsee

Conference Protocol

3.2.1 Form

While it is claimed that the copy of

the Wannsee

minutes held by the Foreign Office is the original, this cannot in fact be the

case, since it is identified as the 16th copy of a total of 30. Regardless

whether it is genuine or fake, however, its errors and shortcomings as to form

render it invalid under German law, and thus devoid of documentary value:

The paper lacks a letterhead; the issuing office is not specified, and the date,

distributor, reference number, place of issue, signature, and identification

initials are missing (Wahls(7) and Walendy(8)). The stamp with the date of

receipt by the Foreign Office, which is (today!) named as the receiver, is

missing (Tiedemann(11)). The paper lacks all the necessary properties of a

protocol, i.e. the minutes of a meeting: the opening and closing times of the

conference, identification of the persons invited but not attending (Tiedemann,

ibid.), the names of each of the respective speakers, and the countersignature

of the chairman of the meeting (Tiedemann, ibid., and Ney(10)). The paper does,

however, bear the reference number of the receiving(!) office, namely the

Foreign Office - typed on the same typewriter as the body of the text

(Tiedemann(11)). The most important participant,

Reinhard

Heydrich,

is missing from the list of participants (Wahls(7) and Walendy(8)).

3.2.2 Linguistic Content

The

Wannsee

Conference Protocol is a treasure-trove of stylistic howlers which indicate that

the authors of this paper were strongly influenced by the Anglo-Saxon i.e.

British English language. In the following we will identify only the most

glaring of these blunders; many of them have been pointed out by all the authors

consulted, so that a specific reference frequently does not apply.

The expressions "im

Hinblick"

("considering",* 8 times), "im

Zuge"

("in the course of", 5 times), "Lösung"

("solution", 23 times), "Fragen"

("questions", 17 times), "Problem" (6 times), "Bereinigen"

("to clarify", 4 times), frequently even more than once in the same sentence,

bear witness to such a poor German vocabulary that one may assume the author to

have been a foreigner.

Further, the expressions "Lösung

der

Frage"

("solution of the problem"), "der

Lösung

zugeführt"

("brought near to a solution"), "Lösungsarbeiten"

("tasks involved" [in a solution; -trans.]), "Regelung

der

Frage"

("to settle the question"), "Regelung

des Problems" ("to settle the problem"), "restlose

Bereinigung

des Problems" ("absolutely final clarification of the question" [i.e. the

"problem"; - trans.]), "Mischlingsproblem

endgültig

bereinigen"

("securing a final solution of the problem presented by the persons of mixed

blood"), "praktische

Durchführung"

("practical execution"; is there such a thing as a theoretical execution?), and

especially the frequent repetition of these expressions, are not at all the

German style (Walendy(8)).

The phrase;

"der

allfällig

endlich

verbliebene

Restbestand

[...]" ("the possible final remnant")

may perhaps appear in a prose text, but certainly not in the minutes of a

conference. The text is interspersed with empty phrases such as;

"Im

Hinblick

auf die Parallelisierung

der

Linienführung"

("in order to bring general activities into line") (Tiedemann(11))

and nonsensical claims such as;

"Die

evakuierten

Juden

werden

Zug um Zug in [...]

Durchgangsghettos

gebracht

[...]" ("The evacuated Jews will first be sent, group by group, into [...]

transit-ghettos [...]").

Since the evacuation of the Jews was not then ongoing, but rather was planned

for the future, this would have to have read:

"Die

zu

evakuierenden

Juden

[...]" ("The Jews to be evacuated [...]").

Further:

"Bezüglich

der

Behandlung

der

Endlösung"

("Regarding the handling of the final solution")

How does one handle a solution? (Walendy(8))

"Wurden

die jüdischen

Finanzinstitutionen

des Auslands

[...] verhalten

[...]"

Does the author mean "angehalten"?*

"Italien

einschließlich

Sardinien"

("Italy incl. Sardinia")

Why the need to specify? In Europe people knew very well what all was part of

Italy.

"Die

berufsständische

Aufgliederung

der

[...] Juden:

[...] städtische

Arbeiter

14,8%" ("The breakdown of Jews [...] according to trades [...]: [...] communal

workers 14.8%" [i.e. "municipal" workers; -trans.]

Were all of these people common laborers? (Ney(10)) "Salaried employees" is

probably what the author meant here. "[...]

als

Staatsarbeiter

angestellt"

(the Nuremberg Translation renders this as "employed by the state", which

glosses over the difference between "Arbeiter",

i.e. blue-collar workers, and "angestellt",

i.e. the condition of employment enjoyed by salaried and public employees;

-trans.): so what were they, laborers or government employees? Did the author

mean civil servants? (Ney,

ibid.)

"In den

privaten

Berufen

- Heilkunde,

Presse,

Theater, usw."

("in private occupations such as medical profession, newspapers, theater,

etc.").

In German these are called "freie

Berufe",

not "private Berufe".

Such persons are known as doctors, journalists, and artists. "usw."

is never preceded by a comma in German, whereas the English "etc." almost always

is.

"Die

sich

im

Altreich

befindlichen

[...]"

Well, German is a difficult language. (Ney,

ibid.)

3.2.3 Contradictory Content

"[...]

werden

die [...] Juden

straßenbauend

in diese

Gebiete

geführt":

literally, "the Jews will be taken to these districts, constructing roads as

they go".

Migratory road crews?! Not a single road was constructed in this fashion!

(Wahls(7) and Walendy(8))*

"Im

Zuge

dieser

Endlösung

[...] kommen

rund

11 Millionen

Juden

in Betracht."

("Approx. 11,000,000 Jews will be involved in this final solution [...]."

Even the orthodox prevailing opinion holds that there were never more than 7

million Jews in Hitler's sphere of influence. In actual fact there were only