Copyright © 2010 USS PUEBLO Veteran's Association. All rights reserved.

The Pueblo,

By James (Scotty) Reston

Who Is To Judge The Judges?

Secretary of the Navy Chafee says the Pueblo Case is "closed," but an

interesting philosophic question remains. Who is to judge the judges?

The men who make decisions about war and the men who carry them

out live by different rules. The first volunteer for political office and

most of the second are drafted to fight, and both, being human, make

mistakes; but the fighters must answer for their missions and the men

who ordered the missions do not have to answer and even sit in

judgment on their men.

It is easy to understand why the senior officers of the Navy recommended a court-martial for Comdr. Lloyd M. Bucher. He broke the Navy's tradition of going down with the ship, and tradition is important. It is also easy to understand why Secretary Chafee rejected the court-martial, for the Pueblo was not only a naval and political disaster, but a rebuke to the United States as well-as to Commander Bucher. And Secretary Chafee clearly wanted to bury it as soon as possible.

Any reasonable man would have done the same thing, but after the legal and political problems of the Pueblo are over, everybody is still vaguely uneasy. It is out of the headlines but not out of sensitive minds. For Commander Bucher, while he may have been a weak and blundering captain, has become a symbol of the helpless individual directed and even humiliated by the judgments and power of the state and this is almost the central conflict in our society today.

THE 303 COMMITTEE

Consider, for example, the 303 Committee in Washington, which very few people, and probably not even Commander Bucher, have ever heard of, even now. This is the committee charged with approving intelligence missions all over the world, such as the Pueblo mission off the North Korean coast. It is composed of the Deputy Secretary of Defense, the Under Secretary of State, the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency and the Presidential Assistant for National Security Affairs in the White House, among others. These are human beings, too, subject to human error. They have primary responsibility for recommending these spy missions. They are above even the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the commanders in the Pacific, let alone Commander Bucher or his superior officers in Japan.

They approved the Pueblo mission. They made the judgment that even a spy ship outside territorial waters would not be attacked, or at least that the advantage of the spy mission was greater than the risk. In the perspective of history, it was not an unreasonable recommendation to the President, but it proved to be wrong-and was even repeated by the 303 Committee (*1) and by the president after the Pueblo incident when they approved sending an unguarded spy-plane into the same area, only to have it shot down.

All made mistakes of judgment, but only Commander Bucher was held accountable and put through a medieval trial which exposed his agony and broke his spirit. Maybe he was unfit for command. Maybe this orphan boy, pushed beyond his capacities, was too weak to be strong enough to risk the resentment of his crew. But other men chose him for command and pushed him into a situation beyond his capacities and they are invisible, unidentified and uncharged.

KENNEDY'S REFLECTION

"Life is unfair," President Kennedy said, and this is the only point of the story. The misjudgments in the Pueblo incident were general. No one man was to blame, but everybody was to blame, and only Commander Bucher was blamed in the end.

"A time will come," H. G. Wells wrote many long years ago, "when a politician who has willfully made war and promoted international dissension will be as sure of the dock and much surer of the noose than a private homicide. It is not reasonable that those who gamble with men's lives should not stake their own."

It is a hard philosophy and one wonders whether it will ever come true. But the Pueblo Case dramatizes the inequality between the men who give the military orders and the, men who have to carry them out. There were politicians and naval officers who tried to prove that all would have been well if only Bucher had carried out the old tradition, and gone down with his men and his ship, but he defied the tradition and has now taken his rebuke.

It is the old Billy Budd dilemma of duty and conviction all over again. The individual

has been punished and the institution has been spared. Secretary Chafee tried to soften

the tragedy by saying: "They have suffered enough and further punishment would not

be justified," so the novelists and dramatists will have to take it from here.

Notes:

1. The 303 Committee was an interdepartmental committee that reviewed and authorized covert operations. Established under NSC 5412/2, December 28, 1955, it was known as the Special Group or 5412 Committee until National Security Action Memorandum No. 303, June 2, 1964, changed its name to the 303 Committee. In 1964-1968, it consisted of the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, the Deputy Secretary of Defense, the Deputy Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, and the Director of Central Intelligence

By James (Scotty) Reston

Who Is To Judge The Judges?

Secretary of the Navy Chafee says the Pueblo Case is "closed," but an

interesting philosophic question remains. Who is to judge the judges?

The men who make decisions about war and the men who carry them

out live by different rules. The first volunteer for political office and

most of the second are drafted to fight, and both, being human, make

mistakes; but the fighters must answer for their missions and the men

who ordered the missions do not have to answer and even sit in

judgment on their men.

It is easy to understand why the senior officers of the Navy recommended a court-martial for Comdr. Lloyd M. Bucher. He broke the Navy's tradition of going down with the ship, and tradition is important. It is also easy to understand why Secretary Chafee rejected the court-martial, for the Pueblo was not only a naval and political disaster, but a rebuke to the United States as well-as to Commander Bucher. And Secretary Chafee clearly wanted to bury it as soon as possible.

Any reasonable man would have done the same thing, but after the legal and political problems of the Pueblo are over, everybody is still vaguely uneasy. It is out of the headlines but not out of sensitive minds. For Commander Bucher, while he may have been a weak and blundering captain, has become a symbol of the helpless individual directed and even humiliated by the judgments and power of the state and this is almost the central conflict in our society today.

THE 303 COMMITTEE

Consider, for example, the 303 Committee in Washington, which very few people, and probably not even Commander Bucher, have ever heard of, even now. This is the committee charged with approving intelligence missions all over the world, such as the Pueblo mission off the North Korean coast. It is composed of the Deputy Secretary of Defense, the Under Secretary of State, the Director of the Central Intelligence Agency and the Presidential Assistant for National Security Affairs in the White House, among others. These are human beings, too, subject to human error. They have primary responsibility for recommending these spy missions. They are above even the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the commanders in the Pacific, let alone Commander Bucher or his superior officers in Japan.

They approved the Pueblo mission. They made the judgment that even a spy ship outside territorial waters would not be attacked, or at least that the advantage of the spy mission was greater than the risk. In the perspective of history, it was not an unreasonable recommendation to the President, but it proved to be wrong-and was even repeated by the 303 Committee (*1) and by the president after the Pueblo incident when they approved sending an unguarded spy-plane into the same area, only to have it shot down.

All made mistakes of judgment, but only Commander Bucher was held accountable and put through a medieval trial which exposed his agony and broke his spirit. Maybe he was unfit for command. Maybe this orphan boy, pushed beyond his capacities, was too weak to be strong enough to risk the resentment of his crew. But other men chose him for command and pushed him into a situation beyond his capacities and they are invisible, unidentified and uncharged.

KENNEDY'S REFLECTION

"Life is unfair," President Kennedy said, and this is the only point of the story. The misjudgments in the Pueblo incident were general. No one man was to blame, but everybody was to blame, and only Commander Bucher was blamed in the end.

"A time will come," H. G. Wells wrote many long years ago, "when a politician who has willfully made war and promoted international dissension will be as sure of the dock and much surer of the noose than a private homicide. It is not reasonable that those who gamble with men's lives should not stake their own."

It is a hard philosophy and one wonders whether it will ever come true. But the Pueblo Case dramatizes the inequality between the men who give the military orders and the, men who have to carry them out. There were politicians and naval officers who tried to prove that all would have been well if only Bucher had carried out the old tradition, and gone down with his men and his ship, but he defied the tradition and has now taken his rebuke.

It is the old Billy Budd dilemma of duty and conviction all over again. The individual

has been punished and the institution has been spared. Secretary Chafee tried to soften

the tragedy by saying: "They have suffered enough and further punishment would not

be justified," so the novelists and dramatists will have to take it from here.

Notes:

1. The 303 Committee was an interdepartmental committee that reviewed and authorized covert operations. Established under NSC 5412/2, December 28, 1955, it was known as the Special Group or 5412 Committee until National Security Action Memorandum No. 303, June 2, 1964, changed its name to the 303 Committee. In 1964-1968, it consisted of the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, the Deputy Secretary of Defense, the Deputy Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, and the Director of Central Intelligence

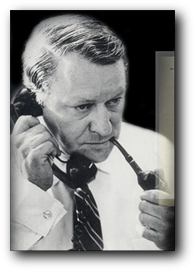

James "Scotty" Reston

James Barrett Reston (1909-1995), born in Scotland, raised in Ohio, educated in Illinois, spent most of his life in the nation's capital. It was there, in the period between the end of World War II and the end of the war in Vietnam, that he became the preeminent journalist of his generation. The place and time were important to Reston's influence and success. His career roughly coincided with the Cold War, when decisions made in Washington were central to the very survival of the United States of America.

(University Archives, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)

(University Archives, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign)