|

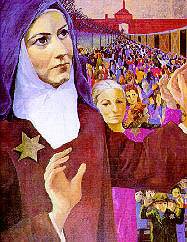

Edith Stein [1891-1942] |

|

|

Edith Stein [1891-1942] |

|

Reconstructed by Marianne Sawicki. Updated 9 November 1998. (Please send

corrections to

sawicki@morgan.edu)

Eighteen volumes of the series Edith Steins Werke have appeared since 1950. The current publisher is Herder in Freiburg. Volume 10 is a biography of Stein by Romaeus Leuven.

Five volumes have appeared in the English translation series, The Collected Works of Edith Stein. The publisher is the Institute of Carmelite Studies, 2131 Lincoln Road NE, Washington, D.C. 20002-1199.

Stein's four major phenomenological treatises are indicated below in

boldface type. None of these treatises has yet appeared in a critical

edition in ESW.

| 1914 | "Husserls Exzerpt aus der Staatsexamensarbeit von Edith Stein." Edited by Karl Schuhmann. Tijdschrift voor Filosofie 53 (1991) 686-699. |

| 1916 | Zum Problem der Einfühlung. Halle: Buchdrucheri des Waisenhauses, 1917. Reprinted Munich: Kaffke, 1980. On the Problem of Empathy. Translated by Waltraut Stein. Third revised edition. CWES 3 (1989). |

| 1917 | "Zur Kritik an Theodor Elsenhans und August Messer." Aufsätze und Vorträge (1911-1921), 226-248. Husserliana 25 (1987). |

| "Zu Heinrich Gustav Steinmanns Aufsatz 'Zur systematischen Stellung der Phänomenologie'." Aufsätze und Vorträge (1911-1921), 253-266. Husserliana 25 (1987). | |

| 1919 | "Psychische Kausalität." Beiträge zur philosophischen Begründung der Psychologie und der Geisteswissenschaften, Erste Abhandlung. Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung 5 (1922) 1-116. Reprinted Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1970. [This was intended as Stein's Habilitationsschrift for Göttingen. Translation due out next year in CWES.] |

| 1920 | "Individuum und Gemeinschaft." Beiträge zur philosophischen Begründung der Psychologie und der Geisteswissenschaften, Zweite Abhandlung. Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung 5 (1922): 116-283. Reprinted Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1970. [Translation due out next year in CWES.] |

| Review of Naturerlebnis und Wirklichkeitsbewußtsein, by Gertrud Kutznizky. Kant-Studien 24/4 (1920): 402-405. | |

| "Vorwort" and commentary. Adolf Reinach: Gesammelte Schriften, 406 and passim. Halle: Neimeyer, 1921. | |

| 1921 | "Eine Untersuchung über den Staat." Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung 7 (1925): 1-123. Reprinted Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1970. [Translation due out soon in CWES.] |

| 1924 | "Was ist Phänomenologie? Wissenschaft/Volksbindung - Wissenschaftliche Beilage zur Neuen Pfälzischen Landes-Zeitung 5 (May 15, 1924). Reprinted in Theologie und Philosophie 66 (1991) 570-573. |

| 1928 | John H. Kardinal Newman: Briefe und Tagebücher 1801-1845. Translated by Edith Stein. Munich: Theatinerverlag. |

| 1929 | "Husserls Phänomenologie und die Philosophie des hl. Thomas v. Aquino: Versuch einer Gegenüberstellung." Jahrbuch für Philosophie und phänomenologische Forschung. Erganzungsband, 315-338. Husserl's Phenomenology and the Philosophy of St. Thomas Aquinas: Attempt at a Comparison. Translated by Mary Catharine Baseheart. Persons in the World: Introduction to the Philosophy of Edith Stein, 129-144 and 179-180. By Mary Catharine Baseheart. Dordrecht: Kluwer, 1997. |

| "Was Ist Philosophie? Ein Gespräch zwischen Edmund Husserl und Thomas von Aquino." ESW 15 (1993) 19-48. [Apparently this was the first draft for the 1929 Jahrbuch but had to be redone at the insistence of Martin Heidegger.] | |

| "Die Typen der Psychologie und ihre Bedeutung für die Pädagogik," Zeit und Schule 26: 27-28. ESW 12 (47-51). | |

| 1930 | "Die theoretischen Grundlegen der sozialen Bildungsarbeit," Zeit und Schule 27: 81-85, 90-93. ESW 12 (52-74). |

| "Zur Idee der Bildung," Zeit und Schule 27: 159-167. ESW 12 (1990) 25-37. | |

| 1931 | "Der Intellekt und die Intellektuellen," Das heilige Feuer 18: 193-8, 269-72. Reprinted in Edith Stein Wege zur inneren Stille, 98-117. Edited by Waltraud Herbstrith. Aschaffenburg: Kaffke, 1987. |

| "Potenz und Akt." Typescript, later expanded into Endliches und ewiges Sein. ESW 18 (1998). [This was intended as Stein's second Habilitationsschrift, for Freiburg.] | |

| "Aktuelles und ideales Sein - Species - Urbild und Abbild." (Fragment) ESW 15 (1993) 57-63. | |

| Einführung in die Philosophie. ESW 13 (1991). [This seems to be lecture material prepared in 1931. However, the condition of the manuscript suggests that portions of the material now appearing on pages 141-224 were composed about 1920. The editor characterizes this work as a third Habilitationsschrift, intended for Breslau.] | |

| 1932 | Des hl. Thomas von Aquino Untersuchungen über die Wahrheit (Questiones disputate de veritate). Two volumes. Translated by Edith Stein. Breslau: Otto Borgmeyer. Second edition, with Latin-German glossary, 1934. Reprinted as ESW 3 (1952) and 4 (1955). |

| Der Aufbau der menschlichen Person. ESW 16 (1994). [Lectures delivered in Münster.] | |

| "Die ontische Struktur der Person und ihre erkenntnistheoretische Problematik." ESW 6 (1962) 137-197. | |

| "Die weltanschauliche Bedeutung der Phänomenologie." ESW 6 (1962) 1-17. | |

| "Natur und Übernatur in Goethes 'Faust'." ESW 6 (1962) 19-31. | |

| "Husserls transcendentale Phänomenologie." ESW 6 (1962) 33-35. | |

| "Erkenntnis, Wahrheit, Sein." ESW 15 (1993) 49-56. | |

| Texte originel des interventions de Mlle. Stein. La Phénoménologie. Journée d'études de la Société thomiste, Juvisy, 101-9. | |

| 1933 | Review of Die Abstraktionslehre des hl. Thomas von Aquin, by L.M. Habermehl. Philosophisches Jarhbuch der Görres-Gesellschaft 46: 502-3. |

| "Karl Adam's Christusbuch." Die Christliche Frau (Münster), March, 1933: 84-89. | |

| Was ist der Mensch? Eine theologische Anthropologie. ESW 17 (1994). | |

| 1928-33 | "Probleme der Frauenbildung," "Das Bildungsmaterial," "Das Ethos der Frauenberufe," "Lebensgestaltung im Geist der hl. Elisabeth," "Beruf des Mannes und der Frau nach Natur und Gnadenordnung." Frauenbildung und Frauenberufe. München: Schell & Steiner, 1949. Expanded edition: Die Frau: Ihre Aufgabe nach Natur und Gnade. ESW 5 (1959). Essays on Woman. Translated by Freda Mary Oben. CWES 2 (1987). [The last essay in this volume, "Challenges Facing Swiss Catholic Academic Women," was not written by Edith Stein; see Josephine Koeppel, Edith Stein Philosopher and Mystic (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1990), 181. Additional essays from this period are translated by Freda Mary Oben in An Annotated Edition of Edith Stein's Papers on Woman. Doctoral dissertation, The Catholic University of America, 1979.] |

| 1933-35 | Aus dem Leben einer jüdischen Familie. Das Leben Edith Steins: Kindheit und Jugend. ESW 7 (1965). Reprinted as Aus meinem Leben. Mit einer Weiterführung über die zweite Lebenshälfte von Maria Amata Neyer OCD. Freiburg: Herder, 1987. Life in a Jewish Family: Her Unfinished Autobiographical Account. CWES 1 (1986). Translated by Josephine Koeppel. |

| 1934 | "Die deutsche Summa." Die christliche Frau (Münster) 32 (August-September 1934) 245-252 and (October 1934) 276-281. |

| 1935-36 | Endliches und ewiges Sein: Versuch eines Aufstieges zum Sinn des Seins. ESW Werke 2 (1950; second edition, 1962; third edition, 1986). [Translation due out soon in CWES.] |

| "Die Seelenburg." [Originally an appendix to Endliches und ewiges Sein, but deleted by the publisher.] ESW 6 (1962) 39-68. | |

| "Martin Heideggers Existentialphilosophie." [Originally an appendix to Endliches und ewiges Sein, but deleted by the publisher.] ESW 6 (1962) 69-135. [This volume of ESW also contains two short discussions of Husserl.] | |

| "Entwurf eines Vorworts zu Endliches und ewiges Sein." (Fragment) ESW 15 (1993) 63-64. | |

| 1935-41 | Verborgenes Leben: Hagiographische Essays, Meditationen, geistliche Texte. ESW 11 (1987). The Hidden Life: Hagiographic Essays, Meditations, Spiritual Texts. CWES 4 (1992). Translated by Waltraut Stein. |

| Ganzheitliches Leben: Schriften zur religiösen Bildung. ESW 12 (1990). | |

| 1937 | Review of "La crise de la science et de la philosophie transcendentale. Introduction à la philosophie phénoménologique," by Edmund Husserl. Revue Thomiste (May-June 1973) 327-329. |

| 1940-41 | "Wege der Gotteserkenntnis: Die 'symbolische Theologie' des Areopagiten und ihre sachlichen Voraussetzung." ESW 15 (1993) 65-127. "Ways to Know God," translated by M. Rudolf Allers, The Thomist 9 (July 1946) 379-420. Reprinted in New York by the Edith Stein Guild, 1981. |

| 1942 | Kreuzeswissenschaft: Studie über Joannes a Cruce. ESW 1 (1954; second edition, 1983). The Science of the Cross: A Study of St. John of the Cross. Translated by Hilda Graef. London: Burns & Oates, 1960. [New translation expected next year in CWES will incorporate more recent scholarship on John of the Cross.] |

| 1916-42 | Selbstbildnis in Briefen. Part 1: 1916-1934. ESW 8 (1976). Part 2: 1934-1942. ESW 9 (1977). [Includes some letters to Ingarden and all letters to Conrad-Martius, although these have also been published separately.] Self-Portrait in Letters: 1916-1942. Translated by Josephine Koeppel. CWES 5 (1993). |

| Breife an Roman Ingarden 1917-1939. ESW 14 (1991). | |

| Briefe an Hedwig Conrad-Martius. Munich: Kösel, 1960. | |

The Spanish philosopher, José Ortega y

Gasset, once compared generations to travellers along a highway. Most people

prefer to travel in a caravan, seeking safety by pitching their tents close to

their neighbours. A few travel ahead, and some lag behind. Edith Stein was one

of those who travelled ahead.

Her journey began in the city of Breslau in Germany (now Wroclaw, Poland) on the

most sacred day of the Jewish Calendar–Yom Kippur–October 12, 1891. Her father,

Siegfried Stein, was a lumber merchant who died when Edith was three years old.

Edith’s mother, Auguste Stein (neé Courant) took over the management of the

family business, while raising seven children. Edith was the youngest. She was

especially close to her sister Erna, two years older than she. Edith and Erna,

the two youngest, were nicknamed the “afterthoughts”, and were doted on by the

other family members. Yet the two sisters were quite different. Erna was said to

be “as transparent as a glass of water”, while Edith–introspective, aloof–was

likened to “a book with seven seals”.

With a brilliant mind and vivid imagination, Edith did well in school, despite

dropping out for two years. After graduating from the gymnasium, she

decided to pursue a teaching career and enrolled at the University of Breslau.

Yet she was clearly seeking answers, some of them (she later realised) of a

religious nature. Years later, Edith

recalled that between the ages of 13 and 21, she could not believe in the

existence of a personal God. Perhaps psychology, then emerging as a new science,

could provide the explanations she sought.

With a brilliant mind and vivid imagination, Edith did well in school, despite

dropping out for two years. After graduating from the gymnasium, she

decided to pursue a teaching career and enrolled at the University of Breslau.

Yet she was clearly seeking answers, some of them (she later realised) of a

religious nature. Years later, Edith

recalled that between the ages of 13 and 21, she could not believe in the

existence of a personal God. Perhaps psychology, then emerging as a new science,

could provide the explanations she sought.

Edith was a

groupie to the Jewish intellectual crowd

Edith began attending lectures given by well-known psychologists, and prepared

seminar papers dealing with gestält psychology. Yet what she found disappointed

her. To Edith, psychology seemed fatally flawed because it failed to deal with

its fundamental premises in a clear and convincing way. Edmund Husserl’s book,

Logical Investigations, fell into her hands at precisely the moment when

she was searching for a better approach. Here at last seemed to be the clarity

of vision that Edith sought. Edith

decided to go to Göttingen and study with the “master” (as Husserl was fondly

called). Edith later wrote: “Something was pushing me to move on ... I

didn’t know anyone capable of advising me, so I blithely went about looking for

my own way myself.”

Göttingen at that time was the Berkeley

of Germany–a place where the currents of thought ran swiftest. Phenomenology

represented a new way of looking at philosophy, that sought to establish

once and for all the ultimate foundations of human consciousness and knowledge.

Edith soon got caught up in the enthusiasm. She quickly began attending

philosophy seminars, and is said to have been

Husserl’s most sensitive student.

She also developed friendships that sustained her for the rest of her life. An

especially important influence was Adolf Reinach, whom Husserl considered his

favourite interpreter. Reinach and his young wife, Anne (later to play a pivotal

role in Edith’s life) often entertained students in their home, and Edith was a

frequent visitor. Max Scheler, a Jewish convert to Catholicism, was an

intellectual dynamo who made quite an impact on Edith’s thought. His “prophetic”

view of phenomenology stressed the significance of emotion as a means to

discover human values, and was nearly as important as Husserl’s own system.

Göttingen at that time was the Berkeley

of Germany–a place where the currents of thought ran swiftest. Phenomenology

represented a new way of looking at philosophy, that sought to establish

once and for all the ultimate foundations of human consciousness and knowledge.

Edith soon got caught up in the enthusiasm. She quickly began attending

philosophy seminars, and is said to have been

Husserl’s most sensitive student.

She also developed friendships that sustained her for the rest of her life. An

especially important influence was Adolf Reinach, whom Husserl considered his

favourite interpreter. Reinach and his young wife, Anne (later to play a pivotal

role in Edith’s life) often entertained students in their home, and Edith was a

frequent visitor. Max Scheler, a Jewish convert to Catholicism, was an

intellectual dynamo who made quite an impact on Edith’s thought. His “prophetic”

view of phenomenology stressed the significance of emotion as a means to

discover human values, and was nearly as important as Husserl’s own system.

In addition to her academic studies,

Edith threw herself into the agitation for women’s equality, joining the

Prussian Association for Women’s Suffrage and the League for School Reform.

But the most powerful influence on her life was undoubtedly Hans Lipps. Hans was

a gifted medical student with a keen interest in philosophy. He and Edith became

nearly inseparable friends, exploring new ways of seeing the world. Whether

there was an actual romance is a matter of conjecture, but they certainly felt

deep affection for each other.

In addition to her academic studies,

Edith threw herself into the agitation for women’s equality, joining the

Prussian Association for Women’s Suffrage and the League for School Reform.

But the most powerful influence on her life was undoubtedly Hans Lipps. Hans was

a gifted medical student with a keen interest in philosophy. He and Edith became

nearly inseparable friends, exploring new ways of seeing the world. Whether

there was an actual romance is a matter of conjecture, but they certainly felt

deep affection for each other.

In many ways, Edith’s life at Göttingen was idyllic. Yet her world, like that of

millions of others, was soon to come crashing down. For nearly a century, Europe

had avoided a general war. But the intricate system of alliances that held

everything together was far more unstable than most people imagined. On

June 28, 1914, in a little-known place called Sarajevo, a fanatical

Serbian terrorist assassinated the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his

wife. Austria made impossible demands upon Serbia, and when they were not met,

declared war. Russia declared war on Austria. Germany declared war on Russia.

France declared war on Germany and Austria. Germany invaded Belgium, and England

declared war on Germany and Austria. The unthinkable had happened. Most of

Europe was at war.

|

|

|

CHAPTER I

COMMUNISM AND ITS IMPLOSION

IN EASTERN EUROPE

SERGHEI STOILOV GERDZHIKOV

INTRODUCTION

This paper aims to utilize elements of the phenomenological method, particularly the notion of the life-world (Lebenswelt), in order to begin an examination of communism and its explosive demise. Edmund Husserl introduced the notion of the life-world into phenomenological philosophy in The Crisis of European Sciences and Transcendental Phenomenology, defining it as the world of everyday life prior to any scientific knowledge of unquestionably clear things, i.e., as a world of "pre-predicative evidences" (Husserl 1977). Even though this world has a fully anonymous status, it is not immediately recognizable, and we are normally unaware that it exists as a particular world which has been defined and explained within a sociocultural context. For us, it is simply "the world".

Communism and the post-communist situation are not discussed here in terms of psychological, economic or politological description and explanation. Rather, an investigation is begun into how people have been living in the European countries of "real socialism," including the Soviet Union, Romania, Bulgaria, Yugoslavia, Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary.

A PHENOMENOLOGICAL APPROACH

The life-world is not some suspended network of meanings. Rather, it has its own space, time, logic and basic meanings, all of which are interconnected. Furthermore, it is extended through time, involving genesis, expansion and decline. These characteristics held true for the phenomenon of communism as well which, in its developed form, created a life-world of its own.

Communism developed in both European and non-European countries, and it was "immersed" deeply within the context of contemporary civilisation. However, the fact that it was highly isolated from the rest of the world is one of its intrinsic charac-teristics. In any case, the communist attitude, the communist idea and the communist phenomena of conscience and action constructed a separate social life-world having their own specific mentality, space and time. "Real socialism" was not simply the domination of one party, a planned economy and a totalitarian system, but was primarily an ethos, a mentality, a phenomenon. It did not disappear after having been rejected by its own institutions, but was then merely transformed into something else insofar as its power, like the power of all energy forms, can only be transformed and not destroyed. The basic meanings and notions that made communism a living reality still exist side by side along with the slowly advancing reform.

The attempt to comprehend communism constitutes a hope for orientation and control in the post-communist period. It is painful and perhaps impossible to change the former system upon the abstract basis of what a "normal" society and what its institutions should be when there is no understanding of the life-world. This problem is compounded when the result is that new institutions are merely transplanted, and thereby weakened, into the still living communist and socialist mentality. Without an understanding of the roots and the life forces that nurtured it, it is not possible to exit communism wisely.

But even if exiting from communism remains a spontaneous process not governed by wisdom, a comprehension of the phenomenon of communism will surely be useful in the face of any other projects that strive to engineer the human life-world. Today these include cloning, genetic control, artificial intelligence, biorobotics and various other tendencies to "rationally organize" life on the planet as a whole.

The phenomenology (more precisely, phenomenological sociology) of communism involves a clarification (Husserl’s Erklärung, Ideation) of meanings, something which cannot be done from an outsider’s position. In The Crisis, Husserl presents phenomenology as a philosophy that, contrary to both pre-scientific and scientific objectivism, goes back to knowing subjectivity as the location where all objective meanings and meaningful validities are formed. Its program is to undertake the task of understanding the world of existence as a mental formation of valid meanings (Husserl 1977). The most adequate paradigm for an "understanding" of the theory of communism is the phenomenological paradigm of the social as a living network of meanings that are intended and discovered by people. This way of comprehending communism (and post-communism) is acquired by people who have lived or still live in such a society. Phenomenological social knowledge is not speculation but rather experience as it has been thematized by means of phenomenological notions that describe the constitution of a great variety of events: life-world, phenomenon, meaning, significance, idea, attitude, vision, mentality, mental form and dynamics.

This type of social knowledge gives rise to a dynamic clarifica-tion of the phenomenon of communism in its development as a living entity of meanings and significances which does not rely upon exclusively causal explanations. While such clarification may be expressed through interpretations of texts and teleologically explained events and "rational actions" (Max Weber), it originates from the idea of the phenomenon as a living and full possession of the object of the intention (Husserl). Communism is precisely such an intended living entity and not an "objective fact" (communism as a non-implemented project remained only a vision within the main meaning). The scientific character of the phenomenological approach has today become widely recognized in the international scholarly community, one result being the development of new areas of research in phenomenological sociology and, in a broader sense, social knowledge as a whole. Prominent examples include the works of Alfred Schütz (constitutive phenomenology of the natural disposition), the ethnomethodology of Harold Garfinkle and the research of the contemporary phenomenologist Richard Gratchoff. Instead of working with "objective notions," this sociology rather utilizes "types" similar to the "Ideal Types" of Max Weber (Weber 1960).

People recognize, understand, and act towards things and events in the life-world with ready norms of significance, and they do not have unique requirements for every fact or event. For the people living in the world of "real socialism," things such as "money," "power" and "dignity" and events like "revolution," "queue" or "shady deal" meant something familiar and specific that was nevertheless unknown to people outside the system. These names contained codes for understanding and action that were valid only for real socialist life, comprising a set of meanings that existed only in a common intersubjective life-world (Husserl 1977; Schütz 1981).

In addition, life is not only a quality but also a form of the life-world and its phenomena. Through its form, life is an organic unity of components and processes that reproduces itself in conditions of spontaneous disintegration and chaos. Life is the reproduction and expansion of order in chaos; it is always a motion towards life, an order and escape from non-life, from chaos. That which is alive is born, grows against entropy and finally dies, disintegrating into chaos. Moreover, every form of life, every biological species or social formation, has its own unique identity that it projects in a unique form (order) of its life-world. Human space, time and logic are specifically human, different from the space, time and logic of the other forms of life.

Communism is a human social form, i.e., it is a concretization of human form in its sociality. The human world in this particular social form is a characteristically human intersubjective world.

LIFE PROJECT AND WORLD PROJECT

What meaning is to be ascribed to the "phenomenon of communism"? This is ultimately the broadest set of mental forms that have given life to the texts, actions and events concerned with the argumentation, planning and realization of communism. This set is both varied and homogeneous, much in the same way as Wittgenstein’s multitude of "family resemblance" forms. I will endeavor to consider those which are most strongly represented and can be idealized as "pure types."

Communism is understandable as a phenomenon of Western civilization that is alien to the mentality and practices of the Middle and the Far East. In addition, certain writers, primarily such Russian historians and philosophers as Geller-Nekritch or Nikolai Berdiaev, have been tempted to describe communism, Bolshevism in particular, as a Russian phenomenon. But while Bolshevism is an historic fact, it does not necessarily carry an understanding of the mental form of communism as a project. In any case, there should be no mixing of the rationalistic phenomena of Western engineering with traditional Eastern societies (Weber), among which Russia is included to some significant degree.

The present investigation into the phenomenon of communism begins with a genetic statement, namely, communism is rooted in the archetype of logos. The vision of the world as a logos, i.e, an objective order that can be presented in words and figures, also contains the vision of the world as an object of technology. The latter involves the demiurgic vision of a "better world" different from ours that can be created by human beings through the use of the world’s laws, its logos.

But communism reached a deadlock and collapsed before it fulfilled its declared design. Furthermore, the effort to realize the communist project brought about huge destruction. Why did communism not succeed? Would it be possible for another such project to survive? Against the background of such questions, the major supporting thesis of the present discussion is that this type of project is doomed to failure because the demiurgic vision of "world creation" is false. The world (the human life-world) cannot be exhaustively grasped and expressed as logos and it is not the object of technology. Realities such as "freedom," "man" and "justice" that are compatible with the human life-world are not technological in nature. Life is not an artifact.

Plato’s state was moral, perfect and ideal, representing a sensible projection of the idea of justice that exists in a better world, the world of ideas (Plato 1984). Society was to be organized in a holon where each person and action would find its own functional place. Charles Fourier proclaimed that the "human breeding" that was to take place there would be in harmony with the idea of justice, thanks to the radical acquirement of human reason and the discovery of the "four phases of history" (Fourier 1953). Now, for Karl Marx as well, the world must not simply be explained, it must be changed (Marx 1978b). Moreover, communism was to be a "real human history" that would replace the current "pre-history" (Marx 1953a) in that people would come to create their own history in compliance with the laws of history. In doing so, they were to make the "jump from the kingdom of necessity to the kingdom of freedom" (Marx 1953b).

Communist ideology, rather radically expressed in Manifesto of the Communist Party, envisioned a total revolution in which basic values of Western civilization were rejected as class-determined" values and new ones approved, including a new status for the "person" after the "bourgeois person" had been eliminated. The Manifesto puts forward the project of a communist revolution that is to be implemented by means of the expropriation of property and the replacement of the parliamentary order with dictatorship. Revolutionaries in Lenin’s party as well as communists in the rest of the world implemented precisely that project when they carried out their designs for a "new world," a "new life" and a "new man."

Communism was a grand experiment of Western reason that was born from the ancient understanding of the world as "logos" and "idea." According to this view, the world is ordered in a certain manner (logos) and is permeated with laws that are knowable and expressible in words and figures (logos). Furthermore, reality can be changed on the basis of this notion (techné). Consequently, the world is grasped not as a boundless and undefined reality, but rather as a transparent and technological sphere. In the West, only that which is initially logical and profoundly transparent is taken to be reality. To this is added the Western belief, inherited from the Renaissance although somewhat weakened today, that reason is able to construct our world.

However, this view eliminates the difference between a living creature and a non-living artifact. It also renders invisible the human form standing at the basis of the creation of artifacts that would seem to indicate the limit of technology. Logos does not recognize the boundary between the world and man. When logos is made the universal principle of order, all differences and oppositions are eliminated between knowledge and the hidden, the knowable and the unknowable, the attainable and the unattainable. If the Universe is ordered by means of logos, then it is entirely achievable in and through logos, i.e., in and through speech, science and action. Consequently, the world can be designed, or at least reconstructed and changed. This is the general mental form of "demiurgic intention."

When the world apparently escapes explanation and control, a demiurgic adjustment that endeavors to design a world project is solicited. Life is not just; people are not equal. The recognition of this reality gave rise to a grandiose, demiurgic attempt by Western man to take control of life and the world in concordance with the logos archetype. Such is the general mental form of the Utopian project in Western civilization. The term "rationalistic Utopia" is widespread, and where else if not in the West is rationalism the quality of an entire civilization? Now, Max Weber differentiates between, on the one hand, Western rationalistic society and "rationalistic control," and, on the other, Eastern and pre-modern "traditional" and "charismatic" society and control (Weber 1970). A demiurgic project is impossible in the East, where the world as definable in words is empty and unstable, and the unborn and the undisappearing absolute is beyond logic and inaccessible to language, outside of logos (Suzuki). Such a world cannot be subject to technology, at least not in the Western sense.

The ancient Western world prior to the emergence of the logos archetype was not demiurgic, nor is the modern Western world that has been developed by means of contemporary liberal democracy. Neither of them is the fruit of some global plan for world restructuring. On the contrary, both have been based upon the recognition of the inalienable human rights of life, freedom, dignity and property within an accepted world (Locke 1965). Parliaments, separation of powers, private property and its legal guarantees, ship transport and science itself — all of these have emerged through an accumulation of human ideas, practices and attainments within the context of acknowledging human reality as being in itself a value in the Christian spirit. All of these achievements have appeared without a general scheme, like an unfocused net of local projects and spontaneous creative acts (Hayek 1952).

In contrast to this spontaneous order, which August Hayek called an extended order, communism has sought to produce a planned and thoroughly controlled order in accordance with an all-encompassing theory and scenario of epochal proportions. This has been the case in all the countries where communism became dominant without exception. This type of order corresponds to the vision that Marx and Engels outlined in such works as "Theses on Feuerbach", The German Ideology, the Manifesto, "Critique of the Gotha Program," "The Development of Socialism from Utopia to Science," Feuerbach and the End of German Classic Philosophy and Anti-Düring. The Lenin doctrine on revolution and proletarian dictatorship as presented in State and Revolution comprises a power monopoly project that is consistent with this view in all important respects.

But what shall we say about "capitalism"? Is it too not a logos project? Does it not design a world? Although Western capitalism is rational as a state and as an economic process (Weber), this rationality concerns only institutions and not control over social life (Hayek). Capitalism and liberal democracy comprise techonolgies for controlling non-living structures, such as state institutions, laws and market rules, not technologies for controlling life. No one within the tradition of liberal democracy has yet intended to construct some grand vision of a social system of life through utilizing the forces of society as a whole. What has instead been done is to establish a legal order that rests upon the idea of human rights.

Western scholars of totalitarianism have drawn, albeit not very clearly, this important distinction between liberal democracy and communism. For them, totalitarianism is a form of utopian engineering that differs from more gradual types of social engineering only by its restriction of criticism and its scale, not by its attitude to life (Popper 1962; Fukuyama 1992). The communist project may thus be regarded entirely rationally and critically, just as may be done with any other human project. It is, although borderline, a mental and active experiment that aims at radically changing the world. If it would succeed in creating a new world, a new human life and, moreover, a new human form at a higher level of life ("happiness, welfare, freedom"), then it would be false to maintain that the world and the human forms which correlate with it are unattainable. If, on the other hand, it would lead to the destruction of a human or world form, then it would be false, weak and lifeless. In the latter case, chaos would conquer a new space within peoples’ life.

Any rational project orients and fixes the spontaneous movements of life towards wholeness and expansion. But if it is possible to create cities and states, cannons and machines, theories and poems, philosophy and religion, then why should it be impossible to create a whole new world for human beings? What is impermissible here?

It is one thing to build cities or write poems, but it is an entirely different thing to breathe, laugh and feel pain and enjoyment, i.e., to live spontaneously. Can we design our life the way we design artifacts? Since each creation is a definition in itself, it is a distinction within a living context that itself remains undefined. If and when we seek to define the "world as a whole," does this mean that we are capable of rationally enveloping and controlling it?

No. The latter effort would comprise both an intention and a practice that are inconsistent with the form of life itself. When people intend to create a new society and a new human being, they set themselves a task that cannot be completed because it "transcends" the limits of human form and thereby falls into absolute impossibility. Such an effort wrongfully renders life as an object of technology and design, and mistakenly identifies life as an artifact.

The fundamental distinction from the perspective of the present examination between a "world project" and ordinary human actions is that the linguistic structure of the former is ontologically inconsistent. Life is a forward movement of living form against chaos and towards re-synthesis; life "emerges" from the ocean of chaos by means of its own activity. The world is precisely this and nothing more. (This situation is analogous to the structure against entropy of open systems in physics). Life is a movement of the preservation and expansion of life, and it possesses a teleological form (the form of entelechia). Life is vigorous only so long as it succeeds in compensating for its spontaneous disintegration and in creating a redefined form for itself.

Human beings neither choose nor deliberately design human form, nor do they design the life-world in the way they design their machines. Neither human form nor the life-world is subject to technology. On the contrary, the life-world is discovered by the human being who has been born into the world, who has already become shaped into a human and cultural form. A human being first preserves the world s/he has found, then expands it, and finally loses it in death. Human consciousness is one moment of human life, and it moves in the same direction as that life, continually re-synthesizing itself against its own loss. A human being cannot make human form subject to one or another distant realization and objectivation. If one were to do this, one would somehow have to step outside of human form, come to know it and then exercise one’s influence upon it. But this would mean to step out of the only world that belongs to a human being as such, namely, the human life-world. The human life-world thus permits all human actions, but none of these actions, insofar as they possess a human form, refer to some "transcendent" intention and practice whereby human form as such could be deliberately altered. When human beings design machines, write poems and create science and religion, they do not change human form, but rather only project it and expand the horizons of the life-world.

EXPLOSION AND STORM

Not only is building a world a project that is ontologically problematic, it is a type of nonsense similar to that of trying to create a perpetuum mobile. The world has a human form insofar as it is a projection of human form. This transcendental perspective shows us that every attempt to create a life-world can actually be reduced to the creation of something within this world that does not change the form of the latter. Moreover, such an attempt is in fact destructive because of its disintegrative affect upon certain basic structures of our living social body. We can never create the world, just as we can never create the human form. Every act of creation is rather a dynamic within this form.

The outcome of communism in Eastern Europe and its deep crisis outside of Europe (except in China, where a communist economy no longer exists) together comprise the implosion of a world that human beings sought to build according to a demiurgic plan. There has hardly been a more drastic change in Western history than the change to post-communism, and even today no one knows how it will turn out. None of the post-communist countries has reached a state of equilibrium that can be compared with the equilibrium of Western democracies, nor is it clear whether any future equilibrium might correspond to the criteria of modern society. Indeed, it might very well be the case that post-communism is a type of chronic disease that will never lead to equilibrium. The best possible scenario is that any future equilibrium that may emerge will bear deep traces of communism.

The post-communist storm has resulted from the powerful gradients for imbalance that existed within communism. An unsound system was destroyed because of the destructive tensions within it. But precisely what tensions did the catastrophic end of communist release? What forces has the catastrophe set free, what kind of genie has been let out of the bottle? Perhaps more importantly, what tensions have been created by the subsequent partial stabilization? Any attempt to predict what might happen demands a deep insight into communism, but only time is capable of giving us answers. The fact is that economic, political and cultural meanings and texts are now rapidly changing. However, any false stability that may be attained can be forcibly maintained only for so long before it will implode, unleashing more violent forces. Such a dynamic state is so uncertain that it can only be defined as a shock.

What will the consequences be of this shock? Will a normal market economy, normal democracy and a sound mind emerge in the foreseeable future? The deformations into which communist forms have been transformed comprise the cost of any future equilibrium, but it is still not yet clear precisely what they are. And if this equilibrium will itself be fraught with anomalies and the sources of new disequilibrium, what will these be?

The "ship of democracy" is sailing in the storm of post-communism. Reform is carried out as a series of actions by state power in order to create a system of market economy and democracy. What chances does the ship stand? How do the existing "unhealthy" tensions effect the attainment of the goals of reform? Perhaps the waves of the storm displace forces and meanings in a way that is essentially independent of the goals of government and essentially anomalous in a "normal" state. Unfortunately, such anomalies may be chronic in the absence of forces capable of neutralizing them in the foreseeable future.

Post-communism thus appears to be a period of intensive recovery complicated with vestiges of communist anomalies and forces for destabilzation, the effects of which are unique and unprecedented in history. Post-communism is indeed unique. Never before has there been such a phenomenon and there is no theory that adequately describes it. No one knows where post-communist transitions are leading, just as no one knows what the effects of a series of earthquakes will be. In this regard, our understanding of post-communism is in phase with its movement.

Post-communism is essentially chaotic and undefined. It is analogous to the "dissipative" structures and processes that lead to "metastable states" in Prigogine’s sense. Such a dissipative process is one effect of an explosion B, the explosion of highly tensioned communist totalitarian society. The result is some future metastable state B at some unknown distance from thermodynamic equilibrium, from absolute chaos. There are forces and flows in this dynamic — forces of wealth, power and mentality, and flows of money, political actions and social thinking. In this non-equilibrium, the positive forces of the reform, i.e., the actions of the government, are in contraphase with the negative forces of free fall, illegal money making, unhealthy and inadequate policy, and the conservative mentality of a closed society. In such a period, certain new forms of mentality, power and wealth arise that can be understood only as a network of rational actions (Weber).

Philosophy Faculty

Sofia University

Given that so many on the far-left are considers saintly (Dorothy Day and Bishop Oscar Romero) and some were even made saints (Edith Stein - she thought the Soviet hammer & sickle and the Cross could be reconciled. In an Orthodox-Catholic discussion group I wondered allowed if anyone who thought the Nazi swastika and Cross could be reconciled would be made a saint by the Catholic Church. The observation was unanimously dismissed as absurd.) what in the world makes you think that the Catholic Church would publicly denounce a leftist political party?

I would also like to add that I think that what Edith Stein did on behalf of the poor and Jews in WWII France was very noble and brave. I also think that Dorothy Day did great work on behalf of the poor, and Bishop Oscar Romera was a strong and brave, if niave, proponent for the poor and oppressed people in El Salvadore.

All of that, however, doesn’t diminish the following: Edith Stein was an earlier participant in the Russian revolution and did try to reconcile the Communism and Christianity. Dorothy Day worked daily on behalf of what she called “economic communism”. Bishop Romero, naively one may argue, gave aid and comfort to a Communist backed insurgency that doomed the poor he cared so much about as much as the fuedal economic system he so often preached against.

Submit corrections and additions to Marianne Sawicki at sawicki@morgan.edu

Copyright © 1998-2000 Marianne Sawicki.

![]()

Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross

http://www.carmelites.ie/Archive/johnpaul1oct1999.htm

Letter from Pope John Paul II Proclaiming Teresa Benedicta of the Cross Co-Patroness of Europe

Spanish-speaking Catholic asks about Gertrude Stein

movie

http://llwyd.tripod.com/nuns/stein.htm

movie

http://llwyd.tripod.com/nuns/stein.htm

Cologne

on 15 October 1933, she took the veil

on Sunday, 15 April 1934.

Cologne

on 15 October 1933, she took the veil

on Sunday, 15 April 1934.

http://www.carmelites.ie/Archive/johnpaul1oct1999.htm

Letter from Pope John Paul II Proclaiming Teresa Benedicta of the Cross Co-Patroness of Europe

Spanish-speaking Catholic asks about Gertrude Stein

<center>

[img]Babi_Y14.jpg[/img]</center>

Mathias, or any holocaust debater, can't really argue because the subject

is absurd. [url=Babi_Yar.htm]Babi Yar[/url] had

200,000 Jews shot at a ravine in the city limits of Kiev. The main witness

is a crazy Jewess puppeteer called Nina Proviechi.

No one with a brain would touch these stories. The Holocaust museum's new

approach is to talk about other genocides in Africa, or where ever

** ON EDITH STEIN

By Vincent Reynouard

(from ANEC INFORMATIONS, c/o B.P. 256, B-1050 BRUSSELS-5, BELGIUM , 29 October 1998, pp.3-5)

(translated by Carlos W. Porter; the quotations from the Nuremberg Trial transcript are retranslations which do not accord with the official translation or pagination in the English-language IMT volumes)

The canonization of the Carmelite Edit Stein by Pope John-Paul II has resulted in abundant mail. Our readers are wondering about the reasons why the nun was deported and the exact circumstances of her death. To answer these questions, ANEC is publishing the following.

E. Stein was born in 1891 at Breslau in a Jewish family. Although educated in the Jewish religion, she became an atheist and remained so until the age of 21. In 1921 she was converted, particularly, as the result of reading a book describing the life of Saint Teresa. Her baptism took place on 1 January 1922. From 1923 to 1931, she lived in the monastery of Saint Madelaine of the teaching Dominicans. There she taught upper levels of German.

Converted to liberal ideals at a very early age, she had, in her youth, defended women's rights and supported the right to strike. After 1918, she became committed to the democratic party, speaking at a meeting on the occasion and defending the Weimar republic.

Opposed to National Socialism, "she encouraged her students to form a group opposed to the Nazi student group - ANST - and took part in meetings with representatives of both sides taking part." [See: Comme l'or purifie par le feu. Edith Stein, 1891-1942, editions Plon, 1984, first editions au Seuil, 1954, p. 126. All the information published in this article was taken from this work.] After Hitler's accession to power, the authorities pressured the Catholic institute which employed Edith Stein to make her stop teaching. E. Stein therefore received a notice to give up teaching (at least for a time) and dedicated herself exclusively to her research work ["The president] added that he believed it preferable that I give up teaching my summer courses to dedicate myself exclusively to my research work", [excerpt from notes left by E. Stein, Comme l'or… p. 133].

In October 1933, she chose to take a vow which had been dear to her for ten years: to enter the Carmelite order. She received the habit on 15 April 1934 and pronounced her perpetual vows six days later. Although withdrawn from the world, she pursued, within the Carmelites, her action in opposition to National Socialism. On 10 April 1938, for example, she read a prebscite organized by the central authorities. The Carmelites having decided, by a majority, to abstain, E. Stein (having become Sister Benedicte), "usually so sweet and submissive, vehemently objected to such an idea" (op cit p. 185).

"She adjured her sisters to vote against Hitler, whatever the consequences of such an attitude for the Community and to each one of them. She represented to them that Hitler was the enemy of God and would drag Germany with him into an abyss of evil. She spoke with ardour, almost violence, forgetting all reserve" [ibid].

During a preceding plebiscite, as E. Stein had not gone to vote, two men had come to Carmel and had offered to drive her to the city so that she might fulfil her civic duty. She had ostensibly answered: "if these men attach such value to my 'no', I cannot refuse it to them" [ibid, p. 184].

After the Christmas festivities of 1938, E. Stein fled Germany and moved to the Carmelites of Echt, in the Netherlands. Two years later, nevertheless, this country was also occupied by the Reich. In 1942, the nun resolved to request a visa for Switzerland. It is probable that this request aroused the attention of the police; in the following weeks, E. Stein was interrogated twice by the Gestapo: at Maastricht and at Amsterdam.

Then suddenly, on 2 August 1942, while the negotiations continued with the authorities to obtain a visa, she was arrested and taken away by the Gestapo along with 300 non-Aryan priests and nuns [ibid, pp. 206-207].

According to some sources, these arrests constituted a reprisal measure in response to a pastoral letter denouncing the persecution of the Jews, a letter which had been read in its entirety in the majority of Catholic parishes of the Netherlands (while the occupying authority had demanded the excision of one passage) [See: Comme l'or… pp. 204 et seq. "The same day [as the arrest of E. Stein], in the evening, the adjutant commissioner Schmidt announced in an official speech, that this was a reprisal measure in response to the protest on the part of the Dutch bishops".]

At Nuremberg, however, the former commissioner of the Reich for the Netherlands, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, provided another version. He declared that starting in 1942, Heydrich, who had been invested by Hitler with unlimited powers, had ordered the evacuation of the Dutch Jews [See IMT, pp. 690-91, retranslated from French volumes: "This must have happened in 1942, I believe, when Heydrich formulated new requirements relating to the evacuation of the Jews (…) Heydrich showed me a Hitler order, according to the terms of which he was invested with unlimited powers for the execution of all measures in the occupied territories. I asked through Bormann what that meant, and this order was then confirmed to me. The evacuation of the Jews began on this basis".]

Heydrich was certainly acting in the framework of a "final territorial solution" of "the Jewish question decided in 1941; another reason also advanced for this evacuation was that, sooner or later, Holland would become a theatre of operations and that one could not then permit a hostile population [ibid, p. 690, French text, retranslation). Although opposed to such a measure, Seyss-Inquart had to obey.

As a result, the arrest and deportation of E. Stein seems rather to form part of a general plan of evacuation than part of a measure of reprisal as the result of a pastoral letter. But it is possible that these two causes co-existed, since they are in no way mutually exclusive.

E. Stein was first of all taken to the Westerborg camp (in northern Holland), which had been set up to gather the Jews scheduled for deportation. At Nuremberg, A. Seyss-Inquart declared without contradiction:

"In the same camp, there was a service of order made up of Jews. The camp was separated from the outside world by the Dutch police; there was simply a Police security command to supervise the interior of the camp. In the totality of the files, I did not note any report on abuses committed in the camp itself. Each Sunday, priests came to the camp; in any case, one priest for the Jews of catholic religion, and another for Jews called Christians, and they didn't make any report either" (IMT XV 682, retranslation).

E. Stein was finally deported (at the same time as her sister) to Auschwitz in the night of 6-7 August 1942. Is there any proof that she was murdered upon her arrival at the camp? No. On 16 February 1950, the Official Journal of Holland published lists of persons having died during deportation. Under nos. 44,074 and 44,075, it reads:

Edith-Teresa-Hedwige STEIN

Born 12 October 1891, at Breslau

Deported from Echt + (died) 9 August 1943.

Rose-Marie-Agnes-Adelaide STEIN

Born 13 December 1883, Lublinitz

Deported from Echt + (died) 9 August 1942.

In response to inquiry, the Dutch Red Cross answered that the date of 1943 was erroneous, that it was a misprint, and that "both sisters actually must have died in the gas chamber at Auschwitz, on 9 August 1942" (see Comme l'or… p. 218). Note the conditional turn of phrase. In reality, the date of 9 August 1942 corresponded to the arrival of the Stein sisters at Auschwitz; in fact, the date of their deaths is an unfounded extrapolation. As to the claim that they died in the "gas chamber" (singular) "at Auschwitz" is a serious untruth, since, in view of the studies of Robert Faurisson, later taken up by Fred Leuchter and Germar Rudolf, we know that there was never a homicidal gas chamber at Auschwitz.

Let us moreover stress that, until 1947, some people believed it possible that E. Stein might return; they based their hopes on "information from former inmates or deported persons" (ibid, p. 218). The fact that she did not return does not detract from the truthfulness of these persons, since she arrived at Auschwitz in the midst of a typhus epidemic (which was already four months old) [On the typhus epidemic at Auschwitz in August 1942, see Robert Faurisson, Memoire en Defense, La Vieille Taupe, 1980, p. 15].

It is also possible that the nun [Stein] only transited Auschwitz to be then sent to another camp. Such transfers were not unusual: we know, for example, that, on 19 August 1944, one thousand Hungarian Jewish women left Auschwitz for Allendorf-lez-Kirchhain, a commando of women administratively dependent upon the Buchenwald camp [See the Catalogue alphabetique des camps de concentration et de travaux forces [published by the Belgian Ministry of Public Health in 1951, p. 5.]

Now, according to the official history, these women should have been gassed immediately upon their arrival at Auschwitz. On 9 August 1942, one thousand Jews from Auschwitz III arrived at Gross-Rosen (ibid, p. 152). Upon the liberation of the camps, deported Jews, such as E. Stein, deported from Westerborg, were found not only at Auschwitz (ibid, p. 142), but also elsewhere (for example, a commando administratively dependent upon the Gross-Rosen camp, ibid, p. 177).

Consequently, there is no proof that E. Stein died at Auschwitz, whether murdered or not.

Conclusion

Jewish by birth, converted to Catholicism, and having become a Carmelite, opposed to National Socialism, E. Stein finally died following deportation. Her canonization by John-Paul II in 1998 was the occasion of numerous lies. The most serious of them consisted of claiming that the nun had been gassed upon her arrival at Auschwitz, in the context of the genocide of the Jews planned by the "nazis". Now, even if one has no knowledge of the work of the revisionists, honesty demands a statement that we know nothing of the place, the causes, or circumstances of her death.

But it is true that for the peddlers of the Shoah, these "details" are of little importance. E. Stein died following deportation, they say; therefore, she was murdered. Such a state of affairs is not surprising; the official history of the concentration camp system is only an accumulation of untruths and hazardous hypotheses skilfully, or haphazardly, patched together.

It is nevertheless unfortunate that someone who claims to be the Pope has made himself the accomplice of the ambient lie, above all when the lie is utilized by some people to destroy the Catholic Church.

VINCENT REYNOUARD

ANEC Informations 29 October 1998

|

France:

History Teacher Jailed for

Thought Crime Report; Posted on: 2004-06-13 02:07:46 [ Printer friendly / Instant flyer ] |

||

|

A TEACHER banned from working in France for peddling revisionist views on the Holocaust has been sentenced to two years in prison by a French court after he made a film contesting a brutal Second World War massacre by Nazi SS storm-troopers.

The conviction of Vincent Reynouard, 33, coincides with the 60th anniversary today of the slaughter of 642 villagers, including 245 women and 207 children, at Oradour-sur-Glane on 10 June, 1944, four days after the D-Day landings by Allied forces.

In his film entitled The Tragedy of Oradour-sur-Glane: 50 Years of Official Lies, Reynouard blamed the inhabitants of the tiny Limousin village for their fate.

Disputing evidence of eyewitness survivors, the former teacher denied that the SS deliberately killed more than 350 women and children after rounding them up and ordering them into the village church, arguing that the deaths were due to explosives concealed in the church by members of the French Resistance active in Oradour.

Reynouard had sent videos of his film, along with order forms for additional copies, to the last two living survivors of the massacre, the village memorial centre (now a national war memorial and museum) and to the mayor of Oradour and numerous villagers.

Reynouard was first convicted in 1991 of distributing revisionist literature when he was a student in Caen, in Normandy. Six years later he was sacked from his post as a maths teacher at a technical college in nearby Honfleur, after he set homework involving counting Dachau concentration-camp victims and was discovered to have stored revisionist documents denying the Holocaust on the school computer.

Reynouard was eventually banned from teaching anywhere in France. He also wrote a revisionist book questioning the Nazi slaughter entitled The Oradour Massacre: A Half-Century of Theatre.

In 1998, some 500 French and German copies of the book were seized by police in Brussels and the Flemish port city of Antwerp at the request of French judicial authorities.

Reynouard’s sentence was handed down by the Limoges appeals court, which said that his film had insulted the memory of those who had been massacred.

The court doubled his original prison sentence, but reduced his fine of 10,000 (£6,688), ordering him instead to pay 1,000 (£668) in damages to each of the three civil parties in the case, including Marcel Darthout, one of the last two survivors of the massacre still alive today.

Today, only the stone skeleton of the original Oradour-sur-Glane remains. The late president Charles de Gaulle ordered that the charred ruins of the village should be left as a memorial to the suffering of France under the Nazi occupation and a new village was constructed nearby.

A rusting bicycle, a blackened iron bedstead and the charred wreckage of a baby carriage are still standing as a chilling reminder of the horrific events of that spring afternoon when Hitler’s troops razed the village to the ground and murdered its inhabitants.

The massacre is believed to have been a reprisal for a French Resistance attack which killed 40 Germans following the D-Day invasion.

The SS Das Reich storm-troopers were heading for Normandy when they were ordered to attack the village, a sleepy backwater near Limoges with little Resistance activity. Many historians have argued that the Nazis attacked Oradour-sur-Glane in error after mistaking it for nearby Oradour-sur-Vayres, a suspected Resistance stronghold about 15 miles away.

On their arrival, the SS rounded up children and women, many carrying babies in their arms, and marched them to the village church, where they locked them inside before throwing in grenades filled with poison gas, and opening fire.

As those who survived screamed for mercy, the SS built a human bonfire by throwing wood on to their badly injured bodies and setting it alight. Only one woman escaped from the church, by throwing herself from a 12ft-high altar window.

Among the 60 troops who perpetrated the massacre were 14 French nationals from the eastern region of Alsace, of whom all but one had been conscripted by force.

Related topic