|

Radiofrequency Radiation

|

|

Radiofrequency Radiation

|

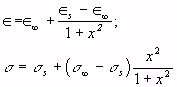

) and conductivity (

) and conductivity ( ).

Both properties change with temperature and, strongly, with

frequency. As a matter of fact, as the frequency increases

from a few hertz to gigahertz, the dielectric constant

decreases from several million to only a few units;

concurrently, the conductivity increases from a few millimhos

per centimeter to nearly a thousand.

).

Both properties change with temperature and, strongly, with

frequency. As a matter of fact, as the frequency increases

from a few hertz to gigahertz, the dielectric constant

decreases from several million to only a few units;

concurrently, the conductivity increases from a few millimhos

per centimeter to nearly a thousand.

,

,  , and

, and  --of the dielectric constant at low,

medium, and very high frequencies. In its simplest form each

of these relaxation regions is characterized by equations of

the Debye type as follows,

--of the dielectric constant at low,

medium, and very high frequencies. In its simplest form each

of these relaxation regions is characterized by equations of

the Debye type as follows,

,

,  , and

, and  dispersions. They include for the

dispersions. They include for the  -effect, apparent membrane property changes as described in the text; for the

-effect, apparent membrane property changes as described in the text; for the  -effect, tissue structure (Maxwell-Wagner effect); and for the

-effect, tissue structure (Maxwell-Wagner effect); and for the  -effect, polarity of the water molecule (Debye effect). Fine structural effects are responsible for deviations as indicated by the dashed lines. These include contributions from subcellular organelles, proteins, and counterion relation effects.

-effect, polarity of the water molecule (Debye effect). Fine structural effects are responsible for deviations as indicated by the dashed lines. These include contributions from subcellular organelles, proteins, and counterion relation effects. (Equation 4.1)

(Equation 4.1) -dispersion

effect. Rotation of molecules having a permanent dipole

moment, such as water and proteins, is responsible for the

-dispersion

effect. Rotation of molecules having a permanent dipole

moment, such as water and proteins, is responsible for the

-dispersion (water) and a small addition to the tail of the

-dispersion (water) and a small addition to the tail of the

-dispersion. The plot does not include the

-dispersion. The plot does not include the  -dispersion.

-dispersion. -dispersion is due solely to water and its

relaxational behavior near about 20 GHz. A minor additional

relaxation (

-dispersion is due solely to water and its

relaxational behavior near about 20 GHz. A minor additional

relaxation (  -dispersion is caused in part

by rotation of amino acids, partial rotation of charged side

groups of proteins, and relaxation of protein-bound water

which occurs somewhere between 300 and 2000 MHz.

-dispersion is caused in part

by rotation of amino acids, partial rotation of charged side

groups of proteins, and relaxation of protein-bound water

which occurs somewhere between 300 and 2000 MHz.

-dispersion is presently the least clarified.

Intracellular structures, such as the tubular apparatus in

muscle cells, that connect with the outer cell membranes

could be responsible in tissues that contain such cell

structures. Relaxation of counterions about the charged

cellular surface is another mechanism we suggest. Last but

not least, relaxational behavior of membranes per se, such as

reported for the giant squid axon membrane, can account for

the

-dispersion is presently the least clarified.

Intracellular structures, such as the tubular apparatus in

muscle cells, that connect with the outer cell membranes

could be responsible in tissues that contain such cell

structures. Relaxation of counterions about the charged

cellular surface is another mechanism we suggest. Last but

not least, relaxational behavior of membranes per se, such as

reported for the giant squid axon membrane, can account for

the  -dispersion (Takashima and Schwan, 1974). The relative

contribution of the various mechanisms varies, no doubt, from

one case to another and needs further elaboration.

-dispersion (Takashima and Schwan, 1974). The relative

contribution of the various mechanisms varies, no doubt, from

one case to another and needs further elaboration.

,

,  , and

, and  -dispersion centered at about 2 kHz, while

muscle displays a very strong one near 0.1 kHz. The

-dispersion centered at about 2 kHz, while

muscle displays a very strong one near 0.1 kHz. The

- and

- and  -dispersion, however, is always sharply defined at the same

frequency range.

-dispersion, however, is always sharply defined at the same

frequency range.

-,

-,  -Dispersion Effects

-Dispersion Effects -dispersion characteristic of water. To the water's

-dispersion characteristic of water. To the water's

-dispersion, biological macromolecules add a

-dispersion, biological macromolecules add a  -range

as indicated. Suspensions of cells free of protein would

display a Maxwell-Wagner

-range

as indicated. Suspensions of cells free of protein would

display a Maxwell-Wagner  -dispersion of water. If the cells contain protein an additional,

comparatively weak

-dispersion of water. If the cells contain protein an additional,

comparatively weak  -mechanism due to counterion relaxation is

added; and if their membranes relax on their own as some excitable membranes

do, an additional mechanism may appear.

-mechanism due to counterion relaxation is

added; and if their membranes relax on their own as some excitable membranes

do, an additional mechanism may appear.

s term

in Equation 4.1 due to the ionic conductance of the dissolved

ion species. The static dielectric permittivity of

electrolytes of usual physiological strength (0.15 N) is

about two units lower than that of pure water (Hasted, 1963),

a negligible change.

s term

in Equation 4.1 due to the ionic conductance of the dissolved

ion species. The static dielectric permittivity of

electrolytes of usual physiological strength (0.15 N) is

about two units lower than that of pure water (Hasted, 1963),

a negligible change.

s, observed at f << fc = 20 GHz

s, observed at f << fc = 20 GHz

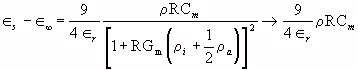

(Equation 4.2)

(Equation 4.2)

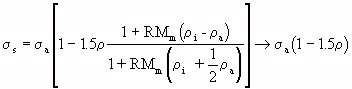

(Equation 4.3)

(Equation 4.3)

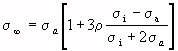

(Equation 4.4)

(Equation 4.4)

for the limit values of the simple dispersion that characterizes the frequency dependence. The time constant is

(Equation 4.5)

(Equation 4.5)

In these equations, Cm and G m are capacitance and

conductance per square centimeter of the cell membrane; R is

the cell radius; ![]() is the cellular volume fraction, and

is the cellular volume fraction, and ![]() i =

1/

i =

1/![]() i and

i and ![]() a = l/

a = l/![]() a are the conductivities of the cell

interior and suspending medium. The equations apply for

small-volume fractions,

a are the conductivities of the cell

interior and suspending medium. The equations apply for

small-volume fractions, ![]() , and assume that the radius of the

cell is very large compared with the membrane thickness. More

elaborate closed-form expressions have been developed for

cases when these assumptions are no longer valid (Schwan and

Morowitz, 1962; Schwan et al., 1970), and an exact

representation of the suspension dielectric properties as a

sum of two dispersions is available (Pauly and Schwan, 1959).

If, as is usually the case, the membrane conductance is

sufficiently low, Equations 4.2-4.5 reduce to the simple

forms to the right of the arrows.

, and assume that the radius of the

cell is very large compared with the membrane thickness. More

elaborate closed-form expressions have been developed for

cases when these assumptions are no longer valid (Schwan and

Morowitz, 1962; Schwan et al., 1970), and an exact

representation of the suspension dielectric properties as a

sum of two dispersions is available (Pauly and Schwan, 1959).

If, as is usually the case, the membrane conductance is

sufficiently low, Equations 4.2-4.5 reduce to the simple

forms to the right of the arrows.

, which determines the frequency where the impedances 1/

, which determines the frequency where the impedances 1/ CmR and (

CmR and ( s -

s -

, is exceptionally high.

, is exceptionally high.

s,

s,

,

,

s -

s -

), and

), and  , the three quantities Cm,

, the three quantities Cm,  Cm, is about 0.5

Cm, is about 0.5 Go to Chapter 4.1.2

Return to Table of Contents.

Last modified: June 24, 1997

© October 1986, USAF School of Aerospace Medicine, Aerospace Medical Division (AFSC), Brooks Air Force Base, TX 78235-5301

This is a Department of Defense computer system for authorized use only. DoD computer systems may be monitored for all lawful purposes, including to ensure that their use is authorized, for management of the system, to facilitate against unauthorized access, and to verify security procedures, survivability, and operational security. Using this system constitutes consent to monitoring. All information, including personal information, placed on or sent over this system may be obtained during monitoring. Unauthorized use could result in criminal prosecution.

POC: AFRL/HEDM, (210)536-6816, DSN 240-6816