The Hi-jacking

By Skip Schumacher

Operations Officer USS PUEBLO

One was killed; four were seriously injured; nine others were incapacitated.

The Pueblo "Incident" often overlooks the brutality with which the North Koreans changed the Cold War cat-and-mouse game of intelligence collection. Collectively, our military had grown complacent about the rules: push and counter-push, cajole and threaten but ultimately one side "blinks" and the game is over. Whether in the air, on the sea, or lurking in the dark corners of some third-world client country, there was an honor amongst those struggling at the margin. The game wasnít about victory; it was about intelligence data gathering, filling up the blank pages in everyoneís order of battle. Know their enemy, know his limits, and know how far he can be pushed. A game of courage and fortitude, but also judgment and wisdom and years of accumulated experience.

The North Koreans blew all of that away with their opening salvo. It wasnít a shot across the bow, or rockets screaming low across the waves. It was virtually point-blank and aimed at the pilothouse itself - the very nerve center of the command and control infrastructure of the ship. That first set of shots knocked out all of the pilothouse glass; at least one of our major antennas and caused minor if rather startling injury to many crewmen. And, it changed the rules of the game forever.

Even more, it revealed in a flash the very defenseless nature of the ship, its mission, its backup and its entire conception. With that opening shot the PUEBLOís main line of defense, the time-honored respect of the freedom of the seas, was blown away. What was left was an undefended ship with no hope of either thwarting the intentions of its hijackers or escaping to the open sea.

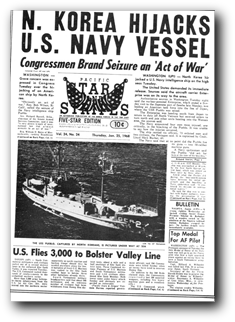

The PUEBLO had no armor protection whatsoever; its armaments consisted of 10 Browning semi-automatic rifles, a hand-full of .45 caliber pistols and two .50 caliber machine guns wrapped in frozen tarps on the starboard and aft rails. With these tools it was asked to fend off 4 torpedo boats, 2 submarine chasers and MiG jet aircraft. Not very good odds.

Captain Bucherís strategy was to stall for time. Time was his friend; time for the might of our military to be brought to bear; time for the crew to complete emergency destruction; time for the North Koreans to realize the foolishness of their brazen attempt to seize a U.S. Navy warship on the high seas. So time is what he sought, anyway he could.

The North Korean strategy, on the other hand, was to corral the ship closer into its own territorial waters and then board it and take possession of the ship, its crew and all of its contents. Time, too, worked against them since they knew (as did we) that our military might would arrive and that possession and control of the ship was absolutely essential. So each side had its strategy and fought to the best of its ability over that most precious of commodities: time itself.

For Bucher, of course, this meant heading for the open sea at full power. This meant 12 knots, not a speed that would allow much distancing, but a factor, never the less, since every mile he could gain to the east meant that much more time needed for the North Koreans to get the ship into port. So he maneuvered as best he could to keep the ship headed towards the open sea.

The North Koreans, of course, had the guns and the willingness to use them. Which they did, time and again. Heading to sea meant we would have to sail right into their guns and salvos, forcing us to protect life by turning. Likewise, slowing down caused them to encourage us to speed up. Finally, as they became wise to our strategy they focused on outward signs of our destruction efforts, and directed their gunfire towards those locations.

The death and serious injuries came as a result of our efforts to destroy publications and materials. And, there was no protection. The outward skin of the ship was aluminum, offering no protection at all. Machine gun bullets made small holes in the shipís exterior, and the 57mmís cut through that skin with impunity and did their damage.

Ultimately, Commander Bucherís choices were denied to him one by one. No running for the open sea, no dawdling on the trip toward Wonsan, and watch out for any signs of attempted material destruction. Add to that the loss of one man and the injuries to so many others and his choices evaporated before him.

The death and destruction to the personnel of the ship donít sound terribly severe - maybe 18 injured one way or another (although 22 Purple Hearts were awarded for injuries during the day of capture). But that was 20% of the shipís compliment, equivalent to about 1,000 men on an aircraft carrier.

The battle over time also swung heavily on the response the United States was going to take. South Korea was armed to the teeth; our Fifth Air Force was headquartered in Okinawa; Japan was home base to several squadrons; the USS Enterprise was in the Sea of Japan.

For the North Koreans, then, the clock was running out and they needed to seize the ship in a hurry, before the expected response came along. For the PUEBLO, on the other hand, the silence from our shore-based commanders was deafening. Despite excellent on-line fully encrypted teletype-based resources and prepared reports from PUEBLO, absolutely no instructions were ever received.

And so the PUEBLO was, ultimately, alone, with one dead and many injured crewmen, no indication of support or assistance, and an enemy bent on our destruction and able to inflict his will without restraint. And so the final boarding attempt was successful and the ship was boarded, seized and hi-jacked.

By Skip Schumacher

Operations Officer USS PUEBLO

One was killed; four were seriously injured; nine others were incapacitated.

The Pueblo "Incident" often overlooks the brutality with which the North Koreans changed the Cold War cat-and-mouse game of intelligence collection. Collectively, our military had grown complacent about the rules: push and counter-push, cajole and threaten but ultimately one side "blinks" and the game is over. Whether in the air, on the sea, or lurking in the dark corners of some third-world client country, there was an honor amongst those struggling at the margin. The game wasnít about victory; it was about intelligence data gathering, filling up the blank pages in everyoneís order of battle. Know their enemy, know his limits, and know how far he can be pushed. A game of courage and fortitude, but also judgment and wisdom and years of accumulated experience.

The North Koreans blew all of that away with their opening salvo. It wasnít a shot across the bow, or rockets screaming low across the waves. It was virtually point-blank and aimed at the pilothouse itself - the very nerve center of the command and control infrastructure of the ship. That first set of shots knocked out all of the pilothouse glass; at least one of our major antennas and caused minor if rather startling injury to many crewmen. And, it changed the rules of the game forever.

Even more, it revealed in a flash the very defenseless nature of the ship, its mission, its backup and its entire conception. With that opening shot the PUEBLOís main line of defense, the time-honored respect of the freedom of the seas, was blown away. What was left was an undefended ship with no hope of either thwarting the intentions of its hijackers or escaping to the open sea.

The PUEBLO had no armor protection whatsoever; its armaments consisted of 10 Browning semi-automatic rifles, a hand-full of .45 caliber pistols and two .50 caliber machine guns wrapped in frozen tarps on the starboard and aft rails. With these tools it was asked to fend off 4 torpedo boats, 2 submarine chasers and MiG jet aircraft. Not very good odds.

Captain Bucherís strategy was to stall for time. Time was his friend; time for the might of our military to be brought to bear; time for the crew to complete emergency destruction; time for the North Koreans to realize the foolishness of their brazen attempt to seize a U.S. Navy warship on the high seas. So time is what he sought, anyway he could.

The North Korean strategy, on the other hand, was to corral the ship closer into its own territorial waters and then board it and take possession of the ship, its crew and all of its contents. Time, too, worked against them since they knew (as did we) that our military might would arrive and that possession and control of the ship was absolutely essential. So each side had its strategy and fought to the best of its ability over that most precious of commodities: time itself.

For Bucher, of course, this meant heading for the open sea at full power. This meant 12 knots, not a speed that would allow much distancing, but a factor, never the less, since every mile he could gain to the east meant that much more time needed for the North Koreans to get the ship into port. So he maneuvered as best he could to keep the ship headed towards the open sea.

The North Koreans, of course, had the guns and the willingness to use them. Which they did, time and again. Heading to sea meant we would have to sail right into their guns and salvos, forcing us to protect life by turning. Likewise, slowing down caused them to encourage us to speed up. Finally, as they became wise to our strategy they focused on outward signs of our destruction efforts, and directed their gunfire towards those locations.

The death and serious injuries came as a result of our efforts to destroy publications and materials. And, there was no protection. The outward skin of the ship was aluminum, offering no protection at all. Machine gun bullets made small holes in the shipís exterior, and the 57mmís cut through that skin with impunity and did their damage.

Ultimately, Commander Bucherís choices were denied to him one by one. No running for the open sea, no dawdling on the trip toward Wonsan, and watch out for any signs of attempted material destruction. Add to that the loss of one man and the injuries to so many others and his choices evaporated before him.

The death and destruction to the personnel of the ship donít sound terribly severe - maybe 18 injured one way or another (although 22 Purple Hearts were awarded for injuries during the day of capture). But that was 20% of the shipís compliment, equivalent to about 1,000 men on an aircraft carrier.

The battle over time also swung heavily on the response the United States was going to take. South Korea was armed to the teeth; our Fifth Air Force was headquartered in Okinawa; Japan was home base to several squadrons; the USS Enterprise was in the Sea of Japan.

For the North Koreans, then, the clock was running out and they needed to seize the ship in a hurry, before the expected response came along. For the PUEBLO, on the other hand, the silence from our shore-based commanders was deafening. Despite excellent on-line fully encrypted teletype-based resources and prepared reports from PUEBLO, absolutely no instructions were ever received.

And so the PUEBLO was, ultimately, alone, with one dead and many injured crewmen, no indication of support or assistance, and an enemy bent on our destruction and able to inflict his will without restraint. And so the final boarding attempt was successful and the ship was boarded, seized and hi-jacked.

the PUEBLO Incident

50 Cal. machine gun on

PUEBLO in Pyongyang, NK

(note: lack of canvas tarp

or crew protection)

(2000 tourist photo in NK)

PUEBLO in Pyongyang, NK

(note: lack of canvas tarp

or crew protection)

(2000 tourist photo in NK)

Copyright © 2018 USS PUEBLO Veteran's Association. All rights reserved.

North Korean propaganda film opening title